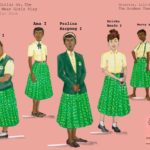

Plaid green skirts or green dresses? Sandals or Mary Jane flats? Glamorous ball gowns or Ankara print dresses? The specific costume pieces may vary, but the overall style remained remarkably consistent across three recent productions of School Girls; Or, the African Mean Girls Play.

Jocelyn Bioh’s frequently produced comedy, set in 1986, is about a group of schoolgirls in Ghana competing to represent their country in the Miss Universe Pageant. Bioh, inspired by both her and her mom’s experience in boarding school(her mother’s in Ghana) recreated the lives of teenage girls interested in fashion and pop music, particularly from the West. While remaining lighthearted and comedic, Bioh simultaneously addressed the issue of colorism that exists in the Black community and the role it plays in the lives of Black women and girls.

Each of the three costume designers used a different process, but research played a consistently crucial role in accurately representing African, as well as African-American culture.

Jarrod Barnes, a costume designer in Atlanta, designed the look of the production at True Colors Theatre Company. Coming from a fashionable family, Barnes spent time with them and their photo albums to capture the true essence of the 80’s. “My mom was a bit of a fashionista,” Barnes said. “My grandma was a seamstress, and I have a very fashionable father.” He also spent time soaking up information from his godmother about her trips and time spent in West Africa. School Girls ran at True Colors from February 11 to March 8.

In the play, the girls’ pageant dresses come from the new girl at the school, Ericka, who recently arrived from America. Barnes combined his own memories of 1986 with family photos from that period to create the pageant looks. He spoke with African women at shops in Atlanta, and researched Ghana to learn more about how teenage girls there dressed in the 1980s.

“To make sure I have a certain level of accuracy, I cross-reference my designs and my visions to images from the actual time period,” Barnes said. He also makes sure every color complements the actors’ complexions while adding dimension and zest to the play’s rather subdued setting of the school cafeteria. In Ghana, the uniforms are mostly green and yellow; to tone this down, Barnes chose an emerald green with a white shirt.

For Barnes, one challenge of costume designers can be having a different vision from the director. “A lot of times as designers, we can see it but sometimes we have to sell it to the director,” Barnes said. “It’s not their wheelhouse to study the fashion history, to know exactly what was going on at a particular time period or what type of shoes this particular person wore. That’s where we come into play, to bring the details.” His advice? “Stand your ground but have flexibility.”

The use of Ankara print fabric posed one such challenge on this production. Barnes said it meant a lot to have some of it present in the play, which was a different vision from the Tinashe Kajese-Bolden, the play’s director. After settling on an Ankara print necktie to add a subtle touch to the look of the uniform, he carefully researched to find the right print to represent Ghana. “A lot of times, people think, ‘Oh, it’s an African print,’ but each country has a print common to them. There are some that are distinctively from Ghana, distinctively Zimbabwe, distinctively Kenya.”

Barnes said he found it crucial to create an accurate depiction of the Ghanaian schoolgirls. “I never know if people from Ghana are going to come to that show,” he said, “and if they do, I don’t want them to walk out because I offended them.” He also used his designs to fight a misconception that he says exists in the theatre world: “So many shows I’ve had to design, the image they want to provide of us is just so subpar to who we are as a people. I fuss and I fight all the time for this misconception that we as African-Americans, if we’re poor, we look bad. I don’t know that to be true.”

Karen Perry found herself fighting these same misconceptions over her School Girls designs for Berkeley Repertory Theatre, who had to cancel their live production set to run from March 19 to May 3 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. She said she grew slightly annoyed at some of the assumptions being made about the characters. “Most of my design career has been trying to explain who Black people really are when we leave our home,” Perry said. She was taught that clothes should not tell your story. “My grandmother would say, ‘No one needs to know what’s in your house.’”

She also faced the assumption that because this was a story set in Africa, everyone would wear Kente cloth. Perry, set on showing that black people are more than one’s personal perception, went with an emerald green dress with elbow-length sleeves for the uniform, topped with a black vest embroidered with the school emblem on the chest. She studied the way Ghanaian girls dressed from head to toe, capturing the short afros and school shoes. For the pageant dresses, Perry got to play with the looks of Whitney Houston and Madonna. “That’s the fun part of the play because they all get to wear their best ’80s dress,” she said.

As a student at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York City, Perry said, she was constantly told that her designs were too costume-y. Her draping teacher once rudely suggested she stand in the alley of a Broadway theatre and get a costume designer to teach her because she was never going to be a fashion designer. “He didn’t realize that even in his sarcasm, I was like, ‘Oh, finally, a clue,’” she said. A few weeks later, Perry and some FIT friends put on a fashion show that helped her find work with a Black costume designer from Carnegie Mellon University, who taught her about building sets and creating costumes.

For Schoolgirls, Perry went back to her fashion roots to create the look of the show. She shopped at vintage clothing stores in search of ’80s looks, then recreated new dresses from what she found. “I started taking them apart, cutting them up, adding legs, and putting on rhinestones and beads,” she said. “Those dresses got completely redone and re-embellished.” She turned gowns into mini-dresses and added backs to strapless dresses, personalizing each one to match their character.

Sometimes she found a great dress but couldn’t make it fit perfectly without taking it completely apart. Other dresses had to be dyed and hemmed. One particular challenge was the look of Eloise, the pageant recruiter. Perry created her three outfits in the image of Jackée Harry, but it took nine different outfits to create a look that balanced her westernized style with those of West Africa.

For Samantha Jones at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago, the main challenge was finding the exact information she was looking for online. So she said she went off what she found and knew to be true. Jones chose a green and yellow plaid skirt for the uniforms, and paired them with cream-colored button-down shirts. She then individualized each girl with accessories: a headband here, a vest there.

“There’s a largely theoretical portion of my job that is often adjusted for the reality of who I end up working with,” Jones said. She spent time talking to the cast, and drew inspiration from the ’80s icons that sparked her love for fashion: Flo Jo, African American Barbie dolls in the 80’s, and Diahann Carroll. Her guide was always what a 16-year-old at the time who wanted to feel like a glamorous adult would wear. “It’s a lot of ’80s black-girl fantasy in terms of the clothes,” she said.

One thing that set Jones’s designs apart was her use of Ankara fabrics. While Barnes and Perry used small touches of the African prints or confined them to the school headmistress, Jones constructed two complete Ankara dresses, in addition to the headmistress’s outfit.

Because of Jones’s rapport with the director, Lili-Anne Brown, she had complete control of how the play would look.

“There’s a trust level,” said Brown. “I tend to be really, really specific with costume designers, except for Samantha, who I’m just like, whatever, I know I’m going to love it. I trust her so much and she really knows what she’s doing.” In addition to having a great working relationship, Brown and Jones both envisioned the same look for the play. Brown said she wanted to see traces of Cydni Lauper and Whitney Houston and she knew Jones could deliver.

Although Jones was familiar with the style of the ’80s, she was still entering unfamiliar territory with the school uniforms. She said she wanted to be sensitive to a world she did not know and keep the designs very close to the look of Ghanaian school uniforms today. “There is a presumption that I’m gonna get this right,” she said. “I’m honoring the fact that I’m still an outside perspective looking in.”

Jones scored big with her pageant dresses. “One of my assistants hunted down all these dresses on Etsy. They turned out to be from the lady who supplies a bunch of the fun, poppy, sparkly dresses from Glow on Netflix–that ’80s kind of fantasy. I was like, ‘Oh, yeah, give me all of those.’”

Gracyn Doctor is a Goldring Arts Journalism graduate student at Syracuse University.