Work on theatre sets across the country has come to a shutdown-induced halt, many half-finished projects left to languish in production shops. That does not mean their creators have been idle. A kind man in a cardigan once reminded the world to “look for the helpers,” and during the coronavirus pandemic, there is no shortage of helpers to look for. Theatre staff across the country have volunteered by sewing fabric masks for their communities, and some have turned up the technology by fabricating personal protective equipment (PPE) using 3D printers and computer numerical control (CNC) machines to produce protective shields for health care workers.

“I think that a lot of us in the stagehand and technical theatre world very much enjoy solving strange problems—learning new skills and new materials and new ways to use things,” said Joel Morain, carpenter and A/V coordinator at Glimmerglass Festival. “So adapting materials and adapting techniques for non-standard uses is what stage crews are purpose-built to do.”

There is a certain symbiotic relationship between the Glimmerglass Festival in Cooperstown, N.Y., and the nearby Bassett Medical Center. Both are teaching facilities, and many interns from the festival’s production shop have kept the medical staff at Bassett busy. “You know, we wish we didn’t compare as many notes as we do,” said Morain. “But we do send a lot of kids there during the course of the summer for little cuts and scrapes and bruises and needle pierces and things like that. So it’s nice that we can help them out and pay them back a little.”

When Glimmerglass cancelled its 2020 season, Morain began to focus on helping others, first by making birdhouse building kits for local schoolkids and then by manufacturing plastic intubation boxes for medical workers. These boxes create a protective barrier around the shoulders and head of a patient that allows medical staff to insert breathing tubes into patients while minimizing exposure to COVID-19. Morain first learned about the boxes from his wife, Abby Rodd, director of production at Glimmerglass. Using info from a website she found, detailing what intubation boxes are and how to make them, and some scrap plastic from the Glimmerglass prop shop, Morain created five boxes which he donated to the nearby medical center.

Morain thought this was as far as the project would go for him, until he learned that designer/builder Todd Thomsen in nearby Hamilton, N.Y., was raising funds for a similar initiative. The two began constructing these plastic boxes together, and Thomsen worked to obtain the needed plastic from sources across the country. Using feedback from medical professionals, the two modified the initial designs to better adapt to medical staff’s needs so that the boxes would nest within one another for more efficient shipping. Morain used his CNC machine, a very precise computer-controlled milling machine, in his home shop to cut out the plastic sections, which were then chemically welded using a solvent adhesive.

Dr. James T. Dalton, director of medical education at Bassett, said the facility didn’t have any devices like this prior to Morain’s donation. An ER doctor provided some feedback on the model to Dalton after receiving the first one, which Dalton then passed along to Morain, who, according to Dalton, was quickly back with four new models in about 24 hours. Dalton, who considers himself a friend of the Glimmerglass Festival and many of its staff, was touched by Morain’s efforts. “Doctors, nurses, and health care workers are getting a lot of press these days for being heroes, and it is deserved,” he said. “But the people in communities who see a need and meet that need—without question or delay, and without any expectation of reward or recognition—they are every bit as much heroes.”

Similarly, when Cleveland State University in Ohio closed its physical campus, technical director and instructor Cameron Michalak saw an opportunity to put his skills and innovation to use. The students in Michalak’s scenic construction classes work on the sets for the Theatre and Dance Department’s productions, and in March they had just struck one set and were in the early stages of preparing Dominique Morisseau’s play Blood at the Root.

“We were incorporating some really interesting sort of thermoforming-like vacuform techniques,” said Michalak. “So my brain was on plastic molding going into spring break, because that’s what we were about to start doing with the students. I think that my brain just could never get out of that gear.”

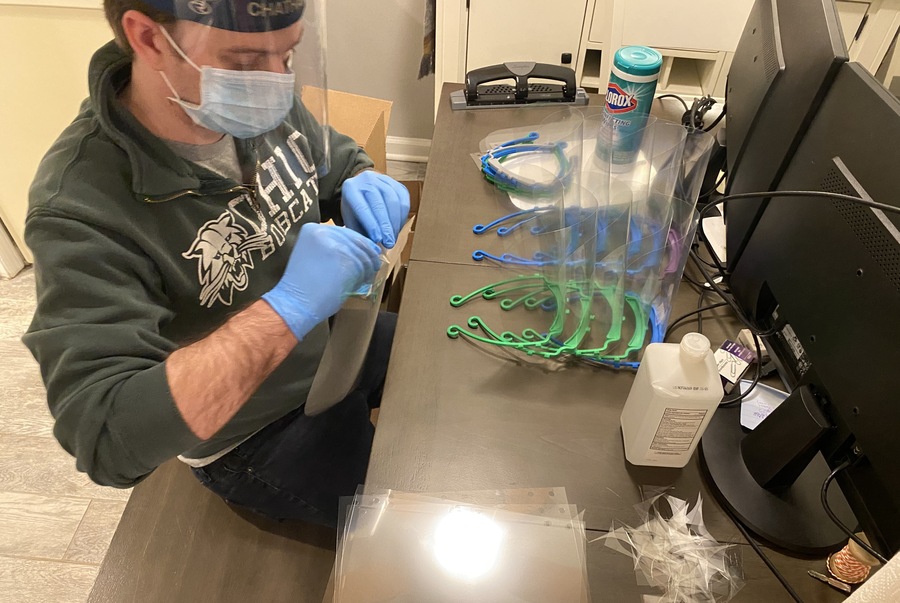

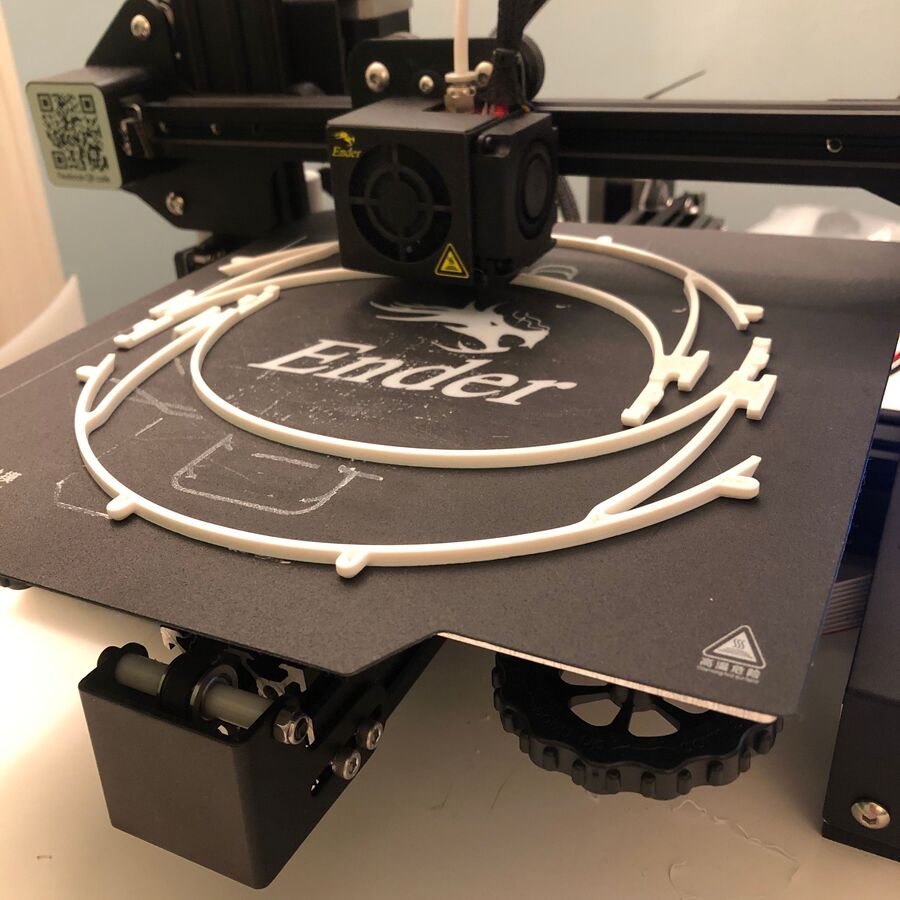

So when the campus closed and classes went online, Michalak began asking himself what he could do to help. He said it was around then that a friend who worked in health care sent him a post from a nearby medical facility that was requesting help from those with access to 3D printers. He reached out, and they sent him a link for the shields they needed, and Michalak began producing 3D printed face shield holders—and making the accompanying plastic shields—for the local health care workers.

The three 3D printers Michalak is using were donated for these efforts by his school. He got permission from Allyson L. Robichaud, Cleveland State University’s interim dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences, to bring the printers and supplies from campus home to his guest room, where he immediately began printing the shield holders and cutting plastic shields to go with them. To keep production going, Michalak ordered more spools of plastic for the printers, and as much plastic sheeting online as he could get.

“I was like, you know what, these materials are going to start to get really hard to find, because I’m sure everybody’s doing this,” Michalak said. “I was absolutely right. I ordered a whole bunch more of the plastic spools, and already shipping times were extending a lot further than normal.” He was able to obtain enough plastic sheets—which met the standards laid out in the link for the shields—to make 200 sets.

Christopher Young, general manager at Centenary Stage Company in Hackettstown, N.J., also found a focus for his energies through 3D printing face shield holders. “We were in the middle of so much” when the company closed its doors, Young said. “We had fortunately just finished a run of our spring show, which was The Sunshine Boys by Neil Simon. And then we were in the middle of rehearsals for our next show, so that was being constructed. It was all full steam ahead.”

Centenary Stage, a nonprofit theatre associated with Centenary University, had recently had two 3D printers donated to it by the university from a lab they were closing. After the pandemic shutdown, Young was contacted to be part of an initiative to 3D print face shields started by his brother, Jonathan Young, senior environment artist/production designer at WisEngineering LLC, who knew that Centenary Stage had just acquired these printers. Jonathan had worked with his brother in the past, helping to 3D print a demonic axe head for a production of Qui Nguyen’s She Kills Monsters.

“When he reached out,” Chris Young said, “I was like, ‘We’ve got these printers. I mean, they’re sitting here, we’re not doing anything with them.’” Chris then reached out to the university and was greenlit by Centenary Stage Company artistic director Carl Wallnau to transport the printers to his one-bedroom condo as part of this project. Since then, he said, this initiative has collectively distributed around 1,500 shields, most locally, though they did fill requests from out of state.

The face shields and intubation boxes were all donated to local medical centers, health care workers, and others in need. All three of these philanthropic craftsmen, who gave their time and expertise to creating these devices, worked with the support of their theatrical institutions. Young was able to take home and use the stock of printer spools, about 20 in total, from Centenary. Aside from the donation of the printers and materials from Cleveland State, Michalak said his dean had also made a financial donation that helped purchase some materials for the project. And in addition to the initial plastic used from the shop, Morain’s intubation boxes were highlighted in a recent Glimmerglass monthly newsletter.

Young says that since the end of April, he has seen a decrease in the requests for the face shields and has received fewer solicitations, though he is still happy to make and donate more shields for those in need. Morain has some facilities and maintenance projects at Glimmerglass slowly starting up as the shop reopens, but he has ideas for devices that can be scaled and fitted for ambulances or dental work. Michalak has shifted to printing “ear savers,” which are adapters for the ear loops that many fabric PPE masks have. Printing these by the bunch, he drops off boxes at local grocery stores and pharmacies.

“The first people we think about, obviously, were the hospital employees that are affected by this,” Michalak said. “But then there were places that never stopped working—the people who are feeding us and the people who are taking care of all of those essential things for us. And so it’s been really neat to just be able to help them out in some way.”

Sarah Tietje-Mietz is a Goldring Arts Journalism graduate student at Syracuse University.