The coronavirus pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on New York City. It has not only led the nation and the world in a number of fatalities but its economic impact in the city promises to be outsized. More than 1.2 million New York state residents filed for unemployment benefits over the course of the first month of the crisis. According to the The New York Times, New York City is projected to lose at least $7.4 billion in tax revenue by the middle of next year, a significant portion of which would have been generated by the performing arts: With a combined 1,737 playing weeks and attendance reaching 14.77 million, in the 2018-19 Broadway season productions grossed a total of $1.83 billion, beating the 2017-18 seasonal record of $1.7 billion by 7.8 percent.

There’s another disproportionate impact that COVID-19 is having: For troubling systemic reasons, it is devastating African Americans at much higher rates. Likewise in the theatre, where, despite a focus on Equity, Diversity & Inclusion, opportunities for artists of color were already heavily circumscribed, the shutdown threatens not only the precarious livelihood of artists of color but the health of institutions that have historically supported and nurtured them. It should come as no surprise that New York, the center of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and ’70s, has been a hotbed of theatre development shepherding the work of artists of color, in particular Black and Latinx artists. Among these institutions are the National Black Theatre (NBT), the Movement Theatre Company, INTAR Theatre, Nuyorican Poets Café, Teatro LATEA, QuickSilver Theatre Company, Blackboard Reading Series, Pregones/PRTT, Teatro SEA, Harlem Repertory Theater, Harlem9, and the Billie Holiday Theatre. Asian/Pacific Islander (API) playwrights have also seen their works developed at incubators like Leviathan Lab, the National Asian American Theatre Company (NAATCO), Ma-Yi Theater Company, the Pan Asian Repertory Theatre, Second Generation, and Noor Theatre, among others.

While many of these companies have had to fight for funding and recognition, their hard work has paid off: The combined efforts of these incubators over the last decade have fostered a creative parturition among their artist collectives, sowing the seeds of what many are calling a renaissance of works by POC artists—particularly Black talent—which have been a creative force, not only onstage, but on film and TV as well.

“I think the conversations that are being had, especially in the African American community, is that we understand and recognize—as we always have—that we are not a monolith, that we all have different experiences and points of view, and that they are worth being a part of the whole conversation of who we are,” notes dramaturg Shawn René Graham, literary director of the Classical Theatre of Harlem’s Future Classics Series and Playwright’s Playground, which shines a spotlight on the work of underrepresented writers. “But I do wonder if some of those tales that were told, if they were in residency at a Black space, how the conversation might be different or more robust…It’s the dramaturgy, and the lack of representation behind the scenes. I often wonder, with some plays, whose voices were in the room.”

Graham got her start as an intern at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles at a time when Oskar Eustis was the organization’s associate artistic director and theatre titans Tony Kushner, Eric Bogosian, and Anna Deavere Smith were developing works like Angels in America, Pounding Nails in the Floor With My Forehead, and Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992, respectively. Graham says she is still influenced by that time. In fact, some of her approach to running both reading series comes from watching the iconic comedy trio Culture Clash develop their work in front of live audiences. Boosting the profiles of emerging artists like Madhuri Shekar (House of Joy), Angelica Chéri (Berta, Berta), and Radha Blank (Netflix’s The 40-Year-Old Version), the Classical Theatre of Harlem (CTH) aims to uplift the next generation of artists as well as encourage “little Black boys, little Black girls, and little Black theys” living in Harlem to aspire to tell their own stories.

Graham arrived in 2011, when artistic director Ty Jones was “still rescuing the company from a significant amount of debt,” as she puts it. The only way to keep the theatre relevant then, when the company could not produce their usual number of mainstage productions, was to keep a reading series going. She was tasked with that project, along with helping make the festival an annual event and creating an annual holiday production. Now, with the COVID-19 shutdown, a similar barebones approach may come in handy. The company’s philosophy hasn’t changed, she says: “We are also hellbent on no barriers to access and being of service to the community that we serve, which is the Harlem community.”

Carpe diem has been a defining philosophy of the trifecta behind the rising little giant that is Liberation Theatre Company. Established in 2009, the Harlem-based theatre incubator has committed to the development of new Black playwrights, promoting the likes of James Anthony Tyler (Dolphins and Sharks), James Scruggs (3/Fifths), Dennis A. Allen II (The Mud Is Thicker in Mississippi), Liz Morgan (The Clark Doll), Camille Darby (Lords Resistance), Shawn Nabors (Cake), Deneen Reynolds-Knott (Baton), and Tylie Shider (Parable of the Backyard Roots). (Full disclosure: They have also developed my work as a playwright.) Spearheading the project are two founders, producing artistic director Sandra A. Daley-Sharif and associate artistic director Spencer Scott Barros, who are joined by associate producing director Bernard J. Tarver.

The trio is also part of the collaboration of Black theatre producers known as Harlem9, currently celebrating its 10th anniversary. Harlem9 won an Obie in 2014 for an annual 10-minute play festival, 48Hours in…Harlem, spawning various spinoff festivals around the country (Bronx, Detroit, Dallas, and Holy Ground, N.C.) and five published anthologies. Daley-Sharif and Barros, working actors who have been friends for 25 years, gush over Tarver and mention that he complemented their “old-school work ethic” when joining Liberation.

“We have a very similar intention and vision that we agree on,” Daley-Shariff says. Barros observes, “Even if we have a disagreement from an outside perspective, five seconds later we’ll let it go because we all want the same thing.”

This philosophy has bled into the gallimaufry of talent that the company has helped develop since their humble beginnings renting space at venues around the city. While small in scope, what the company lacks in resources, they make up for in discipline and tenacity. Such hard work led to collaborations with Off-Broadway theatres such as Playwrights Horizons to present an annual festival of new works when the duo were just starting out as producers.

“Sandra is a master at developing relationships with people that open all this space for us, like SPACE on Ryder Farm, like NBT, like National Dance Institute (NDI),” says Barros. “She meets people and people fall in love with her. But as far as space is concerned, that’s the biggest challenge for Black theatre companies in general. We don’t have space. We need a homebase, because we’re constantly in people’s space. We are constantly at their whims and desires from what they want from us, and sometimes it limits or puts perimeters around where we see the vision. And if we had it we could just do whatever the hell we wanted, but who can afford it?”

That’s why a core group of playwrights has tended to meet with the leadership trio in Daley-Sharif’s 2,500-square-foot apartment a few blocks north of Central Park North in Harlem. When the company was founded, Daley-Sharif says she wanted to create a company along the lines of LAByrinth in New York or Steppenwolf in Chicago—an artistic home for Black and brown talent to work and aspire to have a healthy work-life balance.

“I think that’s the difference between producing in your 20s and 30s, which we’ve done, and producing your 40s and 50s, which we are doing,” Barros says. “We’re more pragmatic and practical with what we’re doing. Reestablishing 11 years ago, we were very clear on what this was going to entail. It’s going to have to take focus, being very smart about where we get the money, how we find our talent. I think the benefit has been that we’ve worked with some of the greatest emerging talent in the city.” When they realized they would benefit from pooling resources and connecting with Black organizations and Black producers, that led to the creation of Harlem9, and ultimately an Obie.

Creating a space, says Daley-Sharif, where “Black and brown people can tell their stories in comfort…I think that’s huge!”

“That’s amazingly huge!” Barros adds. “I would say for most artists that work with us, this may be the only time where they have a singular experience where everybody in the room is like them.”

White organizations don’t necessarily “create that space and walk away and leave you alone,” Daley-Sharif points out. Some take that approach, she says, but there is a clear advantage to one run by folks who fully understand the Black experience. She adds, “Sometimes we do need to be policed, sometimes we do need to check ourselves—but I do think there is something to be said about being in a room where it is Black-led and where it’s comfortably facilitated.”

Daley-Sharif’s words call back to Lorraine Hansberry, author of the landmark family drama A Raisin in the Sun and the first Black woman and the youngest playwright to have a play performed on Broadway. Hansberry’s contributions extended past the proscenium and in her abbreviated career—she wrote her first play between her 26th and 27th birthdays—as she engaged with emerging artists of color and passed the baton.

In the years since her passing, the Black Arts Movement saw dramatists like Sonia Sanchez, Ossie Davis, Ishmael Reed, Amiri Baraka, and Ntozake Shange rise to prominence, each supporting one another. Theatre titan Charles Fuller (A Soldier’s Play) ushered in the post-Black Arts Movement, and August Wilson cemented it; and artists such as Anna Deavere Smith, Suzan-Lori Parks, Lynn Nottage, and Thomas Bradshaw followed suit. While the current generation of emerging playwrights pushes boundaries and takes the U.S. theatre field to task, many are mining inspiration from Hansberry’s contemporary James Baldwin, including cultural incubators like the Fire This Time Festival (TFTTF), named for Baldwin’s 1963 collection The Fire Next Time.

TFTTF began in 2009 with a weekend of performances of fully staged 10-minute plays by Kelley Girod, Derek McPhatter, Germono Toussaint, Pia Wilson, Radha Blank, Katori Hall, and Asiimwe Deborah/Deborah Asiimwe. The festival has become one of the most sought-after opportunities for young Black writers, with many of its writers achieving roaring success over the last decade: Dominique Morisseau (Pipeline), Antoinette Nwandu (Pass Over), Jocelyn Bioh (School Girls; Or, The African Mean Girls Play), Marcus Gardley (The House That Will Not Stand), Jordan E. Cooper (Ain’t No Mo’), Aziza Barnes (BLKS), C.A. Johnson (All the Natalie Portmans), Charly Evon Simpson (Behind the Sheet), Jonathan Payne (The Revolving Cycles Truly and Steadily Roll’d), Tanya Everett (A Dead Black Man), and Stacey Rose (America v. 2.1: The Sad Demise & Eventual Extinction of the American Negro).

“The theme of the first festival was: Is there a post-Black theatre, and if so, what are the stories?” says A.J. Muhammad, associate producer and director of TFTTF’s New Works Lab. Muhammad recalls that the inaugural fest took place in the early years of the Obama administration, when some believed the country had entered a post-racial era. That first season’s plays ranged from an Afro-futurism/sci-fi comedy by McPhatter to Girod’s pre-#MeToo era play about sexual harassment in higher education, Hall’s about skin bleaching across the African diaspora and South Asia, Toussaint’s about queerness in a Black church, and Pia Wilson’s existential piece about the past lives of two women. Recalls Muhammad, “All of the performances were sold out, and audiences were galvanized by what they saw, myself included.”

Girod, founder and executive producing director of the festival, testifies that when she graduated with a playwriting MFA from Columbia University, opportunities for emerging Black playwrights were scarce for her and her peers, who like her were trying to get their work produced by established New York theatre companies. Besides producing established Black playwrights, white mainstream theatre companies were limited in their scope of what they expected Black playwrights to write about, and Black playwrights were being pigeonholed. Not wanting to be held back by these gatekeepers and not content to wait for an invitation to the table, a new movement emerged. (New Black Fest at the Lark also emerged around this time.) The festival has been in residence with FRIGID NYC (formerly known as Horse Trade Theater Group) since its inception; FRIGID NYC is a nonprofit that presents a series of festivals throughout the year and other curated programming while managing two indie theatre spaces in downtown Manhattan’s East Village, the Kraine Theater and Under St. Marks.

“What Black theatre doesn’t have a shortage of is ingenuity, passion, determination, talent, generosity, resilience, tenacity, perseverance, and self-determination,” Muhammad says. Echoing others, he says that what Black theatre in New York suffers from is a lack of dedicated physical spaces, apart from such venues as National Black Theatre in Harlem or Black Spectrum Theater in Queens. “Like so many indie theatre companies and festivals, including the ones that are BIPOC, many of our companies are nomadic and there’s a crunch for physical space and resources.”

Muhammad expresses a need for alternative sources of funding, in addition to the those that support New York-area theatre, often predominantly white companies, such as the Ford, Axe-Houghton, and Shubert Foundations. “Are there Black-run philanthropic foundations that are comparable to the ones I mentioned?” Muhammad wonders. “There is Black wealth, but when it comes to our arts organizations, I don’t know if connections are being made between the Black philanthropies and our institutions.” Muhammad says he’d like to band together with other Black organizations and figure out how to cultivate relationships with Black philanthropists. “Those of us who are nonprofits may not have the same access to the white philanthropic foundations, or some of our organizations might be ineligible to apply for grants from those funders because of our small budget sizes or we don’t have a point of entry,” he says. “This is where the Black philanthropic foundations can come in to have that conversation with us.”

Government agencies unwittingly reinforce the inequity, Muhammad suggests. Tax-supported funding from the New York State Council on the Arts and the Department of Consumer Affairs, for instance, is frequently “earmarked for mainstream organizations in support of their diversity and education initiatives, which in many cases is their only point of contact with BIPOC artists.” He adds, “In the age of COVID-19, things might get more dire for all of us. This is also a time to think outside of the box in terms of funding sources and sustainability of our organizations.” In a time when no theatre can happen on any space and everything is virtual and “spaceless” due the pandemic, one of the many puzzles smaller theatre development incubators are having to figure out is how they might offer new opportunities to artists who are among the many that have been hit hardest by the pandemic and how to predict some of the extra challenges that may present themselves moving forward.

Incubators of color are hardly limited to the Big Apple. JAG Productions, in the small town of White River Junction, Vt., launched in 2016 with the mission to produce classic and contemporary Black theatre and serve as an incubator of new work that excites broad intellectual engagement. Most importantly, over the last couple of years, JAG has been responsible for taking Black and brown playwrights from NYC and workshopping their genre-bending theatrical works.

“At the confluence of the White and Connecticut Rivers, which separates Abenaki land into the majority-white states of Vermont and New Hampshire, JAG has nurtured and sustained a multigenerational and multiracial community with Black artists and community organizers at its center,” says the organization’s founder and producing artistic director, Jarvis Antonio Green, a queer director and actor from the South. “Serving as a vehicle for change, JAG has used theatre to catalyze community dialogue around critical issues of race, gender, sexuality, and identity and has played a central role in carving spaces for Black folks and people of color in the predominantly white town of White River Junction, Vt.”

Green describes his journey as “brutal,” with 10 to 15 years auditioning for roles on national tours and assisting directors, all of which led him to establish JAG. He traces its genesis to a call with a friend, Jonah Hankin-Rappaport, in which he explained how much he was struggling. Green says Hankin-Rappaoort responded, “Hey, I’m going to go up to Vermont. My girlfriend is finishing up school, and we’re gonna be working on this farm in Barnard called Fable Farm. Just come hang out for a summer.”

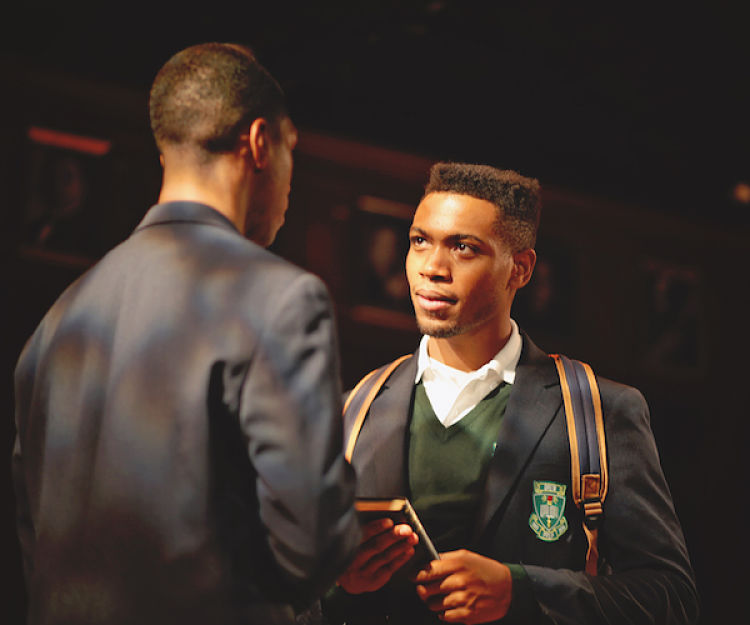

He fell in love with the rural town and eventually made it his home. Green says he saw the need for a company that would make Black, brown, queer, and transgender folks “more curious and aware of ourselves, make us more curious about where we’ve come from and what we’re into, and to access what is already there and to bring that out.” He also says he started the company to help people heal from harm caused by working in anti-Black cultural institutions. In its first season, the organization staged critically acclaimed productions of August Wilson’s Fences, Tarell Alvin McCraney’s Choir Boy, and Polkadots: The Cool Kids Musical, a youth-driven work inspired by the events of the Little Rock Nine. He also launched the company’s touchstone JAGfest, a multidisciplinary weekend-long festival of new works. Since its launch, more than 10,000 Upper Valley theatregoers and 1,200 students from 10 schools have attended JAG performances. In recognition of its work, JAG was honored by the New England Theater Conference (NETC) as the 2017 recipient of the Regional Award for Outstanding Achievement in American Theatre.

In October 2019, JAG’s fourth season opened with the world premiere of Nathan Yungerberg’s Afro-surrealistic family drama Esai’s Table and sent shockwaves through the Upper Valley community, inciting conversations about race and the value of Black life in America when it ran 15 performances at the Briggs Opera House. The production had further aspirations: Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, the play was slated to transfer Off-Broadway to the illustrious Cherry Lane Theatre. Postponed indefinitely, the New York run of Esai’s Table would mark a pivotal moment for JAG as its first world premiere, first Off-Broadway transfer, and first co-production. The blinding success in such a short period of time is uncanny, as the company operates in a state with an African American population of less than 2 percent.

Of course, the show’s postponement is just one example of the widespread devastation the epidemic has caused. “I think right now, in this time, in this moment, especially when there’s so much Black theatre and theatre about race, that it’s important to hold space for spirit and check in with people and how this work is affecting us and the emotions that could be triggering us,” Green says, recalling his time working alongside director Stevie Walker-Webb and in spaces like the Public Theater, where they’d circle up to touch base before every rehearsal and performance. “To hold that space for the people making the difficult art is important.”

As the country experiences a rude awakening in the time of COVID-19, these development incubators need to be more resilient and work almost entirely on deficit, sometimes sacrificing the commitment to making art in favor of fundraising and handling administrative duties. But the formidable contributions of artists of color to our theatre culture and literature have always been made against steep odds, and these institutions have been and will continue to be fighting for their rightful places on the stages, whenever they reopen.

Marcus Scott is a New York City-based playwright, musical writer, and journalist. He has contributed to Elle, Essence, Out, and Playbill, among other publications.