The curtains are closed, the seats empty, the stages deserted. The lifeblood of the theatre—the actors, directors, staff, and administrators—may have drained away for the time being. But these temples of entertainment still remain, lonely, yet not left alone.

Some of these historic theatres have been part of their communities for longer than the companies they house; others, like the 98-year-old Le Petit Théâtre du Vieux Carré in New Orleans, were built specifically for this purpose. Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused all theatres to close their doors. But while all performances have been put on hold, a supporting cast of management and staff still see to the well-being of these historic buildings, ensuring their survival through this time. Buildings, like people, become more delicate and more susceptible to damage and decay as they age, and leaving them unattended or unmaintained can place them at risk.

The Bangor Opera House’s 100-year history is filled with as many colorful stories and characters as the productions put on by its operating company, the Penobscot Theatre Company. Holding a place of prominence on Main Street in Bangor, Maine, this massive blond-brick building, tipped in simple white Art Deco details, is built on the foundations of the original 1889 opera house, which burned down in 1914. Old rum-running tunnels crisscross beneath the audience seating. Stage and screen siren Mae West once trod these boards, and local hero Stephen King has been spotted scribbling in the back rows.

Bari Newport, producing artistic director, has not been on-site since temporarily closing the theatre’s doors due to COVID-19, not just due to safety concerns but also, she says, because she finds it too difficult emotionally. The house’s usual staff of 15 has been cut in half, each working what she calls “extremely part time.” Newport speaks as protectively and proudly of the opera house, one of three buildings the Penobscot Theatre Company owns, as she does of the company itself. “It’s part of our identity, the theatre company’s identity,” she said. “It’s a big part of—and we’re a big part of—downtown Bangor.”

The building has no maintenance staff, even during regular operations; facilities and maintenance needs are met by a volunteer committee and theatre staff. Currently, she says, the company manager stops by twice a week to manage on-site issues and bring in the mail, while the production manager also checks in on the structure of the building each week.

A temporary closure of this nature has only occurred one other time in the history of Le Petit Théâtre du Vieux Carré’s building, when a series of financial issues closed its doors for more than six months in late 2010. The company, formed in 1916, built the “Little Theatre” in the historic French Quarter of New Orleans in 1922. Like the opera house, Le Petit, a deep terracotta-hued building with a bit of Spanish architectural flair, can also boast some ancient bones: One wall, according to Le Petit’s artistic director Max Williams, dates back to 1796, making it the second oldest in the quarter.

Similar to Penobscot, Le Petit does not have designated facilities or maintenance staff for its theatre, so it is up to production manager James Lanius to go through the building each week to make sure ongoing issues like water and moisture do not get to a critical point.

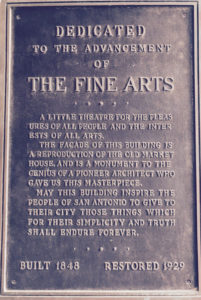

By contrast, George Green faced the mandatory shuttering of non-essential businesses proactively and with optimism in his role as CEO and artistic director of the Public Theater of San Antonio. Housed in the San Pedro Playhouse, located in one of the oldest municipal-built parks in the country, the theatre looks like a gleaming Greek temple to the muses. The company has one dedicated maintenance staff member cleaning and inspecting the 108-year-old neoclassical building each day.

The company made the decision to close its doors and cease production of Bright Star on March 15, a full 16 days before Texas Gov. Greg Abbott declared the closing of all non-essential businesses and activities. The now-empty building presents Green with opportunities for improvements that are usually not possible when the seats, stage, and dressing rooms are filled. In an effort to find meaningful work that to keep staff employed, Green found himself asking, “What are we allowed to do first?” He found his company able to move forward with having the green rooms and dressing rooms updated without going against the state’s coronavirus-related mandates or the preservation agreements around maintaining the historic character of the building.

The closures have lowered operating costs for many of these theatres, as needs like lighting systems, sound tech, and various supplies are unnecessary. This does not mean, however, that a giant master switch has been turned off, disconnecting the utilities and shutting down the building. HVAC systems still need to run, water and power are still required, and alarm systems need to be set at the ready.

Areas with warmer climates, like San Antonio and New Orleans, have climate-control issues specific to the heat, and, in the case of Le Petit, to the high humidity that comes with it. Le Petit’s primary current maintenance cost comes from running the HVAC continuously to combat the constant threat of mold and mildew. Sandbags have been left at the ready to contain flooding, which can occur seemingly in minutes during downpours. The company also pays monthly contracts with the adjoining restaurant company, which attends to larger issues like vandalism, while pest control company Ecolab makes sure the building doesn’t have any new and unwelcome tenants.

“The big thing is pests, you know,” said Le Petit artistic director Max Williams. “Making sure that rodents aren’t taking over the joint, basically. There’s not a huge problem, thank God, at least there hasn’t been with bugs. But the rats have taken over the French Quarter.”

Anchoring the corner of East Genesee and Irving Avenue in Syracuse, N.Y., just down the hill from Syracuse University (SU), is the decidedly newer Syracuse Stage building. The first of the Kallet Theatres built by movie-house magnate Myron Kallet in 1914, the understated Art Deco building was purchased by SU in 1958. Few vestiges of the original movie house remain, as the bulk of the building has gone through its share of nips, tucks, and updates. Syracuse Stage exists in the three-way overlap of professional theatre, university resource, and community asset. The health crisis has led to canceled shows, the decampment of the student body, and a vacancy where there had been vibrancy.

It is this last quality that Joseph Whelan, director of marketing and communications at Syracuse Stage, misses most.

“When we are in full swing with both Syracuse Stage and SU Drama, the amount of things going on in that building is just incredible,” Whelan said. “On any given weekend, let’s say mid-semester, you could have five different projects going on. There’s just so much activity, so much creativity happening in that building through the course of the year. It’s hard to think about it, in this time of the year, being empty.”

Both Syracuse Stage and the Public Theater of San Antonio find support from the larger organizations that own their buildings. While Syracuse Stage is its own nonprofit organization, SU maintenance and security staff attend to the building’s physical needs while Whelan and the rest of the Syracuse Stage staff work remotely. And while the Public maintains the interiors and all aspects of productions, the city of San Antonio cares for the exterior of the building, grounds, and parking lot.

“We’re lucky enough to have a great relationship with the city of San Antonio,“ Green said. “I think a lot of that is because of the service we provide to our community as artists. And secondly, we take really great care of that building. We love that building. It’s been our home our entire life.”

Before the rash of coronavirus-related closures, all of these theatres were in the throes of events, rehearsals, or full-scale productions. The ghost lights may be glowing now, and the dedicated staff reduced to a bare minimum. But they haven’t abandoned their posts. Instead they’re doing what it takes to make sure that once the coronavirus crisis is over, the house lights will turn on and your seat will be waiting for you.

Sarah Tietje-Mietz is a Goldring Arts Journalism graduate student at Syracuse University.