Taylor Mac first met Loretta Greco a decade ago over breakfast. Greco, who became artistic director of San Francisco’s Magic Theatre in 2008, and departs the company in May, invited Mac to her place for a home-cooked breakfast. Mac remembers the meeting as “an epic hang,” and says that Greco later told judy (Mac’s gender pronoun) that she knew she’d produce judy’s play when judy ate all her food. In her third season with Magic, Greco did produce Mac’s The Lily’s Revenge: A Flowergory Manifold, a five-hour play with 36 cast members and plenty of glitter, about a lily’s fight against nostalgia, among other things.

“She was the first artistic director to produce me full-out without asking me to raise the money,” says Mac. “It was a brave choice, and she’s continually made brave choices through her tenure.”

Greco’s 12-year run at Magic Theatre can be marked by the many relationships she’s built with playwrights. Mac feels lucky knowing that the support comes from the same company that nurtured Sam Shepard, the playwright in residence at Magic starting in 1975. Shepard’s decade-long tenure there included productions of Fool For Love, True West, and the Pulitzer-winning Buried Child. Several years after The Lily’s Revenge, Greco produced the world premiere of Mac’s Hir, a family drama about identity and gender, which judy wrote in response to Shepard’s Buried Child.

“Before critics came for opening night, she said, ‘What do you want to do next?’” judy recalls. “That’s the only time I’ve had that experience in any theatre in America. It’s what Joe Papp used to do, but nobody does that anymore. To have somebody say, ‘I’m in this with you for the journey, you’re not alone.’”

Seeing Mac’s work evolve has been a pleasure, Greco says. “It just seemed to me if you use the word home—and people bandy about this idea of artistic home—then it really had to be a home,” she says. “A home you can come back to at any time…One of the great joys of this job is watching and being able to support writers as they pivot. Because you don’t want them to do the same thing over and over again. Sometimes the pivots are really dramatic. Watching Taylor go from a 36-person, five-hour allegory to redreaming Buried Child is a big pivot.”

Another playwright Greco gave a home to is Mfoniso Udofia, the author of The Ufot Cycle, a series of nine plays that follow several generations of a family from Nigeria in America. Greco didn’t shy away from doing ones that were hard, Udofia says. An upstairs and a downstairs? A tree growing out of the floor? Not a problem. This support meant that other theatres took a chance on her work, says Udofia, who also acts and writes for television, including work on Netflix’s 13 Reasons Why and Apple TV’s Pachinko.

“One of the things I love best about Loretta is she’s the most non-risk-averse person I know,” she says. “She provided a home base, which is really important for a playwright. I can come and work on plays and see them through to production. That’s not something I take for granted. She’s one of biggest mouthpieces for my work and getting it out there—she was a champion for me.”

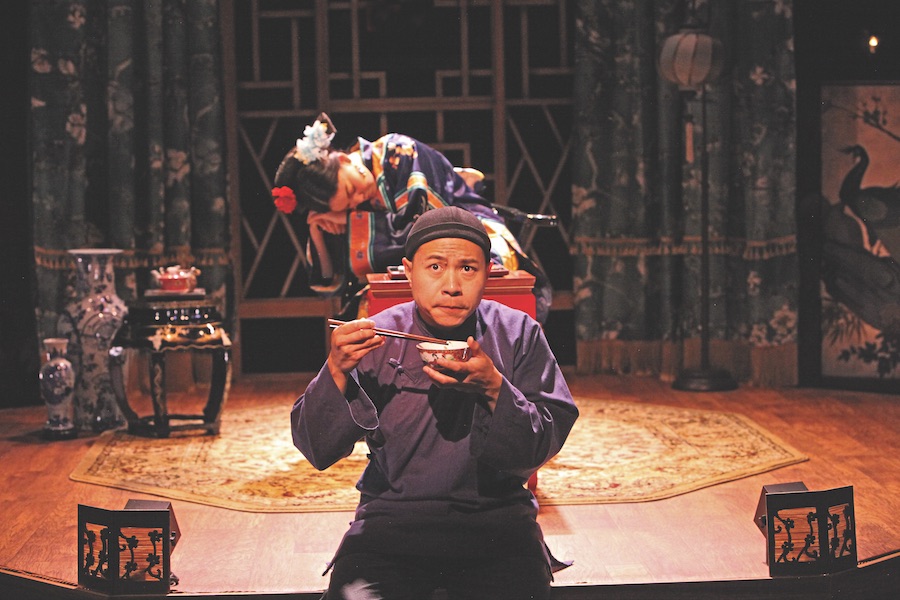

Magic’s connection with playwright Lloyd Suh spans Greco’s whole time at Magic—in her first season, she produced Suh’s American Hwangap, and she opened her last season with his The Chinese Lady. Another of his plays, Jesus in India, premiered at Magic in 2012. Suh, director of artistic programs at the Lark in New York City, says Greco has had a big impact on him both professionally and personally. “She’s a wonderful listener,” he says. “It’s very symbiotic how she creates the space for the writers she’s invested in to talk honestly and sincerely—where they are and what they want to do in a way that’s not transactional,” he says. “She talks about what she wants to do in the world, and that’s really gratifying on a personal level.”

(Photo by Jennifer Reiley)

Greco has expressed interest in his work beyond just what he does for Magic, Suh says. When he came to San Francisco to work on The Chinese Lady last fall, Greco set up appointments and made introductions for him to talk with people for a play he was working on for a different theatre. She insisted that he leave tech rehearsals to be sure to get his research done.

“Instead of me being helpful for the production at her theatre, she was being helpful for another production at a different theatre,” Suh says. “It’s another moment of her bewildering generosity.”

Luis Alfaro has written plays reimagining Greek tragedies in contemporary America, such as Oedipus Rex as Oedipus El Rey, where the title character is in prison, or Medea as Bruja, an immigrant in San Francisco’s Mission District. Alfaro says he long wanted to have his work at Magic, which he calls “the house that Sam built.” Everyone there gets involved on different levels, he says. He remembers calling up subscribers after Oedipus premiered at Magic last summer to ask them to come back for another season, and handing out fliers for Bruja at a poetry slam in Oakland. He appreciates that under Greco’s leadership, things were stripped down to their essentials.

“It’s this lovely, joyful process that is very personal and plays to people’s strengths,” he says. “I’m all about the spiritual life of a place, and you’re creating in the same atmosphere where so many others have, and the work is in the walls. She adds as she goes along. You show up with your assumptions about how you make a play, and what I love is all we had was just the floor, and you just build from there.”

Greco’s support for people who want to be in theatre extends beyond the playwrights who come to Magic. When Tarell Alvin McCraney’s The Brothers Size was playing at Magic in 2010, an outdoor concert right next to the theatre meant the afternoon performance couldn’t go on because of noise levels. Greco was determined that the show would go on—somewhere. So she got people to help her (including teacher and actor Awele Makeba) and they found a place in just a few hours: the theatre at a community college in Oakland, Laney, about 10 miles from Magic. When they showed up there for the performance, more than 400 people, most of them not white, were lined up waiting, Greco says.

She describes the conversation after the play as “mind-blowing,” and she decided this needed to continue and expand. Sean San José, a co-founder of the theatre group Campo Santo, helped her set something up with Michael Torres, another Campo Santo co-founder, and chair of the theatre department at Laney College. Since then, every production at Magic offers a free performance at the community college, and the whole process of putting on a play is opened up to the students from the first reading of the play.

“You a have a group of students who all think they’re going to be actors, sitting around a table of professionals, learning about what a dramaturg does, what a stage manager does, what a writer does, what a director does,” explains Greco. “Then they come back for tech and they observe, they come for opening night and then we bring the show to Laney. There are dozens of professionals in the Bay right now that came through this Laney/Magic collaboration.”

This initiative showcases Greco’s commitment not just to those already involved with theatre, but to nurturing those who want to be, San José says.

“They’re next generation theatremakers, every one of them,” he says. “Another thing about Laney is, I believe in the aesthetics of taking away the fireworks of theatre and saying it’s just storytelling. You’ll respond and you can dig it, and it doesn’t take a fancy coat to get into a fancy building and do a fancy show. You can go anywhere and do the thing and the magic will happen.”

Greco says she has loved her time with Magic. Sam Shepard might be remembered as building the theatre, but Greco will be remembered for inviting everyone in. Greco had been aware of the theatre because of Shepard, who she calls “one of our greatest writers, period, the end,” and getting to work with him there was a highlight for her. He was constantly searching, she says, writing for six decades, from when he was a teenager to a few days before he died in 2017. Greco keeps some of his short stories by her favorite chair—his work is like a balm for her.

“I was a complete idiot when I first met him,” she recalls. “I was so nervous that I drove up Franklin the wrong way with Sam in the car. It was hilarious because he was calming me down, and I drive down Franklin every day. It wasn’t a new road for me—it was that I had my hero next to me.”

Greco has no immediate plans once she leaves Magic, besides knowing she wants to direct and produce. She recently directed Udofia’s runboyrun at New York Theatre Workshop, and she plans to direct Mac’s Calamity Jane at Magic in 2021. She would like to take a little bit of time to decide what she wants to do next. (Meanwhile, Magic Theatre is currently conducting a nationwide search for the next artistic director.)

“I have another big job in me for sure,” she says. “I wanted to give myself the space for something new, and if there’s no space, I think it’s hard for a new opportunity to come in.”

Mac thinks that any theatre would be lucky to work with Greco because of her vision and leadership. “It’s that rare director who knows how to talk about new plays,” judy says. “She can do anything—she can talk Method or Aristotelian structure—she’s extremely well-versed. It’s nice to have somebody at the helm who has that depth.”

Emily Wilson lives in San Francisco. She writes for radio, print, and the web, including Smithsonian.com, the Daily Beast, California Teacher magazine, Theatre Bay Area, 48 Hills, Hyperallergic, Latino USA, Women’s Media Center, California magazine, and San Francisco Classical Voice.

The Lily’s Revenge by Taylor Mac. The Chinese Lady by Lloyd Suh. Direction: Mina Morita; sets/props: Jacquelyn Scott; costumes: Abra Berman; lighting: Wen-Ling Liao; sound: Sara Huddleston. Oedipus El Rey by Luis Alfaro. Direction: Loretta Greco; sets/projections: Hana Kim; costumes: Ulises Alcala; lighting: Wen-Ling Liao; sound: Jake Rodriguez; dramaturgy: Sonia Fernandez; props: Libby Martinez; tattoo design: Jacquelyn Scott.