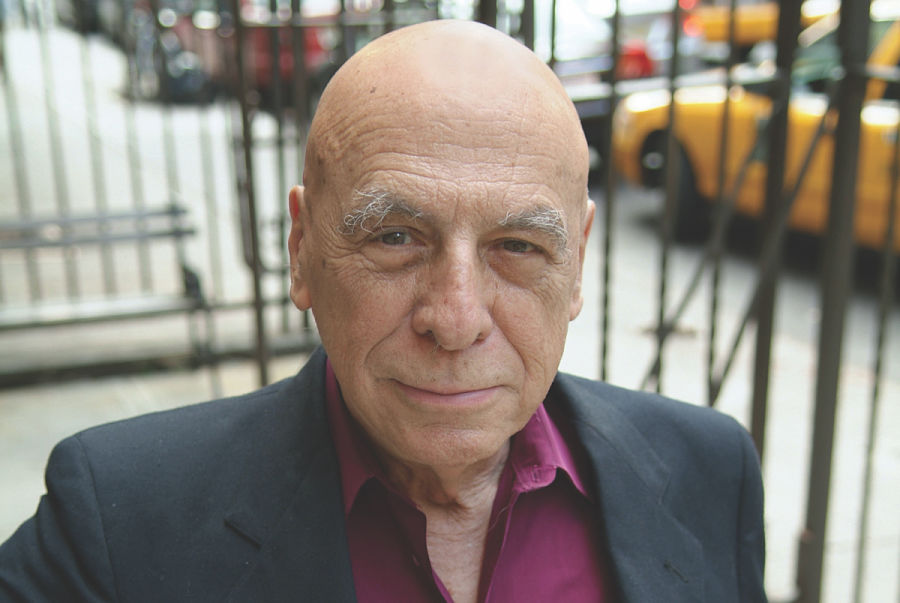

René Buch, co-founder of New York City's Repertorio Español, died on April 20. He was 94.

Amid the greying skies overwhelming New York City, as its citizens and economy suffer in the confusion and panic that has come to characterize life under the coronavirus pandemic, a message dropped into my inbox from director José Zayas: “Sad day. René has passed away.”

For a moment, the scant view of the grey skies outside my apartment window felt greyer still. Mischievous, brilliant, and exacting, René Buch had left this world at the grand age of 94.

It may be that some folks reading this may not know who René Buch was. But listen: There’s time to learn. If there’s one thing we know in this field, it is that memories can be short, but history is long.

Buch emigrated from his native Cuba, where he had been the founder and director of Pro Arte de Oriente’s Theatre Department and Havana’s Acción Teatral de Autores while also earning a law degree from the University of Havana, to the United States in 1949 to study at the Yale School of Drama. After obtaining his MFA there, Buch served as editor of the cultural section at El Diario La Prensa, and later as editor of the Spanish edition of the Journal of the United Nations.

In 1968 he returned to the theatre as a practitioner, serving as director of a production of Calderón de la Barca’s La dama duende at the newly formed Greenwich Mews Spanish Theatre, and in short succession, he co-founded Repertorio Español, the now-venerable Spanish-language theatre company situated at what is now the Gramercy Park Theatre that has been producing classics, modern, and contemporary plays for the last 52 years.

Buch was a pioneer in our field. At a time when New York City had not a single major theatre company dedicated to classical work in the Spanish language, Buch, the late Gilberto Zaldívar, and Robert Federico created a space for audiences to experience the beauty, range, and breadth of, initially, drama from the Spanish Golden Age through to the works of Federico García Lorca (about whom Buch was an expert), and later, incorporating into the repertoire newer works from the Caribbean, Central, and South America. Fighting a theatrical status quo that surely formidable at the time, Buch and Zaldívar and Federico made a vibrant space for Hispanic and Latinx audiences against all odds through a combination of sheer tenacity, will, talent, pluck, and luck.

Slowly, audiences did come. Most of them had been, shall we say, “forgotten” by the larger apparatus of New York City theatre. Along with Puerto Rican Traveling Theatre and INTAR (also initially created to be a Spanish-language theatre company), Repertorio Español tapped into a majority audience comprised of Spanish-speaking immigrants, first-generation children of Spanish-speaking immigrants, and transplants from other cities—audiences who wanted to hear not only the sound of their respective “homes” onstage but also to experience the glorious writing from Spain and the Spanish-language-speaking Americas that is still rarely presented on U.S. stages.

Repertorio’s initial mission to focus on the classics afforded them a unique position on the New York City theatre map. But what shouldn’t be lost along the way in thinking about Buch and Zaldívar’s legacy is that Repertorio also became home to a rotating company of actors, many of them immigrants as well. Founded on the repertory model, at Repertorio the same actors can perform in as many three different shows in one day while rehearsing two others. Preserving the nearly lost art of the rep system, with its unique demands on performers, was one of Buch’s tenets as an artistic director.

An exacting practitioner in the rehearsal hall, Buch was famous in the field for not suffering fools. He knew the classical Iberian texts, in particular, backward and forward, and he challenged actors and audiences to appreciate, celebrate, and be troubled by difficult works from the ‘other’ canon. Who else would have dared stage Lorca’s El Publico (The Public), for example? One of Lorca’s “impossible” plays, El Publico is a densely allusive, politically ferocious, defiantly queer and symbolic text. Yet Buch directed it at Repertorio in a production that on May 21, 1998 was lauded by D.J.R. Bruckner in The New York Times as one that would have little equal for “sustained emotional and intellectual excitement.”

Cutting his teeth in Spanish-language classical and contemporary work in Cuba and in New York, Buch also directed in the English language at Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Classic Stage Company, Milwaukee Rep, and the Old Globe Theatre in San Diego, among others. He received numerous awards throughout his long career, including a Drama Desk Award for Artistic Achievement (1996) and a Theatre Communications Group’s Theatre Practitioner Award (2008). He was awarded a Lifetime Achievement OBIE in 2011, and in 2012 was bestowed with the Order of Isabella the Catholic by King Juan Carlos I of Spain for his contributions to Spain-U.S. cultural relations.

His artistic legacy lives on in the folds of the emotional fabric of the company he co-founded, and in the lives of the many practitioners, administrators, funders, patrons, and audiences he impacted along the way. Below are testimonials from a select few who knew him well and whose lives he touched in significant ways.

Said Robert Federico, who as Repertorio’s executive producer worked closely with Buch at the administrative helm but was also as his frequent collaborator as scenic and lighting designer, “René taught me so many things: the glorious Siglo de Oro tradition and its integral sense of honor and religion; the lyricism and the bawdiness of zarzuelas; the symbolism of every single word in Lorca’s texts; the majesty of rotating repertory for an actor and a designer; the style of ‘less is more’; and the beauty of a working relationship that lasted almost 50 years. He was a master, and Repertorio Español will fight to continue his legacy.”

Playwright Carmen Rivera, whose play La Gringa Buch directed in 1996, and which is still in the company’s repertoire as the longest-running Off-Broadway Spanish-language play, said, “When I heard the news about René’s passing, I was heartbroken. When I first met him, I was so intimidated—he was the artistic director of Repertorio Español and he was going to direct my play. He had an imposing presence, with the deep voice to match. But I had nothing to worry about. René was a wonderful director to work with. He was welcoming and eager to collaborate. He was known for being demanding—and yes, he was quite demanding. But it was all to serve the art. His artistry was all about exploration and discovery—it was about the possibilities.

“I was so blessed beyond blessings that he directed La Gringa. I am 100 percent certain that his direction contributed to the success of the play. He explored time/space/light/sound—he wanted the play to exist beyond the words. We actually discussed this. It was a wonderful collaboration—it is how playwrights and directors should work.

“René Buch will be missed. He was a rare and special spirit! He taught me to look toward the beyond…I will treasure that for the rest of this life.”

Said playwright Eduardo Machado, “René Buch directed three of my plays: two Spanish productions at Repertorio Español, and one in English at the American Place Theater. I was in my late 20s when I met him, and still trying to find my way in the theatre. I was always impressed by how deeply he understood my plays. I remember him saying to the actors one day at Repertorio when he was directing, Revoltillo, ‘Why are you all thinking before you speak? Cubans don’t think; they just talk.’ Suddenly the scene started to work. He once told me that I described my sets in too much detail: ‘In Blood Wedding all Lorca tells us is that the set is blue; that’s it.’ His thoughts and directing talent liberated me from naturalism. It made me see that all you need is a stage and actors to create theatre.

“René was tough, direct, and blunt in his opinions. But when he loved you, he really loved you. I was lucky to receive René’s love and acceptance, and it made me believe in myself and gave me the courage to continue writing plays. I am forever grateful to him.”

Said playwright Nilo Cruz, “Besides being a fearless director at Repertorio Español, René was a visionary and a very wise and knowledgeable artist of the theatre. I remember meeting him when I was a student in college, he came to Miami to do a lecture for the Hispanic Theatre Festival, and I was riveted by his words and his sensitivity about theatre. Little did I know that he would later direct my plays in New York. I had the great fortune of working with Rene on Lorca in a Green Dress, and it was a feast to explore the text with him and find the meaning and subtext behind every phrase and word. He was a passionate man, with an excellent taste, who was very well acquainted with the texts of the great masters. He was loving and understanding, but also quite demanding. He was also very opinionated, in the way that most Cubans of Catalan descent have very strong opinions, but his take on life always had an insightful foundation. He shall be missed. We are extremely grateful for his groundbreaking work and the legacy he left behind.”

José Zayas, who was resident director at Repertorio from 2009 to 2015, “René carved a path where there was none. He inspired generations of Latinx artists to learn from their heritage while finding a path forward. I will always admire his dedication to spareness, his scholarship, his puckishness, his trust in the audience’s imagination, and his belief that theatre is a space for introspection and adventure. Repertorio Español provided a home for me as an up-and-coming director (I had the privilege of directing 17 plays for the company). I never thought I would get the opportunity to work in Spanish in the United States. His theatre opened these doors wide and showed me that there was a community hungry to connect with each other and with stories that spoke in a language many were taught to forget.”

Rosalba Rolón, artistic director of Pregones/Puerto Rican Traveling Theater, recalled, “It was my lucky day in 1978. I was an emerging actress in New York City and was participating in a theatre workshop. On that lucky day, the director told us she had a special guest. His name was René Buch and he was the artistic director of Repertorio Español. I held my breath. I had heard of him and of the company. This was big! In walked René, smiling eyes, hands in pockets. We all paused. ‘Don’t stop. Keep going,’ he said, still smiling, but make no mistake—he meant it. “Keep going.” And with that, I met one of the most influential directors in NYC’s Spanish-speaking theatre arena. He trained, mentored, and inspired hundreds of actors and directors over the course of his 50-plus-year career. He was a skills builder, an actors’ director. As my career as an actress and director developed, I co-founded Pregones Theater. I always knew René was just a phone call away. We have lost one of the great artists of his generation. His words still ring: ‘Don’t stop. Keep going.’”

Actor Luis Carlos de La Lombana, who was directed by Buch several times, chief among them, including in the role of Segismundo in Calderón de La Barca’s Life Is a Dream, said, “René had such a rich personality and that much to offer that I will talk just about him as a person which is what ultimately means more in any human being (no matter how interesting, wise, well prepared, and cultured an artist he was).

“From his legacy as an artist I will only mention something I will never forget that he said in a Q&A at Repertorio Español after one of our performances of Life Is a Dream. An audience member asked him, ‘Mr. Buch, what difference do you find between Segismundo, the lead character in Life Is a Dream, and Hamlet?” René replied, “Well, first of all, Hamlet has better marketing…And then I would say, Hamlet is more complex psychologically and Segismundo is more complex philosophically.

“He was able to say something profound with a minimum of words. This was a measure of his wisdom.”

As for René the PERSON—and I say it with capital letters—he was someone that had strong values and he was a true gentleman. He was loyal, brave, respectful, in its more qualified sense, generous, compassionate, discreet, noble, and forgiving; he chose to see the best in people rather than be resentful or punishing toward them. As someone that became a close friend to him, especially in his later years, he was a prince among men, the kind that sometimes, if you are lucky, you get to meet in your path through life.”

Director Estefanía Fadul said, “When I was a directing fellow at Repertorio in 2014, René was already long retired from the company and in declining health. I would hear about him often from longtime company members, many of whom would speak excitedly about going to visit him, and always refer to him with the greatest love and respect. To me he was something of a legend, and I couldn’t believe it when I was told one night that he was in the audience at one of my shows there. His making the effort to come out and to support the work of a young director he didn’t know felt like an incredible gesture of generosity and investment not just in the company he had created, but in the continuing development of Latinx artists. Meeting him after the show, and experiencing his warmth and kindness in person, is a moment I’ll never forget. I’ll be forever grateful for his vision of creating community around Spanish-language theatre in NYC, and a home for Latinx and Hispanic artists of all generations.”

And Emilya Cachapero, director of artistic and international programs at TCG, said, “René was and continues to be one of my personal heroes. I remember meeting him and seeing his moving work at Repertorio Español when I moved to NY in the late 1980s. We bonded over the similarities in Cuban and Pilipino language, food, and culture. He was uncompromising in championing classic plays, and in his gentle way pushed me to consider Calderón de la Barca and Lope de Vega in a more thorough way. I clearly remember visiting OSF and watching a run-through of his Romeo and Juliet, and how he created a room filled with warmth and generosity. May René’s legacy live on!”

Since 2009, Caridad Svich had four shows commissioned by and produced at Repertorio Español, among them The House of the Spirits, based on Isabel Allende’s novel.