“The weight of this sad time we must obey.”

—final speech of King Lear

If a dramatic scenario in real life is epic enough, people might call it biblical. But if it is also knotty and complex, they’re likely choose the quintessential theatrical reference, says actor and drama professor Gary Sloan. “This thing we are living through now is Shakespearean, so we want to engage it in Shakespearean terms,” says Sloan.

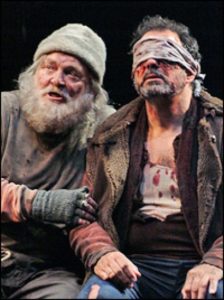

That’s the thinking behind the Zoom King Lear reading Sloan is staging on April 23, Shakespeare’s 456th birthday. It stars Stacy Keach (from California) as Lear and Edward Gero (from Washington, D.C.) as Gloucester, reprising roles from the production directed by Robert Falls in Chicago in 2006 and D.C. in 2009. The reading hopes to raise money for food pantries, both near Yardley, Pa., where Sloan lives, and nationwide.

“Zoom theatre is creating a whole new world,” says Keach, whose daughter, Karolina, will play Regan.

“We’re like monks in Middle Ages preserving the most important books,” Gero adds. “We have to carry the culture forward. Shakespeare especially resonates now as people feel an existential threat. It’s our way to hold on to what we value most.”

Sloan, who is retiring from his post in the theatre department at D.C.’s Catholic University, recently began introducing theatre productions, including A Christmas Carol, at his local church, St. Andrews Episcopal. He was in the midst of planning a possible summer Shakespeare production when the coronavirus pandemic struck. To provide a sense of community for parishoners, he suggested a Zoom Shakespeare course.

“Then my brother sent me an article about Shakespeare writing King Lear in 1606 during the plague, so I decided to do this reading instead,” he says.

The popular notion that Lear was written while its author was in quarantine in 1606 has shot around the internet since the pandemic shutdown (and as a trope it has been, if not quite debunked, then questioned). Of course, pandemics were fairly common then: Shakespeare was born during one, and London playhouses were reportedly shut down for perhaps 60 percent of the time between 1603 and 1613. He probably wrote Romeo and Juliet shortly after the time of a 1592-93 lockdown; Friar John’s quarantine leads to the play’s tragic ending, and “plagues” are referenced in that play, as they are in King Lear (the monarch’s curses include “Vengeance, plague, death, confusion,” and “a plague-sore or embossed carbuncle / In my corrupted blood”). In 1603-4, when roughly 20 percent of London residents died, Shakespeare, locked away, wrote Measure for Measure. In 1606, in addition to Lear, he may have also worked on Macbeth and Antony and Cleopatra.

Station Eleven, Emily St. John Mandel’s bestselling dystopian novel from 2014 about a flu that nearly wipes out all of humanity, opens with a performance of King Lear. Mandel wrote that scene for Arthur, the show’s star, who dies of a heart attack onstage, even before devising her “Georgia flu” plot, but then saw it perfectly set the story’s tone. “It’s very much a play about losing absolutely everything in your life,” says Mandel.

With permission from Actors’ Equity Association, Sloan was able to scale up his modest church reading up to one that mixes local non-professional actors with Gero and Keach, two powerhouse actors with long pedigrees in Shakespeare, among many other works. In fact the new reading braids together more than one previous professional cast: Exactly 30 years ago, on April 23, 1990, King Lear opened the Shakespeare Theatre at the Folger in Washington D.C. , with Sloan as Edgar and Gero as Cornwall. That show’s Edmund, Daniel Southern (now a doctor in Connecticut), will, like Sloan, reprise his role, though Gero will play Gloucester.

The Keach connection also goes back some way, though not to the same production of Lear. In 1995, Sloan was part of an effort to help preserve Tudor Hall, home of the Booth family—notorious for John Wilkes but beloved by Shakespearean actors for Edwin and Junius—so Gero introduced him to Keach, a fellow Booth-phile, who then agreed to play Macbeth in a benefit for the cause.

Though it’s a reading, the cast has been rehearsing, which has been a learning experience for all.

“Zoom theatre is a new language, a whole new way of expressing yourself as an actor,” says Keach, who notes that he recently saw a good Hamlet online from England and has been impressed by the Show Must Go Online, which is performing all of Shakespeare’s plays in this new format. “Our show is an experiment. As time goes, we will all become more conversant and creative with, and less intimidated by, the technology.”

Technical issues are varied. Gero mentions the slight delays in Zoom transmissions, and Keach notes that when an actor is “offstage,” they are supposed to mute their computer, but “invariably people forget to take the mute button off the next time they speak.”

Keach says actors must adjust how far they want their face from the screen and how to best light themselves—he says he’s been impressed by, and a tinge jealous of, Gero’s self-lighting work. Gero, who has been teaching drama at George Mason University for weeks via Zoom, says it’s all done with a desk lamp near his face.

Sloan notes that a narrator will read stage directions, and as a director he has been advising the performers on camera distance and backgrounds. But with such a far-flung cast, in a new medium, he says, the approach is “all hands on deck.”

Then there are the matters of mood and chemistry. While Zoom offers both less scope and more intimacy than theatre, Gero says, comparisons to film or television aren’t quite apt. “In film you’re not looking straight into the camera,” he says. “It’s more about vocal technique, like radio.”

Looking at the camera atop your computer is problematic, Keach adds, since you can’t see your scene partner to play off their reactions without glancing below to find their square. “It’s hard to fly right now, but we are learning every day.”

The reading won’t use props and will have a simple black background. But Keach and Gero expect work in this format to grow more sophisticated, with Gero suggesting the eventual possibility of actual scenic backgrounds. He could also imagine a two-hander in which actors sit in profile so it appears they are talking to each other.

Given how long actual theatres may be missing from our world, the actors expect to see a broadening palette, including perhaps new works about the virus. In Station Eleven, a traveling theatre troupe finds that in a post-pandemic world audiences prefer Shakespeare to new material, though Mandel says she’s not sure how she feels in real life. “It’s one thing to say that in a fictional pandemic scenario, but it’s another to live it.”

For now, Sloan says, King Lear, despite its dire, haunting look at humanity, can help us cope. “It is inspiring us as actors to better ourselves, to dig deeper and to find something new,” he says, before quoting Edgar, on the run in the wild weather, and facing an uncertain future.

To be worst,

The lowest and most dejected thing of fortune,

Stands still in esperance, lives not in fear:

The lamentable change is from the best;

The worst returns to laughter. Welcome, then,

Thou unsubstantial air that I embrace!

The wretch that thou hast blown unto the worst

Owes nothing to thy blasts.

King Lear will stream live, and for free, at 7:30 on April 23 on the following sites. It will also be available for streaming for four days afterward.

St. Andrews’s Facebook page

St. Andrews’s YouTube page

St. Andrews’s website

The production is raising money for the Penndel Food Pantry in Bucks County, and/or you can donate to one in your area through https://www.feedingamerica.org/find-your-local-foodbank.