The following is an excerpt from the new book Stages: A Theater Memoir, which recounts Albert Poland’s career as a New York theatre producer.

In 1976, Howard Ashman asked his friend Kyle Renick if he wanted to start a nonprofit theatre company. Kyle was the business manager of the American Place Theatre and Howard was an editor at Grosset and Dunlap. Soon after they took over the floundering WPA Theatre and immediately put it on the map. The opening productions were an Albee adaptation of Ballad of the Sad Café and Gorey Stories, a revue mentored by Ashman that moved to Broadway.

Howard spent the next six years honing his craft as a writer and director, and he began a collaboration with Alan Menken, who he met in Lehman Engel’s BMI Musical Theatre Workshop, as his composer. In 1982, with Howard as author, lyricist, and director, Ashman and Menken created a show that had 25 commercial producers in hot pursuit. It was called Little Shop of Horrors, and I’ll never forget Kyle’s breathless phone call telling me he was considering me as a possible general manager. I rushed to see it that night.

What I saw was a certified hit. Hits have a swagger that nothing else has, and it was right there from the very first note of music to the finale. I ran home to call Cameron Mackintosh in London. He was, of course, asleep. I told him I had found a huge hit. “You have to do it. Everyone in town is after it. I’ll get you a tape.”

“Call Bernie,” he urged.

Bernie was, of course, Bernard Jacobs, of the Shubert Organization. I called him that morning to tell him Cameron and I wanted him to see the show. Could he go tonight? He could, and he promised to call on Saturday morning with his report. Excited, I told Kyle I had spoken to Cameron, and that I needed four tickets for Bernie.

He told me that Esther Sherman, Howard Ashman’s agent, had arranged tickets for David Geffen the following night. Esther and I were very close, and she was thrilled when I told her about Cameron and about Bernie seeing the show.

Bernie called me early Saturday as promised. “It wasn’t my cup of tea,” he said, as I sank. “Betty didn’t much care for it. The young couple we were with enjoyed it. It has a lot of whimsy. The British like that kind of thing.” He added, “But if you want us to come along, we might consider it.”

On Saturday night, David Geffen was a no-show. On Monday, just to be professional, I put in a follow-up phone call to Bernie. I’ll never forget his return call. “Albert, I have David Geffen on the line. We will take the show. How much will it cost?” Not having even thought about a budget, I blurted out the first figure that came to my mind. “Three hundred fifty thousand.”

“Do you want to come along, David?” Bernie asked.

“Whatever you say, Bernie.”

“You’ve got to leave room for Cameron,” I said. “He is the one who suggested I call you.”

“Very well. Come to my office on Wednesday,” Bernie commanded, “and bring the budgets.”

In true Bernie style, he spent the next two days telling the industry he was doing Little Shop of Horrors. He would later claim that he decided to do the show when Alexander Cohen, a rival producer who attended the same performance, told him it would never work. “If Alex didn’t like it,” he said, “I knew it would be a hit.”

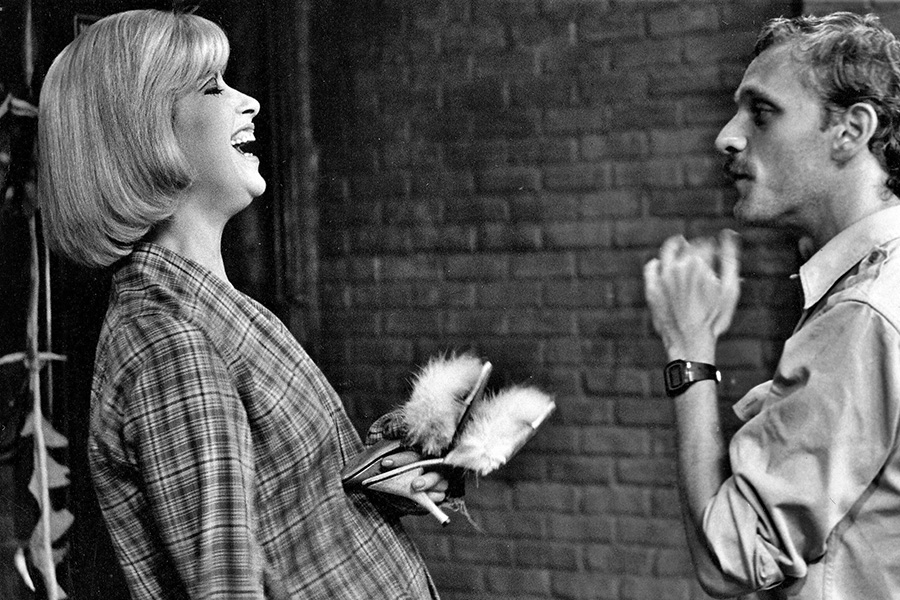

I started work on the budgets, and Kyle, Howard Ashman, and I began checking out theatres. It was my first time meeting Howard, and I found him to be rakishly handsome, to the point, and brilliant. He was exhausted from directing the show but focused and intense. We were going into summer, and the only venue available was the Orpheum on Second Avenue and St. Mark’s Place. The Orpheum had a long track record of hits and was fine, except that its 299-seat capacity fell short of the economic requirements of the show. Fortunately, the resident WPA set designer, Edward Gianfrancesco, was also an architect and contractor. He told us that the Orpheum could accommodate the addition of a balcony, giving us the capacity we needed.

On Wednesday, I went in for my meeting with Bernie Jacobs. I arrived at his office, which was something out of MGM, to see him sitting at his desk with toilet paper stuck to his cheek. In the middle of it was a small red stain. He was yelling into the phone.

“Mr. de Rothschild, I can’t hear you! Mr. de Rothschild, I am in the business of selling tickets. No, I cannot give you free tickets. Mr. de Rothschild, I can’t hear you.” And he hung up.

“Did he want a pair of comps to Cats?” I queried.

“A pair? He wants an entire house. He’s doing a fundraiser, and he thinks I should contribute the tickets. What is he, anyway? Just a Jew with a ‘de’ in front of his name.”

“By the way,” he said, looking at my flat top, “how do you get your hair to stand up like that?”

“Actually,” I said, “when I get on the elevator to come and see you, it’s lying down.”

Watching this unabashed man with toilet paper stuck to his face, I had my first realization that Bernard B. Jacobs was a man who was himself at all times.

“Do you have the budgets?”

“Yes, but Bernie, I have to tell you something. You don’t have the rights.”

“Well, what does he want?” Bernie barked.

“What are you willing to offer? There are 25 people chasing after it, but you are you.”

Within seconds, Bernie structured an offer. It acknowledged who everyone was, the value of what they brought to the table, the value of the property, and the need to be competitive with the other bidders. “The offer is brilliant,” I told him. “If I can’t deliver it, I won’t be on the show.”

He looked at the budgets and said he didn’t know anything about Off-Broadway, so he would have to trust that I knew what I was doing. “By the way,” he said, looking at my flat top, “how do you get your hair to stand up like that?”

“Actually,” I said, “when I get on the elevator to come and see you, it’s lying down.”

David Geffen and I met for the first time on opening night in front of the Orpheum. He was understandably nervous. He was the producer of a show he had never seen. I assured him he would be very happy. The opening “Skid Row” number was greeted with rousing applause, and we were off and running.

At intermission Geffen made a beeline for me, gave me a big hug, and said, “Albert, it’s a great big smash.” After the performance, we had our opening night party—wine and cheese in the lobby of the Orpheum. The reviews were spectacular. Not just raves, spectacular. Business was solid, but I told the producers we would not have a sellout week until October. We were in the middle of July, and I had enough Off-Broadway experience under my belt to talk about buying patterns with certainty.

Tommy Schlamme outdid himself on our TV commercials, and they became famous in their own right. Little Shop was sold primarily on television.

The stars came in droves, and I gave the house manager a Brownie Hawkeye camera. He was to take photos and get the film to our press agent, Milly Schoenbaum, who would have them rush-developed and get them to the press. For each photo he took, I gave him $25. If it ran in the paper, an additional $25. The following months and years brought Steve Martin, Eddie Murphy, Mary Tyler Moore, Harry Belafonte, Steven Spielberg, Robert Redford, Barbra Streisand, Sidney Poitier, Lucille Ball, Dustin Hoffman, Bette Midler, and many others.

Almost as if by magic, October brought us our first sellout week. And we stayed in that position for years. The show would now make a profit of $6-8,000 a week. I was happy. I had always considered $3-5,000 to be a good weekly profit for Off-Broadway.

As we enjoyed our first sellout week, Cats opened on Broadway. I had flown my mother and father in from Michigan, and we attended opening night with Art D’Lugoff and his wife, Avital. Twenty minutes into the performance, my mother leaned in to me and said, “Isn’t this monotonous?” Otherwise, it was an evening of high glamor.

The following day, Bernie showed me the accountant’s statement for the first week of Cats. In one week it had made an operating profit of $186,000. I was stunned. The critics’ reviews were mixed-to-negative.

The next day Bernie had a tag line placed under the title in all the Cats advertising: “Now and Forever.” Howard Ashman said there was only one man who would put that in an ad after those reviews.

After the great success of Cats, the phone call from Phil Smith, the Shubert Organization’s executive vice president, was inevitable. “Bernie wants you to come over here to discuss the implementation of the new ticket prices.”

I urged Cameron to come with me. “We have to fight this,” I told him. Bernie had brought up increasing our ticket prices several times, but I had so far stemmed the tide.

Bernie started. “Phil keeps saying to me, ‘Why do you let Albert push you around?’”

“You will destroy my turf,” I said.

With Cameron sitting in total silence, I realized we were dealing with a fait accompli.

We raised the ticket prices. I bore enormous guilt. And I wasn’t the only one who felt Off-Broadway was being damaged. In the middle of dinner, my good and revered friend Dorothy Olim attacked me. Dorothy was the conscience of Off-Broadway. I went home and cried all night long.

In addition to the new ticket prices, Bernie wanted the royalty participants to defer 20 percent of their royalties to hasten recoupment of the production costs. I battled to no avail with Esther Sherman and Scott Shukat, who represented Alan Menken and the choreographer Edie Cowan. I called Bernie to tell him, and he got Esther on the line and read her the riot act. Before it was over, she had agreed.

He called me back. “You’ve got to be a killer, Albert. You’ve got to be a killer. You’re not tough enough, Albert. But I love you.” Vintage Bernie.

I grew to love him very much. He was a great motivator. I found myself lying awake at night thinking of things to do for the show that would please him. He constantly told me he loved me, and, equally important, I had his trust. He gave me free rein to run the show. As a matter of procedure, I called for his approval before I made any major decisions, especially financial ones. The usual answer was, “Whatever you say, Albert.”

At Christmas, Howard Ashman gave me a large handmade doll of Judy Garland as Dorothy. It meant a lot because we both loved her so. With it was a note: “Albert. Christmas is always a good excuse to get sentimental (for me, anyway). And this, of all Christmases, is a special one for me. You’ve done so much toward making that happen and I just hope you know that none of your care and work and time and smarts, none of the above, goes without notice, deep deep appreciation, and an inner smile from me. Thank you. May we be part of each other’s lives many Christmases more. May you have all the wonderful things you deserve. Love, Howard.”

By spring, it was time to consider the first Little Shop production outside of New York. Bernie and I thought it should be in an eastern city like Boston. David Geffen wanted it in Los Angeles, and he prevailed. We scouted for theatres, and I was heavily in favor of the Roxy, a Village Gate-like cabaret where Rocky Horror had run for years. Howard ruled it out immediately. “I don’t want glasses tinkling during my show,” he said.

Largely because of its proximity to UCLA, the producers chose the Westwood Playhouse. No location in Los Angeles was ideal because the town was completely spread out and was full of so-called “Equity Waiver” theatres that offered shows at $10 a pop within blocks of people’s homes.

Milly Schoenbaum, our superb press agent, was employed by a large public relations firm owned by Lee Solters and Sheldon Roskin. Solters was now based in Los Angeles and had heavyweight clients like Frank Sinatra, Barbra Streisand, and Michael Jackson. He personally wanted to handle Little Shop in L.A., but, for reasons he did not explain, Bernie wanted nothing to do with him. Solters applied substantial pressure to Milly to at least deliver a dinner with me, and I convinced Bernie that it was the politic thing to do.

At the dinner, Solters went out of his way to charm me and was brimming with ideas for selling the show in Los Angeles. I liked him and would have gone with him. But I reported back to Bernie, and he was still adamant. He favored Judi Davidson, who was indisputably the top theatre press agent on the West Coast.

I joined Howard in Los Angeles at the beginning of rehearsal. As the opening neared, the Shubert’s top brass—Jerry Schoenfeld, Bernie, and Phil Smith—arrived. They were relaxed and happy. Jerry, dressed casually in a cardigan sweater, took me for a long drive through Beverly Hills. “Behind those windows, Albert, are some of the wealthiest people in the country,” he said.

“And what are they doing behind those windows?” I asked.

“Clipping coupons.”

Little Shop opened in Los Angeles on April 28, 1983. Before the show, Jerry Schoenfeld spotted Dan Sullivan, the Los Angeles Times theatre critic, and called him over to introduce me. I winced as he said, “Dan, I want you to meet the king of Off-Broadway.”

“Well,” Sullivan exclaimed sarcastically, “I’m always happy to meet the king of anything.”

After the blowout performance, Howard asked all of us to come into the auditorium. He and Alan had a new song they wanted to do for us. It was called “Sheridan Square,” and we were hushed as they sang it so plaintively. It was about the blight of AIDS on what had been for decades one of the happiest gay areas in Greenwich Village. The epidemic was now claiming its first victims. Even with available medication, it was a matter of time. Having it was a death sentence. Stuart White, an early companion of Howard and a founder of the WPA, was to die in July after a long illness. The theatre community was devastated by the epidemic. The gay community was devastated and terrified.

The next day Dan Sullivan savaged us in the LA Times. He said, among other things, “This show thinks it’s so funny, it doesn’t need an audience.” The other reviews were all superlatives, but Sullivan’s review hurt us, and Little Shop did not perform to our expectation. I continued to wonder who or what caused Dan Sullivan to write that damaging review. Did Lee Solters have a word with him?

Howard asked all of us to come into the auditorium. He and Alan had a new song they wanted to do for us. It was called “Sheridan Square.” It was about the blight of AIDS. The epidemic was now claiming its first victims. Even with available medication, it was a matter of time. Having it was a death sentence.

We returned to New York just in time for awards season, and we won everything—the Drama Critics Circle, Drama Desk, and Outer Critics Circle Awards for Best Musical of the Season. My old friend Michael Feingold, drama critic of The Village Voice and head of its Obie Awards committee, was at the Drama Critics Circle Awards. I went over to him with my third martini in hand and opened with, “This will never win an Obie because it’s not in a basement, more than three people have seen it, and no one from the Voice has ever slept with any of us.”

“Oh, sour grapes,” Michael responded.

“Albert’s right,” Esther Sherman chimed in. “The only award you’ve given to a commercial show in the last 10 years was Bloolips for Best Costumes.” Glancing over at Lucille Lortel, who was standing nearby, I added, “We’ll get our own awards for commercial Off-Broadway.”

I brought it up the next morning at a meeting of the League of Off-Broadway Theatres and Producers: the Lucille Lortel Awards. Everyone liked the idea. George Elmer asked, “Do you think Lucille will go for it?”

“Go for it?” Paul Libin replied. “She’ll pay for it.”

As it happened, that night was the opening of a double bill of Beckett one acts at the Clurman, co-produced by Lucille and Jack Garfein. At intermission, I approached Lucille on the sidewalk and told her of my idea.

“How much will it cost, dear?”

At the same moment, Ben Sprecher opened the newly refurbished Promenade Theatre, from which I had rescued Liza Minnelli five years earlier. He brought his brand of professionalism to it and made it the most sought-after and most expensive theatre Off-Broadway. But this time, he was working for himself as co-owner. Producers, without exception, wanted to put their shows there.

The synchronicity of Ben Sprecher’s approach to theatre operation and the lucrative Little Shop profits were driving Off-Broadway from scotch tape and paper clips toward the realm of big business. Bernie was ready for yet another increase in ticket prices.

“It’s the Jacobian Theory,” I said, resigned.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“What goes up must go up.”

The David Geffen-produced film of Little Shop premiered in New York at the end of December. Howard wasn’t that happy with it, but it should be said that Howard’s happiness was never a slam dunk. The movie did well at the box office and drove our business way up for several months.

In the fall of ’87, business dropped sharply. After a month of operating losses, I called Bernie and told him I didn’t see it coming back. It was as if the public had suddenly had enough of us and moved on.

No playwright has ever agreed with the decision to close a show, this one included. “You’re closing it too soon,” Howard protested. “Howard, we have run five and a half years!”

“I’m telling you . . .”

When Little Shop of Horrors closed on Nov. 1, it had run 2,209 performances and was the highest-grossing show in Off-Broadway history.

In the summer of 1983, our company manager Nancy Nagel Gibbs had taken the first of two maternity leaves and was replaced for three months by Peter Schneider. During that time, Peter struck up a friendship with Howard Ashman and Alan Menken that was to have an impact on the entertainment industry none of us could have possibly imagined. After Peter left us, he moved to Los Angeles where, in 1985, he became the first president of Disney Animation. He brought Howard Ashman and Alan Menken along with him, beginning a 10-year renaissance at Disney that changed animation forever. The films they made together—The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and Aladdin—set world box-office records and won multiple Academy, Golden Globe, and Grammy Awards. Beauty and the Beast was the first animated featured to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture.

After the 1990 Academy Awards, where they collected two Oscars for The Little Mermaid, Howard told Alan that he was HIV positive. Peter instructed the animators on Beauty and the Beast that they were now to work with Howard in New York. With time, the reason became apparent. His health was deteriorating rapidly.

Near the end, I spent an hour alone with Howard at St. Vincent’s Hospital. His sight was going, and he said everything was as if by candlelight. We spoke fondly of our time together and agreed that, with Little Shop, we both became what we had been becoming. It was our goodbye.

Howard died on March 14, 1991. He was 40 years old.