I think of George Devine often.

I think of George Devine often.

In 1956 he founded the English Stage Company at the Royal Court Theatre. To hell with bourgeois misery, he said; he demanded “uncompromising, hard-hitting” plays about “the problems and possibilities of our time.”

Maybe it’s holy writ now, but with Grab Me a Gondola in the West End, Devine was punk rock. Ten years of war with patrons, censors, and philistines of all sorts bought him several nervous breakdowns, heart attacks, and the stroke that killed him at 56.

Devine’s legacy is in every new-writing theatre. But he thought himself a failure. “I wanted to change the attitude of the public towards the theatre,” he said. “All I did was change the attitude of the theatre towards the public.”

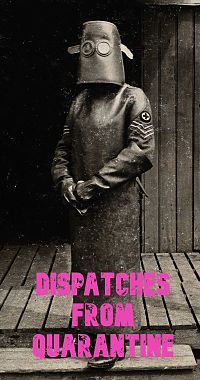

So don’t stick Devine’s picture on the wall and salute. He’d smack you. Instead, look over your shoulder. There he is. Mug of tea, corduroy coat pulled against the cold:

“You should choose your theatre like you choose a religion,” he says. “Don’t end up in the wrong temple. You must decide what you feel the world is about, so that everything in the theatre you work in is saying the same thing.”

Now he puffs his pipe, stares over thick spectacles. His tone is that of a kindly priest who’s been to hell and back. He wants to save you the trip.

“A theatre must have a recognizable attitude. It will have one, whether you like it or not.”

I’m a mess.

A mild case of COVID-19 laid me low for three weeks. The fever is long gone, but it’s difficult to write this. I feel like I speak Ancient Greek.

I’ve lost gigs. I worry about my family, my neighbors, the general election, buying toilet paper. My neighborhood is quiet but for sirens. I’ve turned into Tony Soprano, shuffling outside in my bathrobe, looking for killers in the bushes.

Hell, I cut my own hair. But I’m alive, at least, and the plague didn’t manage to infect the room upstairs where the characters live. (No wonder they drink; it looks like a Super 8 Motel.)

I have to look after them. And keep Devine from haunting me. Like it or not, that means sorting out my attitude.

A hysterical and maudlin anonymous article claims our collective dissociation is proof that theatre has reached its limit. Don’t bother trying to meet the moment, it says. Stories are vulgar these days, and we can’t measure up anyway—especially not with technology. Best to bow our heads, grieve, and wait for …

What?

Our correspondent says “the virtual play readings, the 1-minute quarantine play scripts, the archival production footage” are no substitute for gathering together. How can they stand up to overflowing morgues?

He’s right. But is the moral thing to hunker down with Netflix and prepare to …

Welcome the inevitable Friends musical to Broadway?

I’m not arguing against escapism or for productivity. Whatever gets you through the night. But I do think most of us believe in art in a way “Nicholas Berger” doesn’t.

We don’t sell widgets. (That’s what pilot season is for.) Instead we practice a religion, a way of life built on the chance of connection in shared doubt.

We often miss the mark. But Harold Pinter describes the process like this:

[T]he image must be pursued with the greatest vigilance, calmly, and once found, must be sharpened, graded, accurately focused and maintained … the key word is economy, economy of movement and gesture, of emotion and its expression, both the internal and external in specific and exact relation to each other, so that there is no wastage and no mess.

These are the limits quarantine imposes on us.

We’re broke.

Many producers won’t return. Others will survive by radically changing how they operate.

We’ll gather again. But not in the same places, the same ways. So I can’t call experiments in digital theatre sanctimonious Band-Aids, as Berger does. I don’t even think they’re ways to mark time between bed, the couch, and Ozark.

They’re notes on strategy. Sketches for plans of attack.

We remind ourselves that words are still king. Magic is not the same as spectacle, and introspection must be balanced with a cold look outward.

We must accept that theatre isn’t always theatrical—at least not in the let’s-uproot-trees-and-climb-Everest sense. Krapp’s quiet sigh in a dark room is all we need; a desperate person sending energy through time and space. To us.

And we must reconsider our idea of what the audience wants, what sells. If a focus group likes I’m Not Rappaport for next season—well, maybe. But peer-reviewed studies going back 2000 years say that when things go to hell, people crave stories of all kinds, and find solace or provocation in odd places.

Don’t end up in the wrong temple.

Our work starts with listening and reflection. We have plenty of time now. But if you have the itch to respond, scratch it.

Not every bake-off microplay is a step forward. I pass on many through my awful attention span. And let’s face it, what are they but reminders of this mess?

But listen: There’s the hiss of distillation. The scrape of knives sharpening. A stumble towards images, perhaps even the renewal of faith.

Who has power? What does it mean? Where does it come from? What threatens them?

Devine paid a heavy price for letting these questions rule his work. Now history grinds our noses in them again.

We can sit tight, mourn the dead, feel sorry for ourselves, hope for the best. Or, in the face of catastrophic failures of political power, we can get leaner, meaner, more skeptical and immediate, willing to let our work live in the same moral gray areas we do.

They can’t kill us all. We can only hope to pull the theatre further from the middle-class fancies that plagued Devine, back toward the crowded center—where everything is wrong and all is possible.

Justin Sherin’s plays have been developed or produced at the Royal Court Theatre, the Old Vic, the Royal Shakespeare Company, 59 E59, Yale Cabaret, and elsewhere. Follow him on Twitter at @wychstreet or @dick_nixon.