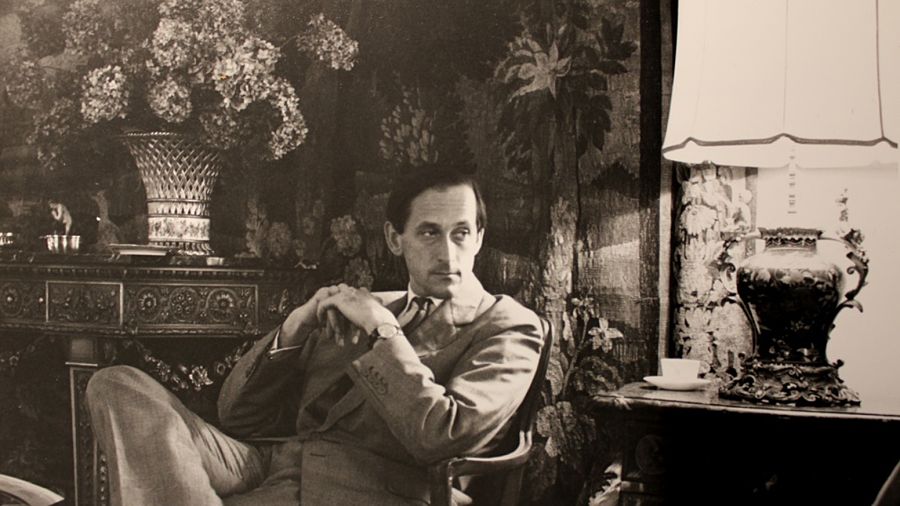

My impressions of André Gregory—as the sage raconteur with the lupine gleam in his eye from My Dinner With André, or the the guru-like director of nearly private yet hugely prestigious theatre productions (The Designated Mourner, Uncle Vanya), or even the wild-eyed John the Baptist from Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ—did not prepare me for the lively, congenial phone chat I had with him a few weeks ago. The occasion was the imminent publication of his new book with Todd London, This Is Not My Memoir (now pushed to a November release date), which recounts a veritable whirlwind of a life onstage and off. Born in Paris in 1934 to secular Jews from Russia, Gregory grew up in Los Angeles but never took to its native medium, film. Instead, educated at Harvard and Lee Strasberg’s Actors Studio, he set out for a career as a stage director at Philadelphia’s Phoenix Theatre, San Francisco’s Actors Workshop, and Los Angeles’s Inner City Cultural Center. After making a name for himself with a troupe called the Manhattan Project, whose signature success was 1970’s wild and woolly Alice in Wonderland, he burned out and flailed for years until reemerging as Wallace Shawn’s partner in the famous 1981 film bearing his name. He has seldom been away from the theatre, or acting roles, since.

Our conversation ranged widely, from the lessons of his peripatetic life to our current moment of global crisis. It is a mark of his thoroughly disarming graciousness that he made me feel that, had we the time, we could have talked all day—even into dinner.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: I devoured your book, and I just need to say a real quick fan thing: It was your production of Uncle Vanya that made it my favorite play.

ANDRÉ GREGORY: Oh, thank you. Did you actually see the play or are you talking about the movie?

The movie’s about as close to the play as you could possibly be.

Yes. I was later in a production, as a servant playing the guitar. So I’ve probably seen that play more than any other, but yours is still my favorite version of it.

What an amazing play. I would watch it every night. I probably saw the production about 200 times. And in spite of that, I could not figure out the structure of the play. It remained a mystery. You probably felt that watching it.

Yeah, it’s a bit like a song where I know how the words go once people start singing it, but I couldn’t tell you how it goes once the song stops, you know?

Yeah. But Louis Malle certainly did a gorgeous job of capturing what we did.

Can you tell me a little bit about the title, This Is Not My Memoir? Are you deflecting, or just being impish?

Well, it’s certainly partly impish. It’s also partly that there were two things I knew I would never do: Climb Everest and write a memoir. When FSG approached me, which was sort of an offer, I couldn’t turn down. I got trapped. But normally I would have never written a memoir. And of course, as you could see from the structure of the book it’s not quite a memoir. Also, I suppose because I’ve been in the theatre so long, there’s a character who changes in the process.

I was very driven when I was younger. I wanted to be Stanislavsky. I was filled with absurd goals like that.

That’s true. Do you feel you have not had a stable, fixed personality through your life, or that when you look back on it, it just naturally forms into chapters?

Well, I would say many of us change over a lifetime, and mine has been such an extraordinary life that I’ve simply not stayed the same person. I think I’m a radically different person now. The character in the book begins as an angry, somewhat bitter, frightened, uncertain loose cannon, and over time—at least, this is what I was trying to do over time—he becomes a gentler, kinder, and less driven person. I was very driven when I was younger. I wanted to be Stanislavsky. I was filled with absurd goals like that.

Were you always able to stand outside yourself in this way—to talk about yourself as if you’re a character?

Well, I wasn’t able to do that when I was younger. But I think as I got older… You know, when you’re directing, you’re feeling—at least I do—a lot of the emotions of what the actors are going through, and at the same time there’s this objective eye that is watching and thinking. So you’re not thinking, but you are thinking. You’re completely inside the actors, but you’re also a viewer objectifying what you look at.

At one point you say the theatre belongs on some level to the actors. So why is there a director? What do you add to the process?

Well, you know, in a lot of cases, I don’t think a director is really needed. Do you know how directing began?

I don’t think so.

Well, there were groups of roving Italian players that were putting on plays in Italy in the 19th century. And they needed somebody to be a little more objective, so at a certain point one of the actors, generally later rather than sooner, would go out front and watch and just give his impressions. I have found that in general actors seem to know a lot more than directors do. I do think I’m needed; they wouldn’t be able to do it without me. But I think in a lot of productions the director is not essential—the actors left to themselves might do it better.

It’s quite different from film, in which you literally have another eye on the action.

Oh, absolutely. It’s why I’ve never really wanted to direct film myself. Sometimes people would say to me, “You’re so good at what you do. Why don’t you just get a cameraperson who’s good and do it together?” But my wife is a filmmaker, so I know how extraordinarily technical films are, and I have trouble putting a light bulb in a socket. Technology is not my thing. And in film the director is everything. I have to say, since I’ve done a lot of acting since My Dinner With André, with the exception of a handful of directors, like Scorsese and Peter Weir, most of the directors were just nuts, you know? I also think the actual art of directing can’t be taught. It’s a gift. You either get it or you don’t get it. And I could probably count on two hands, easily, the directors that I’ve seen in my lifetime who I really think of as directors.

You’re known for a practice of doing long rehearsals, like years long. Did you take this idea from troupes like the Berliner Ensemble? Not many companies do that.

No, very few do. I certainly saw the amazing results at the Berliner Ensemble of working for a long time. And I saw it with Grotowski. I had dinner once with Roger Corman, and he was saying, “I make a movie in two weeks, why the hell do you need all that time?” I think there’s a very practical reason for it, which is that when you approach a play, either as a director or as an actor, you can’t help but have preconceptions about what the play is and who the characters are. But if you’re dealing with Chekhov or Shawn, the plays have so many mysteries under the surface that you have to be able to get the stereotypes out of your head. And time will do that.

I just wonder if there’s a paradox there. One of the things people seem to value in live performance is spontaneity, surprise. Is there a danger that long rehearsals will deaden or drain these qualities?

No. A long rehearsal is like a long marriage or relationship, or a long therapy, right? You reach places where you literally get bored, and you think that there’s nothing else that can happen. “I should get out of therapy,” or, “I should get out of this marriage.” Boredom, to me, is generally a sign that there’s a big shark swimming under the water, and if you’re patient, the shark will rise to the surface. So if you can have the courage to see your way through the boredom until the new thing appears, you’ll have amazing surprises.

So how do you know when rehearsals have done their work and a play is ready to show?

I just know. There comes a point where I just can tell that anything fresh that’s going to come out of it will have to come out in front of the audience, and that there’s nothing more you can find in the rehearsal room. Although I have to add that I’ve done four productions of Beckett’s Endgame, and every time I returned to it I was a different André; I was older, I’d experienced more and gone through so much. The play changed. If I were to do Endgame today, it would be about the coronavirus.

Since you bring that up: In the book, which you of course wrote before our current moment, you compare the U.S. to the Weimar Republic—in decline and susceptible to fascism. I wonder, does it feel more or less like Weimar now that we’re all on lockdown and talking through computers?

Well, the coronavirus and what’s happened to us doesn’t make me think more that we’re in Weimar. We have a president who is a lunatic fool who will be responsible for the deaths of thousands of people, so for me, he’s not unlike Hitler. I didn’t think he should be impeached—I thought he should be brought before the court in the Hague and tried for crimes against humanity. Let me put it this way: I think that going through this on a global scale, we can’t come out on the other end and be the same. All of us are going to be different. If the whole world would realize that we’re a tiny planet and we have to come together and work together, that would be something very positive that came out of this.

We can hope, I suppose.

We have to hope. Somebody said to me, the two most important things are love and hope, but hope is more important. Of course, if Trump gets reelected, God forbid, then we’re in post-Weimar—we’re in Hitler times. I’ll be moving to Canada.

If they open the border! It’s weird to be talking this way. It’s surreal. I have another question the book made me think of: Do you think life is a work of art? And if so, who is the audience?

You know that quote that I have in the book by Erland Josephson? It’s the one where he said to me, “When I was young I went to great teachers to study the voice. Now, if I could, I would find a great teacher who could teach me how to step down to the footlights, and by just standing there, give to the audience a sense of illumination and hope.” I think that is really true now with what we’re going through. I think that a kind smile, a warm look, can be an enormous gift to people. When I was in Demolition Man, the makeup person said to me, “Oh my God, you’re one of the nicest human beings I’ve ever met.” And I said, “Why do you find that?” And she said, “Well, you should see what the other people I work with are like.” So I do think that all of us have the ability to be thoughtful and kind and to radiate that feeling that people.

Whenever I sniffed a fox, I jumped into the chase. I was always ready to follow my nose.

I just want to turn that same question around. So many interesting things have happened to you. You’re almost like—and I don’t mean this disparagingly—a Zelig figure. From your dad working with Trotsky to your family staying in a place owned by Thomas Mann, from Gregory Peck slugging you over a disagreement to your assisting Billie Holiday in her nightclub act, the book is like a panorama of 20th century history. Do you feel like you’re living in a story? And if so, who’s the author?

I don’t know. I mean, who the hell was responsible for giving me this amazing theatrical life? My part in that was, whenever I sniffed a fox, I jumped into the chase. I was always ready to follow my nose. Spalding Gray once said to me, “If by nature you’re a storyteller, if you just stand still in an aware state, the story will come to you.” But then there’s the whole question of determination, you know? I was determined to get a job at the Phoenix Theatre when I was a young man. So I went after it and I kept knocking on the doors, and I finally was offered a job as a stage manager. If I hadn’t been, I would have never had the experience I had with Billie Holiday. On the other hand, of course, there are amazing things that have just come into my life that I don’t seem to have had anything to do with.

There’s also the thing of following your gut. You pass a bookstore window, and, for some unknown reason, you like the cover of the book. You know nothing about the book. So you go in and buy the book and it could change your life.

You’re pretty honest in the book about the long periods where you felt like you were flailing. Now that we’re all on lockdown, I wonder if you have any words of wisdom from your times in the wilderness. What sustained you through your fallow period?

Faith, you know—a little bit of faith. My wife who passed away, Chiquita, she was very close to the earth. She said, “Great vegetables grow in manure.” So if you trust as an artist that you are always working—always, you can’t help it—you may go through those long periods, and then it will pay off because of all you’ve been thinking and feeling. I mention Eleanora Duse in the book, and her leaving the theatre for 12 years, which must’ve seemed like a tragedy to many theatregoers. All she did was garden. But when she came back, Strasberg, who saw her perform, said it wasn’t like watching a human being, it was watching beams of light.

We tend to judge those periods. I once was giving a lecture, and a woman in the Q & A said to me, “I have a writer’s block. I don’t know what to do about it.” And I said, “I don’t think there’s such a thing as writer’s block. I think if you’re a writer, you’re just taking your time and you’re in winter. But spring will come, summer will come.” And she wrote me a letter about a year later saying, “I’ve begun to write again. What you said made so much sense to me.”

Everyone, including my own parents, thought I was a washout. During those years and in spite of faith, I asked myself many times, “What the hell are you doing? Will you ever get back?” But you do. You know, nomads will spend years looking for an oasis that is uninhabited, and then they finally find it and they settle down. They live there, they grow dates on the date trees, they love being there. And then suddenly one day, maybe 12 or 15 years later, they all realize it’s time to leave what they know and go back into the desert knowing that all they’ll be doing is wandering in the desert looking for another oasis that looks exactly like the oasis they left. But they need to wander.

It’s a well worn debate, but I wanted to ask: You were steeped in Stanislavsky and studied “the method” with Strasberg, but you also revere Brecht and Grotowski. These have often been seen as separate or opposed—as naturalistic vs. presentational theatre, roughly speaking. Do you see these as two distinct traditions or in some way complementary?

You know, Grotowski is now recognized in Russia as the great disciple of Stanislavsky. And Brecht’s work as a director was as close to Strasberg’s work as you can imagine, except it was simpler. But it came from the same source. It’s like, you can get a painter like Picasso and another painter who looks diametrically opposed in their methods and what they create, but both of them wouldn’t be there without Cezanne. So our roots are in the same soil.

In the book you mention the different ways actors can arrive at comparable results. So would it be safe to say you don’t believe in an orthodoxy?

No, I absolutely do not. I think that’s where theatre schools can often be a problem, because many do teach—including Strasberg—that there is one way. And there just isn’t. The creative process is very mysterious.

I didn’t realize until I read the book how much regional theatre you did before you directed in New York: in Philadelphia, San Francisco, Los Angeles. What was it like working in the regions back in the 1950s and early ’60s?

You know, if you love to direct and be in the theatre the way I did, it didn’t matter where you did it. It was fun. It was great. It was exhilarating. The fact that New York critics and audiences were probably not seeing it didn’t really make much difference to me.

If you could think of a play that would speak to our moment right now, what would it be? I guess Endgame is one you mentioned, but is there another one you can think of right now?

Wallace Shawn’s Grasses of a Thousand Colors. That is the most relevant play to this period I think maybe anyone has written. Because I think this is part of climate change, this virus.

Since you mention Shawn, I have to ask you: Did you see Waiting for Guffman? And if so, did you get your own My Dinner With André action figure?

No—I don’t know how he got there before me, but Wally has them. That was a wonderful surprise. I had a lady friend at the time, and it wasn’t working too well with her. We went to that movie and had a kind of unpleasant disagreement. But when I saw that bit at the end it just put me into such a good mood.

This conversation has done that for me, so thank you. It’s such a hard time.

I would say that part of what’s so difficult about this time that’s a little different perhaps from others… I think childhood trauma lives in the body and never really leaves you. And this is a reliving of 1938 and 1939 for me. Because this is a threat to all of us. So the germs that I can’t see are dressed like Nazi storm troopers, and all the panic that I felt back then—you know, the helplessness, the confusion, my parents not knowing which country to go to, where to sleep, whether it was time to leave with friends or should they wait? The knowledge that as Jews we would be in terrible trouble if we made the wrong decision. All of that is activated again in my body.

For instance, the other day, to my horror, I had to leave my place and go down to a gallery which is going to be showing my paintings, because the Times wanted to photograph me. The whole thing of leaving the safety of my place, all of that was quite frightening. And walking through the streets was unspeakably sad, you know, seeing the fleet of taxis driving around aimlessly and empty and knowing that those poor guys would be out of their jobs. So in any case, I am hoping I can get rid of this trauma with the little time I have left.

That’s a heavy note to end on.

Well, rather than end on a heavy note, let me say: Keep smiling. As my Gurumayi said: “Everything is funny.” She said, “Even death is funny; I’ve met him.” Just as women can’t remember the pain of childbirth, we will get through this and have some great stories. Some sad stories too.

You know, one story that isn’t in the book: When the Becks [Julian Beck and Judith Malina] were finally able to get back to America after their exile in Brazil, they hadn’t seen My Dinner With André, so I screened it for them. And afterwards we went to Julian’s loft and passed around this large bowl of marijuana. Judith was taking out the seeds. Each time it came to Julian he would pass, and I finally said, “Why aren’t you partaking?” He was already very ill by that time, and he said, “The Angel of Death could appear at any moment, and I don’t want to be stoned when he does.”