A husband and wife in their 80s bicker in a small house, arguing about the furniture placement in the assisted living cottage they’re about to move into. Their banter is ditzy and witty but sometimes sharp. Their daughter Laurel comes to the door with food from a farmers market, and tells them to wash everything carefully. She delicately tells them that maybe, just maybe, the virus may delay their move into their cottage. There’s a moment when you see her avoid a hug.

A husband and wife in their 80s bicker in a small house, arguing about the furniture placement in the assisted living cottage they’re about to move into. Their banter is ditzy and witty but sometimes sharp. Their daughter Laurel comes to the door with food from a farmers market, and tells them to wash everything carefully. She delicately tells them that maybe, just maybe, the virus may delay their move into their cottage. There’s a moment when you see her avoid a hug.

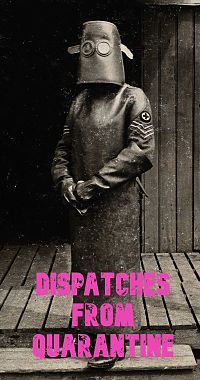

Things are odd and a little skewed but overall, it seems like a witty dysfunctional family dramedy. But as the play goes on, with each visit, the daughter’s costume gets more absurdist and extreme. The second visit, gloves and a face mask; the third visit, a hazmat suit. The aging parents aren’t allowed to leave, caught in an existential limbo: Is this living or dying?

The Ionesco-influenced play came to me very quickly, which sometimes happens. It came to me so quickly because I’ve been living it. My parents had been lured to California by warm temperatures and young grandchildren—and two years ago, they bought a house. My husband and two kids live in the main house and my parents live in what used to be the garage, now a well-appointed guest house. But my parents are planners, and the move West was just the first step toward a lush paradise, Mt. San Antonio Gardens, a retirement community where my mother could still garden but they would have a social life. They finally got off the waiting list—a celebration!—and were supposed to move in in late April.

And then there was a pandemic.

I had to convince them not to go shopping on one of the last days of somewhat normal life, before the stay-at-home order. My mother insisted they go at 10 o’clock, when it’s slow. I was able to keep them from going and sent them pictures from the grocery store with empty shelves and the lines 20 people deep—people already wearing gloves and face masks.

Then my husband told me he had a sore throat. So I dug out a pair of gloves and I still visited but followed all of the rules of social distance. (He never developed a fever, so we think it’s just a badly timed generic sickness.) I haven’t gone there in a hazmat suit yet.

My father offhandedly said to me, “It’s unsettling to hear people argue whether you’re disposable or not.” There are politicians and pundits saying that grandparents should sacrifice themselves on the altar of the economy. As we’ve been squabbling over the economics of the pandemic, weighing lives of people against the lives of corporations, there are real people at risk reading those op-eds and watching those press conferences. The reality is, I still have to interact with the outside world. Every time I visit my parents, I could infect them with a virus that could kill them without even realizing I’m a carrier. But I think human interaction is vital for all of us, so I risk it.

There’s the no less abstract question of whether theatre is disposable, as Nikki Haley flips out on Twitter because the stimulus package included money for the National Endowment for the Arts and arts organizations. What non-artists often don’t realize is that theatre has value to the economy. Most people understand that Broadway is an essential part of the economy of New York, with the theatre overall contributing $43 million to the economy of New York City. But the Commonweal Theater, for instance, is no less a part of the economy of Lanesboro, Minn., population 732. Just as my parents are not disposable, neither is theatre.

And this play that I’m writing: Is it disposable?

I’ve written plays that never got produced before. I assume every playwright has created characters who now roam in their imagination like disgruntled ghosts. And as a professional playwright, I’m aware of the standards of the contemporary theatre: simple sets, not too many characters. (My most successful play, Rich Girl, had four actors and one main set.) Topical but not too topical, because your play might get dated if it’s too relevant.

So what is my game in writing this play about my parents? Even if we all make it through this—even if in a year, theatre somewhat makes a comeback—everyone already lived this quarantine. Who would have any interest in revisiting it? (I’ve avoided all plays about 9/11 except for the one my own theatre company produced.) If my parents were to die because of this virus, would I ever want to revisit this play anyway?

On some level, I realize this play may merely become a family document. A reporting of my parents’ experience and mine. A true “memory play”—a memorial of my parents for their grandchildren, who hopefully will just have a vague memory of this time. I’m hoping my children won’t have this time emblazoned on their brain as “the time that Trump killed their grandparents,” but as a strange period where their parents struggled to homeschool them, they couldn’t get the Froot Loops they wanted, and they watched a lot of movies. Hopefully we all make it through and we can all sit together at Thanksgiving. Hopefully, this play is tucked away in some notebook somewhere to be found by my children, and they’ll say, “Oh wow, remember that?” and they have a love for live theatre that their parents and grandparents instilled in them.

It’ll have been lived once, written once. It’ll be language, story, words. The origins of theatre were initially an act of memory. I’ll be happy to have this play be merely that.

Victoria Stewart’s plays include Rich Girl, Hardball, and 800 Words: The Transmigration of Philip K. Dick.