Playwright Mart Crowley, best known for writing the path-breaking play The Boys in the Band, died on March 7. He was 84.

I arrived at the Catholic University of America’s drama department in Washington, D.C., in 1956, fresh out of the U.S. Army and a job in a California fruit cannery. I had a work scholarship for a Master’s degree in playwriting. I had lately begun to call myself an actor, which—when you’re not sure of either your talent or ability—was a daring thing to do. I had no money, wore my old Army jacket, sweater, and shoes, and was probably the first “beatnik” to show up on that august campus.

There I met a young kid—a reed-thin, slender boy named Mart Crowley. He was studying theatre as an undergraduate. He dressed like a preppy, very neatly, and he had a soft Southern drawl, which I recognized, as I come from Arkansas. That was the tiny bond that began a lifelong friendship. I was a loner. Mart seemed to be too, but he had a small circle of friends who were the campus “odd men out” in that day and time (other students whispered about “the queers”). I didn’t like the kind of talk that excluded people or groups from being human and turned them into objects of fear or derision or hate. I had no fear of the “Others” of life. I don’t know why I was different about that. Maybe it was a childhood rooted in Catholic teaching about Jesus, or maybe because my parents, ordinary blue-collar workers, never, to my knowledge, discriminated that way.

I wrote a play for a thesis, got my degree, and went to work with the school’s company of actors, Players, Inc., who toured the country playing the classic plays from history. Mart plodded on toward his undergraduate degree. It was summer between tours and I was visiting my aunt in Arkansas, and I got a call from Mart, who was home in Mississippi with his parents. He asked if he could come up and visit me. I picked hm up at the airport and we spent three days hanging out, driving around town in my aunt’s car, and talking. We were sitting watching the water moccasins slide by in the greasy creek by the railroad tracks (yes, like a scene from a Tennessee Williams play), and I was telling him about my dysfunctional family, when Mart pushed himself up close to me, and blurted, “You have no idea how bad things are!” He told me his mother was a dope addict and his father a violent alcoholic, and that he had had to deal with this his whole life. He loved them both but couldn’t take it anymore.

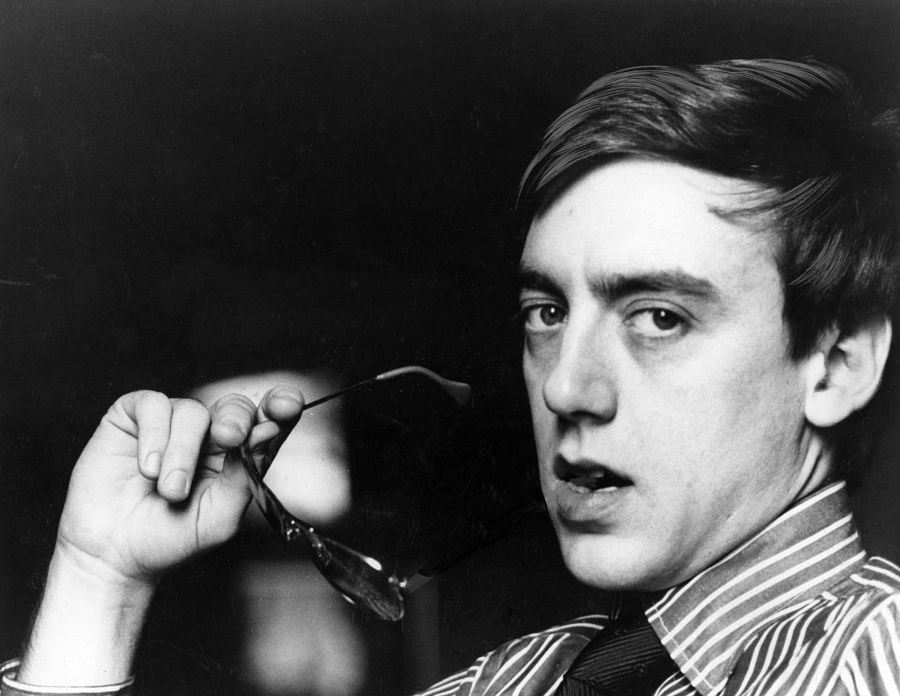

Then he cried, stopped himself, and said something bitter and funny that I don’t remember. I thought: This kid is tougher than he looks. He turned to me with his big eyes, made bigger by his eyeglasses, and didn’t say anything—just looked into my eyes. A moment passed. I knew he needed help—but the look was more than that, much more. I couldn’t respond in the way he might have wished.

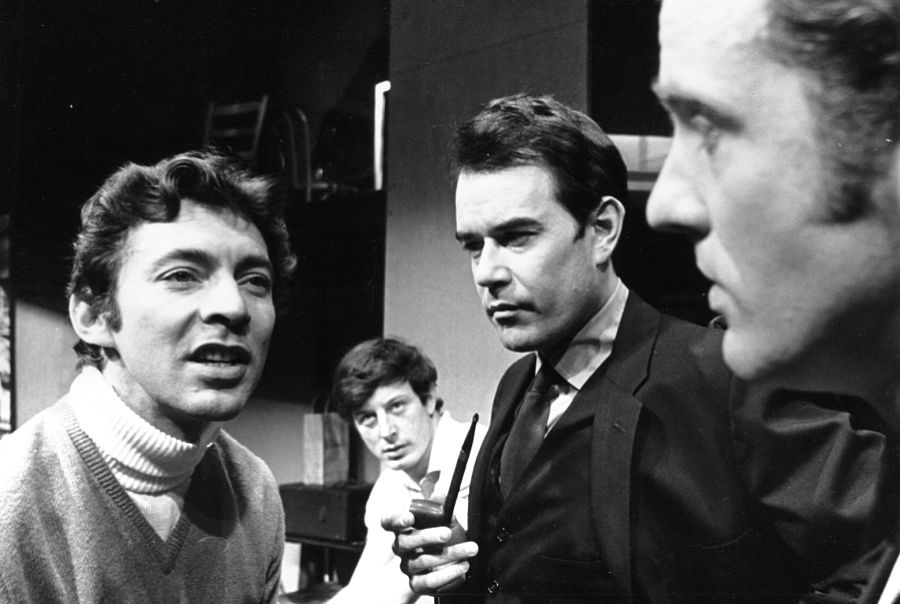

A decade passed. I heard Mart had gone to Hollywood. I was in New York, making rounds, working my way slowly up the theatrical ladder, finally getting small recognition: a Broadway tour, a Broadway flop, a Critics Circle-winning Off-Off-Broadway show, summer work in Shakespeare with John Lithgow’s father, Arthur, a soap opera—my first regular money from acting. I got a call from Mart: Would I read a play he’d written? Yes. I picked up the play from a tiny, grungy downtown theatre out of any known theatre circuit. I read it. Mart asked to meet the next day. He was clutching the play to his breast like a baby. He had been asking, begging, actors and directors and producers to just read it, and getting no response or much worse. But there was to be a very small no-pay production funded by Edward Albee’s producing unit. Mart looked at me again, as he had before—hoping, and ready to be turned down. I said, “Mart, I’ll do it.” Again, there were almost tears, quickly wiped away.

The play was The Boys in the Band.

I was told it would destroy my budding career to be identified as a gay man. I didn’t care. I did the play and the part offered because Mart was my friend. It was a hit Off-Broadway and ran three years. Mart got offers from Hollywood to make the movie, but was told that would happen only if the nine “faggots” in the cast were replaced by movie stars (never mind that two of us in the cast were straight, and “faggots” was an ignorant, shitty word). Mart refused. He insisted the play would only be a film if the original cast reprised their roles. None of us were movie stars. I had done television in New York but never a movie.

The movie got made and each of us got a chance to shine. In my case, it worked—I went on to have a television and movie career. My “courage” in risking my “career” was nothing to me—just something I had to do for my friend. Mart was a tough guy. A courageous man. A hero. A prescient man. The play had torn open the closet door that had imprisoned men and women of a different sexual orientation. The play became a stellar moment of social justice which justified to me my whole impetus and insistence on being an actor. It was 1967 when we began the journey of the play, which we felt as an extension of the Civil Rights Movement, which is still being fought. A year after we opened, gay men fought back against the police at Stonewall Inn in New York City.

Mart had broken through his life of failure up to that point and was free to build a career writing. He was also, by then, an alcoholic, like the character Michael in the play. He knew it and struggled with it. He had struggled with homosexuality and rejection of it, and had yet to really come to terms with it. Always we had been friends, and the play had made us better, deeper friends. Almost every night after the show, the “boys” of the cast went to “the baths” in the city—places to pick up strangers and have sex indiscriminately. By the late 1980s, most of my former cast mates were dead of HIV/AIDS, and by the ’90s all of the actors and crew—even the producers—were gone, their lives snuffed out by an animal-borne disease that was called the “gay disease” until that was disproved when it spread to the population at large. HIV is just one in a string of viruses that plague humans to this day.

Mart got sober and continued writing. He asked me to participate in two of his subsequent plays, but they weren’t right for me, so I declined. Neither fared well. I always liked his work, and was disappointed for him when he didn’t follow Boys with other successes. We met often by then, talked about our lives as we always had—me about my own family, which by now included five children, and Mart about men he had loved, what he was working on now, about happiness—how to get it and hold on to it. He was a very smart man about the theatre, and we argued when I told him I was sick of acting and its difficulties. It hurt him to hear that. When I said I wanted to quit the whole game, he tried really hard to talk me out of it. It helped.

To me, he still felt like a younger brother, even though he was tougher than I and had a brilliant, analytical mind. He told me what he had endured as a very young child, and how all through adolescence and young adulthood he had been abused—first by a Catholic priest at school, and later within his family. I let him know that I had been abused by an older man when I was 17. I then confessed to Mart that if I could have ever loved a man sexually, it would have been him. It was a simple truth that came out of many years of mutual respect and friendship. There was a long, long silence. He said, “I think I’ll die now.”

That was many years ago. A few years ago there was been a 50th-anniversary revival of the play, this time on Broadway. A Netflix film has been made of that production, both directed by the best man for any theatre job, Joe Mantello. The only thing missing from the revival was “the closet,” with all its stifling fear. It’s a new day. At the New York opening of the play, I got to say to the press what I felt after all that time: that Mart and the original gay cast were the heroes. The gay men of that cast, and Mart, had all risked much more than I had—they came out to the world at a time when the world was still poisonous for gay folk. Maybe I risked my “career,” but they risked their lives. There were only three of us still alive at that moment: Mart, Peter White, and I.

Before the Tony Awards that year, Mart called me. He was trying to come up with an acceptance speech if the play won. He wanted to know how it had been for us, the original “boys.” We talked for two hours—then he told me he had been taking notes on all I said. Then I wrote him an email recapping what I knew about all of us that he had not known. The play won Best Revival, and I saw his speech well after he made it. It was very moving. He gave all the credit to us—to the original cast—the people, he said, who were the reason he was now standing on the Radio City Music Hall stage and accepting an award for a play he wrote in desperation when he was dead broke but had never despaired of getting a hearing for. Heroic. Generous. True Mart.

So many lives have been changed by the play. Almost every day, a man here where I live in Palm Springs tells me how seeing the play gave him hope. Some say I showed them how they could safely come out. I tell them it was the man that Mart wrote, not me.

Mart is gone now—to Spirit. “Ave atque vale,” as the Romans said—“hail and farewell.” I am at the age when friends leave quickly and quietly. Mart’s heart had been a problem for 20 years or more, and finally, it simply said: Martino, it’s time. Hamlet said, “It will come when it will come–the readiness is all.” I know Mart was ready. He was a tough guy. I miss his presence in this life—the gentle, funny, brilliant little brother. I asked him once why he thought he was still alive when everyone else had gone too soon. He said simply, “I never liked anal sex that much.”

I remember a saying on a tombstone in an Ozark graveyard that I’ve kept in my heart all my life for my family: “Another link is broken in the household band / But a chain is forming in a better land.” The last moment in my favorite play of his, A Breeze From the Gult, comes when the character of his mother, Lorraine—dying of drugs—says to her son, also named Michael (as in Boys):

Let’s just sit here a moment with our eyes shut and pretend that a lovely breeze is blowin’ in off the Gulf. If we think about it, that’s where we spent our happiest moments. We only had moments of happiness—and they were always on the Gulf Coast—but they were enough to make up for a lifetime.

She sings, and he listens.

Goodbye, my friend. Go with the breeze from the Gulf. We will meet again.