This story is part of a special issue on theatre and climate change; the whole package is here.

The turning point was Katrina, as is so often the case when you’re asking questions in New Orleans, trying to get to the heart of the matter. A Studio in the Woods is located on a plot of land purchased by Lucianne and Joe Carmichael in 1969, comprising 7.66 acres of endangered forest in the Louisiana wetlands. Says Ama Rogan, NOLA native and the studio’s managing director, “These bottomland hardwood forests are what surround us in New Orleans. Not the cypress forest, but a little bit higher wetlands, because of the proximity to the river. They’re beautifully adapted to hurricanes, and an important part of the cycle.”

In fact, the mission of A Studio in the Woods, a uniquely situated artist residency half an hour outside of New Orleans’s city limits, is to protect and preserve those hardwood forests, and to “provide a tranquil haven where artists and scholars can reconnect with universal creative energy and work uninterrupted within this natural sanctuary.” As Rogan puts it, “Prior to Katrina we were hosting residencies for artists of all disciplines, but we didn’t have any kind of programmatic direction. The most significant way that [the residency has] changed came with the change that we all experienced post-Katrina. Immediately after Katrina, we hosted residencies for local artists coming back home, called ‘restoration residencies,’ and we gradually came to realize the importance of our place in a new way. We now invite artists to look at issues related to environment really broadly, with a community engagement aspect, through six-week residencies.”

The residency season at A Studio in the Woods runs from September to May, with applications opening every January for emerging and established artists of all disciplines. Residents are assigned private living and studio space and share communal facilities with other visiting artists. Artists are supported with a stipend, materials budget, and groceries.

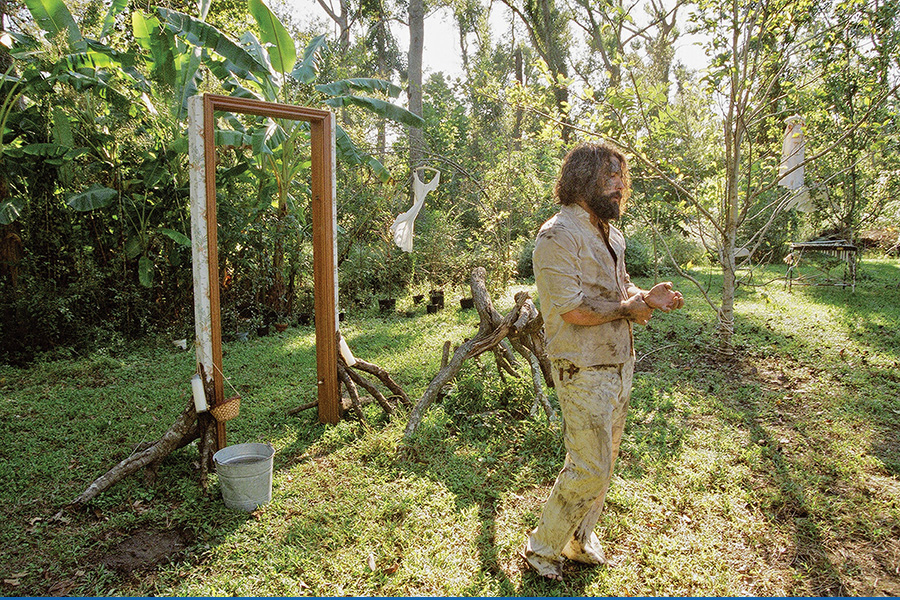

Among the many artists A Studio in the Woods has hosted since its inception in 2001, Kathy Randels, Nick Slie, and Hannah Pepper-Cunningham—all theatremakers based in New Orleans—are united in their creative participation in Cry You One, a monumental documentary theatre project exploring the interconnectedness of land and culture in Louisiana. Randels has been associated with the studio since before it became an official artist residency and presented Beneath the Strata/Disappearing, an original work by her company, ArtSpot Productions, there in 2006. In a post-Katrina world, Randels says, “It was a chance for us to have something to work on while we were also working on processing what the hell had happened to us with Katrina. I think our urgency to explore this material and tell this story together was very high, because we were talking about our home, and our home looked like it wasn’t going to survive.”

The relationship between the land and her artistic work has become increasingly obvious for Randels in the years since the catastrophic 2005 hurricane. In the development of Beneath the Strata/Disappearing, she recalls, “I was intrigued by how active the plant life was right after Katrina. There were watermelons blooming all over the city, and so many flowers were coming up out of the destruction, in strange places; the golf course was covered.” Around the studio, she noticed that “downed trees were there and decomposing, but stuff was growing up out of the trees. That was really amazing.” Randels says the studio’s resident botanist, Dave Baker, explained that “a hurricane is a blessing in a swamp, because it takes out a lot of the old trees and allows new growth space to build.”

Through myriad twists and turns, connections and outgrowths, Beneath the Strata/Disappearing became Part One of a Louisiana trilogy, which would go on to include Loup Garou in 2009, a solo performance by Nick Slie, and Cry You One in 2013. For these artists, the relationship between the land they live on and the work they produce is necessarily interconnected, as they live in an area vulnerable to climate change in a way that other parts of the world are not, exacerbated both by global warming and local human-made infrastructure and natural resource extraction. Says Randels, “Louisiana is one of the ground zeroes of climate change on the planet, climate justice, and environmental justice. We turned plantations into petrochemical plants, the descendants of the enslaved Africans still live, work, breathe in and have gotten cancer and other diseases from those places.” Historically, this land has been a battleground for dominance over resources and profits, and present challenges are informed by past infractions.

Nick Slie, another Louisiana native, traces ancestors in the region back to the early 1700s. Says Slie, “My people moved with the food, and they moved with the water. The delta system mirrors my own ancestry, which is something that is fluid, ever-changing, and ever-shifting. It’s how I’ve grown to understand who I am, as a person, by a deep investigation of the landscape here. I’m moved artistically as well by the mystery and the unknown of this land.” Like Randels, Slie’s artistic practice is deeply rooted in the place he calls home. Says Slie, “I don’t know if I could do what I do if there wasn’t a New Orleans. I never dreamed of living in a place that I thought of as my ancestral, my spiritual, and my artistic home, and I feel extremely blessed for that to be the case.”

Hannah Pepper-Cunningham, unlike Randels and Slie, is not native to the region, having grown up in Massachusetts, and has instead developed their emotional attachment to the area over the past 10 years of living and working there. They acknowledge that there is a difference in witnessing the grief of climate change in a place you’re from vs. a place to which you’ve relocated. In fact, they confess, they’ve never felt a tight native connection to any particular place, as their family has never lived in one place for more than a generation. Working on Cry You One, though, allowed Pepper-Cunningham to establish an emotional connection with their new home, “almost like a directed study in coming to have a relationship with a certain land,” they say. It also forced them to reconsider the distinction we make, linguistically and socially, between “land” and “environment,” and the remove with which urban dwellers tend to regard the land on which they live.

The notion of witnessing is a recurring theme in these three theatremakers’ practice, as each seeks to reconcile their role within the ecosystem of our contemporary social and environmental landscape. Each of them emphasizes the importance of intersectionality in considering the impact of and solutions to climate change. Indeed all three explained how, through their research and personal experience, they’ve observed that climate justice is integrally intertwined with structural racism, and that Indigenous communities and communities of color are disproportionately negatively affected by racist climate policy. In a state still living the consequences of its history of slavery, Slie says, “The same forces that are responsible for coastal land loss are responsible for inner-city land loss [like we’ve seen through the gentrification of New Orleans]: patriarchy, domination behavior, white supremacy, wholesale environmental capitalism, and wholesale environmental destruction.” A Studio in the Woods itself is situated on land that was formerly a plantation. Rogan says, “The land still has its scars, like ditches that were made for agriculture.”n

Pepper-Cunningham cites the importance of “just transition,” a key idea she explored in her residency at A Studio in the Woods, and its relationship to abolitionist practice, as well as “how heteronormativity and the structures of the nuclear family limit our ability to respond to climate change.” Citing the work of Movement Generation, Pepper-Cunningham describes “just transition” as the process of moving from extractive economies to economies rooted in justice and sustainability for all. They credit Jayeesha Dutta, one of the leaders of Another Gulf Is Possible, for her inclusion of the notion of “just transition” in the development of Cry You One.

Cry You One, born of a dream of Slie’s, conjured a sort of a jazz funeral for southern Louisiana, and, in the tradition of a New Orleans funeral, yielded equal parts solemnity and celebration. It metamorphosed into a guided experience for audience members exploring various “solutions” to climate change without offering any specific fixes, instead offering a myriad of ideas, opinions, and encouragement to pursue action. Though deeply entrenched in the specifics of the southern Louisiana landscape, Cry You One toured the United States and internationally (including a run in Serbia), connecting with audiences by lightly adapting the script to address local issues and relying on the universality of deep specificity.

“Water is just water,” Slie explains. “In the desert there are water issues, on top of the mountains in Kentucky there are water issues, there are crazy water issues on the Eastern seaboard—more hurricanes there, in many ways, than we’ve seen in recent years down here. So I think it was a constant experience in finding that the story’s the same.”

Of course there’s no single solution to achieve the radical dismantling of the complex network of oppressive systems that have led us to our current reality. It’s all connected, and we have a lot of “cleanup” work to do, according to Randels, on “spiritual, psychological, physical” levels, all of it “stemming from the wounds of genocide of the Indigenous people and slavery. And we must have the people who have been most harmed be the leaders of the movements, because they are the experts.” Slie agrees that we must look to communities led by Indigenous people and people of color for new solutions to these inherited problems, saying, “We’re definitely facing down this idea that it might not be possible for us to live here, and I’m particularly interested in what type of behaviors, what type of wisdom, what type of secrets, we can learn in this time.”

New Orleans carries a certain mystique, but that shouldn’t overshadow the serious work of the artists and organizers striving toward a more equitable, just, and sustainable future. Slie says, “I believe that this place is born on a type of difference, a type of fluidity, a type of movement, a type of flow, that creates the opportunity for a lot of people to engage with the magic here. I think this place is also born in a lot of pain, and a lot of suffering, and a lot of struggle, and I think that we can never forget that—that it is born also out of an act of violence.

“At this point, at least with regards to the river system and the wetlands, it’s being held together by many acts of violence, so there’s this tension between precision and mystery here, at all times,” Slie continues. “There’s the precision of the artificial circumstances it takes for us to even still be living here, and there’s the mystery of how we continue to be confounded by what this landscape, this water, will do whenever it wants to do. That, to me, creates the perfect conditions for artwork. And for creativity.”

Words like resistance and resilience are frequently tossed out, particularly in regard to the struggles faced by Indigenous communities and communities of color in Louisiana. But the artists I spoke to find those terms overused and imprecise, preferring instead to invoke notions of grief and death. To embrace the natural life cycle, including death, it is essential to slow down and observe the rhythms of the earth, something a residency at A Studio in the Woods can offer ample time and space for. Slie says he’s interested in “laying the groundwork for people to use things like grief, and sadness, and slowness, as a wisdom,” and is currently participating in his first residency at A Studio in the Woods to explore a new project about the Mississippi River, his ancestry, and loved ones he’s lost on the river.

In our fast-paced digital age, it is increasingly challenging to shut off external stimuli and simply observe the natural world. Rogan says that at A Studio in the Woods, “All the artists have a chance to go into the woods and understand where they are in a deeper way and how it relates to larger ecology. It’s an important way of becoming grounded in where you are. If you’re untethered, it’s hard to be creative.”

For those avoiding the confrontation of climate change as a reality, Pepper-Cunningham says, “It’s not any less threatening if you don’t look at it squarely on. Making space for grief, and holding your own pain, can be a reason that can prevent people from coming toward it, because you have to acknowledge how big the problem is, and how bleak the situation is. But there can also be something really liberating; the internal tension you have to hold up in denial is exhausting. There’s something liberating about being honest about what’s happening and reconsidering what a meaningful life is.”

As New Orleanians know well, despite best-laid plans, we humans are ultimately powerless against the forces of nature. With that backdrop, artistic examination and interpretation of our natural world becomes even more vital as we question the human-made systems that attempt to alter it. The opportunity to slow down, sit in the woods, and contemplate, all in the service of transformative art and community engagement, is precious. As Rogan says, “The soil is young, and the river is powerful, and it’s just a cauldron, in that way.”

It’s up to us, as artists on the front lines of a changing world, to figure out how to best harness that power. The future depends on it.

New Orleans-based writer, translator, and theatremaker Amelia Parenteau is a frequent contributor to this magazine.

Creative credits for photos: Beneath the Strata/Disappearing. Created by director Kathy Randels, visual artist Asante Salaam, performers Ausettua Amor Amenkum, Aja Becker, Herreast Harrison, Stephanie McKee, Lisa Shattuck, Beverly Trask, and Nick Slie, with musicians Sean LaRocca, Luther Gray, and Jonno Frishberg. A Mondo Bizarro and ArtSpot Productions performance, part of event series Antenna::Signals.

CORRECTIONS: Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this story misgendered Hannah Pepper-Cunningham, whose pronouns are they/them/theirs, not she/her/hers. Also, the artist’s last name is Pepper-Cunningham, not Cunningham. In addition, the piece inaccurately stated that A Studio in the Woods residents are responsible for their own groceries; the residency includes reimbursement for those expenses.