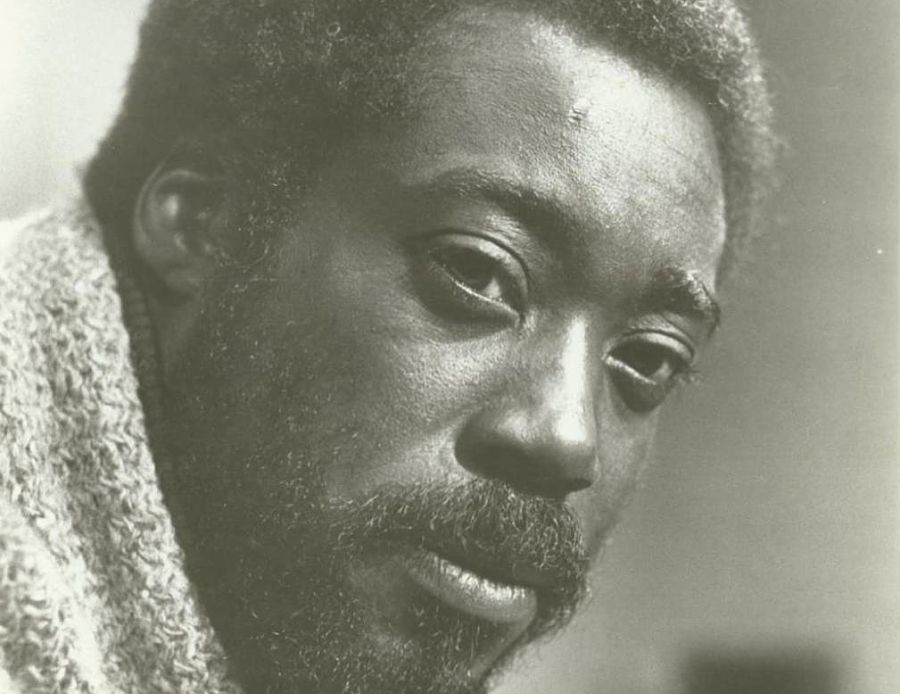

With Roundabout Theatre Company’s Broadway revival of A Soldier’s Play now in previews, I took the opportunity recently to speak with its author, playwright, screenwriter, and novelist Charles Fuller, who won the 1982 Pulitzer for the play, later adapted into the film A Soldier’s Story. Among Fuller’s other notable plays are The Perfect Party (1969), In the Deepest Part of Sleep (1974), Zooman and the Sign (1980), and One Night (2013), dramatizing topics ranging from racial tensions among a group of mixed-race couples to violence in Black neighborhoods to sexual assault in the armed forces. A native Philadelphian, he now calls Toronto home (his wife is Canadian, he explained).

NATHANIEL G. NESMITH: You have been involved in theatre now for more than five decades. What first drew you to it?

CHARLES FULLER: It was the immediacy of it. You can sit in the theatre and watch what you wrote and know that it is either terrible or operating in the way you want it to. You can’t do that with anything else. If you write a book, you have to wait for people to tell you that it was good. Or if you write an essay, you have to have the editors tell you everything is fine. The theatre is a place where immediately you know that it is working or it is not. People will start shifting themselves in the seats or scratching or turning towards each other whispering. For me, the theatre is an immediate scale; it is either good or it is terrible, or it is working. It is not always wonderful the way you thought it would be, but you get right away if the audience is with you or not.

Many of your plays have drawn extensively on historical research: The Brownsville Raid, the We Plays (Sally, Prince, Jonquil, and Burner’s Frolic), and, of course, A Soldier’s Play. Do you feel a different ethical responsibility when dramatizing historical content?

I do that because I like to look at the history from our point of view. Nine times out of 10, our history is written by people who are not Black. What my feelings were when I began to write plays was that I would try my best to bring out all the things that had happened and try to let them happen on the stage so my audience would be hearing this and watching this from someone whose history was a part of it, in a very real way. One thing to doing history, from my point of view, is really trying to get on with what happened, what the situation was at the time that those things occurred.

Who are the writers that influenced you?

In terms of plays: Arthur Miller. In the theatre: Amiri Baraka. I liked what he was doing. [Also] the people who look at the world they are in and connect that world with Black people. Baldwin, Ellison—those are writers whose works I really enjoyed. What I read the most are things that connect African Americans to the history of the world; that is one of the things that drives me to continue writing.

Which of your plays do you admire most, and why?

I like them all, really, because in each one I am trying something different, a different space, a different place, a different way of looking at things, creating characters I have not dealt with before. Each one is new, and for me, the work isn’t of great value if I keep doing the same thing all the time. I do history because there is so much of it that we are involved in, and we have not looked at that portion of our history in this country. I try to pick up things that I care to deal with—that are connected to the United States, and to us. I am always confident when I look back on my own life because I was in the Army—I gave time from my life to the United States. I look at that and go back to that time whenever I start writing.

A Soldier’s Play, which explores racism and intra-racism, is tightly constructed. Did you think a great deal about its structure while you were writing it?

To be honest with you, the structure comes as I work. I always tried to do things that I have not seen on the stage or in a play I’ve read. I try to do new things, different things, so that the audience is not tired of watching the same old thing every time I do something.

You have stated that A Soldier’s Play was written not only to show the importance of Black soldiers and officers playing a role in the changes in America that would occur during the 1950s and ’60s; it was also written also as a memorial for your friend, the poet/playwright/writer Larry Neal. We don’t hear about Larry Neal anymore. What would you like to share about him?

He and I grew up together. We lived in the projects. I lived in 2605F and he lived in 2605K in the James Weldon Johnson Project in North Philadelphia. We were buddies as we grew up, long before we were thinking about writing. We were in the same class in the Catholic school we went to. Larry was left back after the first grade, and I came into the school and he was supposed to go to the second grade, but he didn’t. When I was in the first grade, he was in the first grade with me. We were close friends until he died. Larry was a good writer, and he was always someone who was concerned about the history of African Americans, and so when we started thinking about being writers, it was part of what we talked about a lot. Larry was the person who introduced me to Ralph Ellison.

Many, many years ago I saw a reading of your play Life, Death (A Dance), about men in the cardiac ward of a hospital. I always thought that I would see a production of that play. What happened to it?

That’s done. It’s over. As far as I am concerned, it’s finished. I might get back to it, but I don’t think I will. Once it is over, it is over. I don’t have an interest in going back to redoing it.

Why did it never have a production? It was a very interesting play.

No one wanted to do it.

I know that Douglas Turner Ward and the Negro Ensemble Company were significant in your career as a playwright. How did that relationship begin?

I met Douglas Turner Ward in a small restaurant on Second Avenue. I was in New York and I had another play, The Perfect Party. I had gone to New York to meet the people who were producing that. When we finished the meeting, I walked into this small restaurant and there was Doug sitting at the bar. And I said, “Are you Mr. Douglas Turner Ward?” He said, “Yeah, sit down and have a seat.” We talked. He said he had heard about The Perfect Party and he asked if I would be interested in sending my plays to the Negro Ensemble Company. I said, “Yeah, I would love that.” From that day to this one, we have been close friends. He helped my life and hopefully I helped the life of the Negro Ensemble Company.

He then directed the original Soldier’s Play. Do you think that without his guidance and support that your play would have received the attention it did?

I don’t know. Working with Doug was one of the most wonderful things I have ever done. He is a person who loves the theatre, supports his writers. At the time the NEC was moving, the play came to it. He was always supportive and a good director. He taught me a few things: Focus on the No. 1 person in the play. He helped me understand the stage better—what can I do and what can’t I do. I can’t put WWII on, say, a 34-foot stage and expect people to understand all that’s going on. I have to think about the time of the play. What am I trying to do? Doug taught me a lot of things like that that were really salt-and-pepper things, because it was right there on the stage, and you have to think about all of these things when you are writing the play.

The play traces the downfall of the character Tech/Sergeant Vernon C. Waters. What was goal in writing this character?

Part of my life I grew up in the projects, like so many Blacks, and there were always people who talked about how much better they would be if they were not in the projects. People in the projects didn’t do this! People in the projects didn’t do that! People in the projects were dumb! People in the projects were all kind of horrible things! Sergeant Waters was a character I saw a lot of when I lived in the projects—someone who wanted to be a king in a place that didn’t need a king. He thought that he would be very important if he walked away from the people in the projects and pretended to be someone else.

Captain Richard Davenport delivers a key line in A Soldier’s Play: “You’ll have to get used to Black people being in charge.” What more can you tell us about that famous line?

Well, it is as clear as it can be.

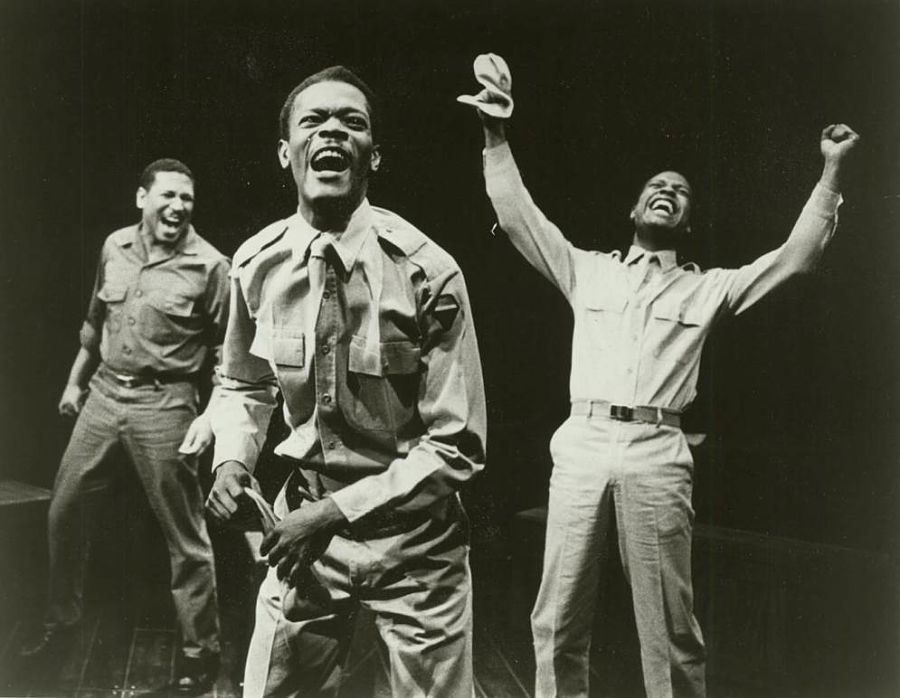

That original Off-Broadway production featured Denzel Washington, Adolph Caesar, Samuel L. Jackson, Charles Brown, Larry Riley, and the 2005 Off-Broadway revival, directed by Jo Bonney, featured Taye Diggs, James McDaniel, Anthony Mackie, Steven Pasquale. The new Roundabout production has Kenny Leon as director and stars Blair Underwood, David Alan Grier, and Nnamdi Asomugha. Do you have any thoughts about the new cast?

I will be honest, I know David Alan Grier, but I don’t know the other people. I am not worried about it. The play stands out. It always works. I think they are going to do a good job. Kenny Leon is a good director. They will put it together and make it something that the audience will enjoy.

How did this recent production of the play come about, and did you have any involvement in it?

No, not at all. I heard from my agent in New York that the Roundabout Theatre Company wanted to do it. I had nothing to do with it, except that the people in my family want tickets all the time. I met Mr. Leon and we talked here in Toronto. The play works. One of the things that Arthur Miller said to me was, “If it works, it works.”

You might be the first African American playwright who has ever had three major productions of the same play in Manhattan. If this is true, and I think it is, how do you feel about this? Also, what was the significance of being the second African American to win the Pulitzer Prize for drama?

[Laughs.] I have to say something to you, I am sitting here and saying to myself, “Oh, really?” To be honest, I did not pay that kind of attention to it. I was delighted to have received the Pulitzer Prize; I feel very blessed to have it, but I have to go on and keep working.

It took almost four decades for A Soldier’s Play to arrive on Broadway. How do you feel about that?

Pretty good. I have never been a “must have a Broadway show” [writer]. To be honest, I never wanted to push that. I felt when I was working with Doug and [NEC] that somehow the work would be changed or something would happen to it on Broadway. I am delighted that it is on Broadway now, but in all the years I worked in New York, I honestly did not think about Broadway. What I thought about was: How do we make plays about African Americans that people in this country will pay attention to, will listen to, hear what is inside of us? That is what drives me; Broadway does not drive me. What always drives my work is: Is it real? Is it important for our people? And if it is, I am successful. If it is not, I wasted everybody’s time in the theatre.

This production aside, A Soldier’s Play is now in the canon of American dramatic literature. Do you think it will continue to resonate in the future?

I think people will do it forever. There are very few plays with Black men, and if there are, the Black men are always in a weak position: “Oh my goodness, we need to do this.” “We need to do that.” “We need to get ourselves together.” I did not want to do that. I wanted to do us as what we are. I was in the Army. I was not afraid of things when I was in the Army. Why should you be ashamed or be afraid of things when you are out of it? I had known so many Black guys in the war who were straight shooters, great people. I had no reason to walk around putting Black people down.

I never wanted to do things that suggested that we are somehow lesser human beings than anyone else. So what I always do is create what I believe are Black people who are real, who are not afraid of anybody, and who move forward with this country and are responsible in many ways for where the country goes. I have never had a fear of being a Black man.

Critic Frank Rich wrote of the original 1981 production that it was “a major breakthrough” and “in every way, a mature and accomplished work.” Did you have any inkling that the play would be so well received?

I don’t know. I don’t look back at A Soldier’s Play. It was wonderful research and I enjoyed doing it, but I am working on work right now that is very different from that.

So what can we expect next from you?

[Laughs.] I can’t tell you. I am working on it right now. It will be a surprise.

Two decades ago you told me, “As I get older, I am enjoying writing a great deal more.” Is that still true?

Absolutely! And I just turned 80. Can you imagine that?

I will end with something I also asked you two decades ago: What advice do you have for playwrights?

If you create a character that people believe is real, you have succeeded.