René Auberjonois, who died on Dec. 8 at the age of 79, was a man primarily of the stage. Certainly his long and robust career took him into film (from M*A*S*H to The Little Mermaid), TV (“Benson,” “Star Trek: Deep Space Nine,” “Boston Legal”), video games, and audiobooks, where he garnered popularity and fame. But from his youth, when John Houseman first advised his parents to send him to Carnegie Tech, he was a leading member of the great American company of players.

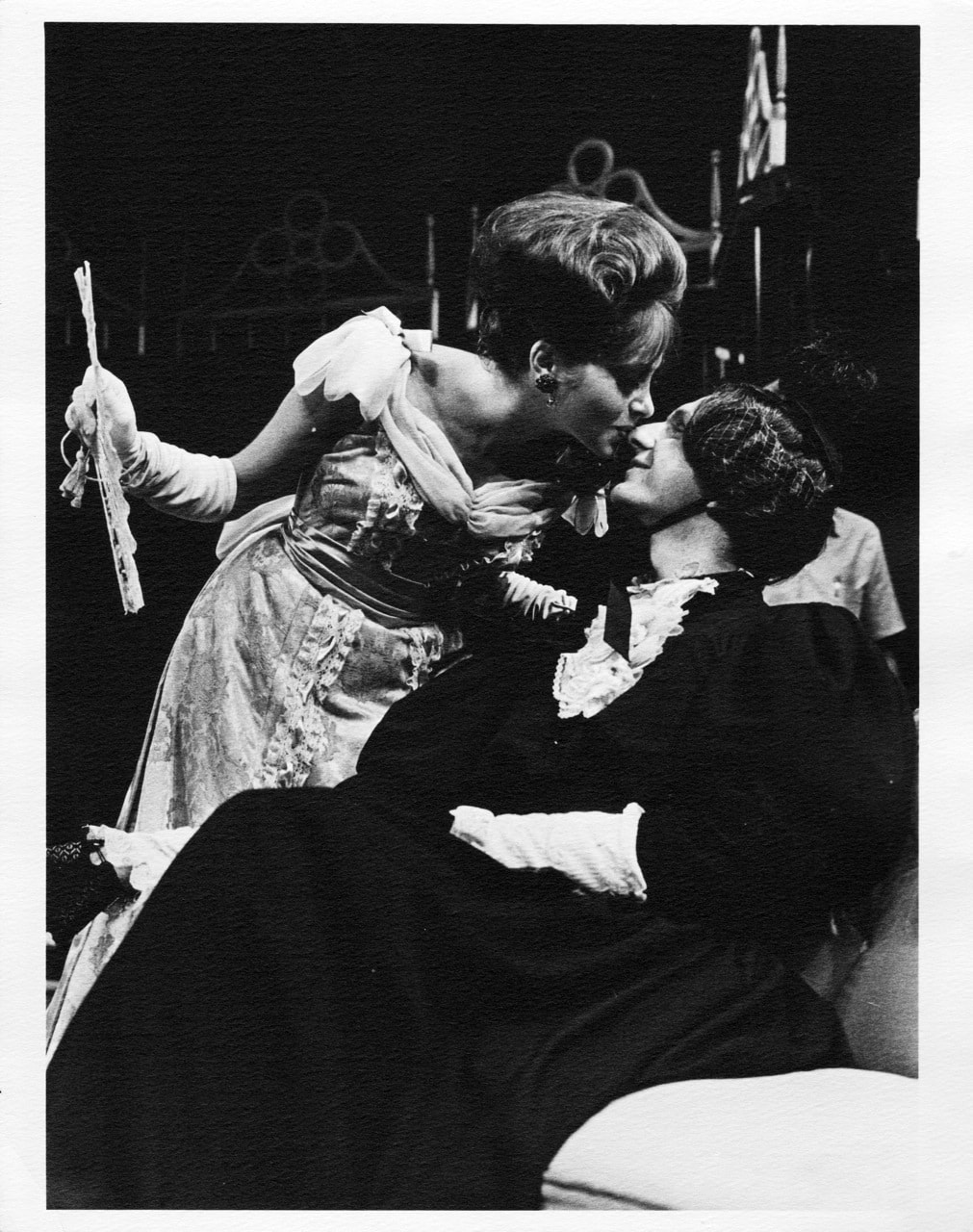

He was a founding actor in Bill Ball’s American Conservatory Theater, not just in San Francisco but in its ur-year in Pittsburgh, where he played Tartuffe and Lear—yes, Lear—at age 25. Later, as a member of the Repertory Theatre of Lincoln Center, he played the Fool to Lee J. Cobb’s Lear. Subsequent Broadway work earned him Tony recognition for Coco, The Good Doctor, Big River, and City of Angels. He was a man at home with greasepaint and footlights.

So it was supremely just that one night in November 2018, he found himself in the upper rotunda of Broadway’s Gershwin Theatre, where the walls are encrusted with raised gilt letters recording the several hundred members of the Theater Hall of Fame. Eight are added each year. Frank Langella was chosen to introduce him as one of that year’s inductees, along with Christine Baranski, David Henry Hwang, Maria Irene Fornés, Cicely Tyson, Adrienne Kennedy, James Houghton, and Joe Mantello.

After noting that he himself was already a member, Langella quoted Robert Edmond Jones’s invocation of actors, “who have in them a kind of wildness and exuberance” and for whom “to spend a life practicing and performing this art of speaking with tongues other than one’s own is to live as greatly as one can.” Langella cited “just a few of the tongues with which René has spoken over the last 50 years: William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, Anton Chekhov, Bernard Shaw, Samuel Beckett, Bertolt Brecht, Jean Anouilh, Molière, Harold Pinter—that’s just a few.

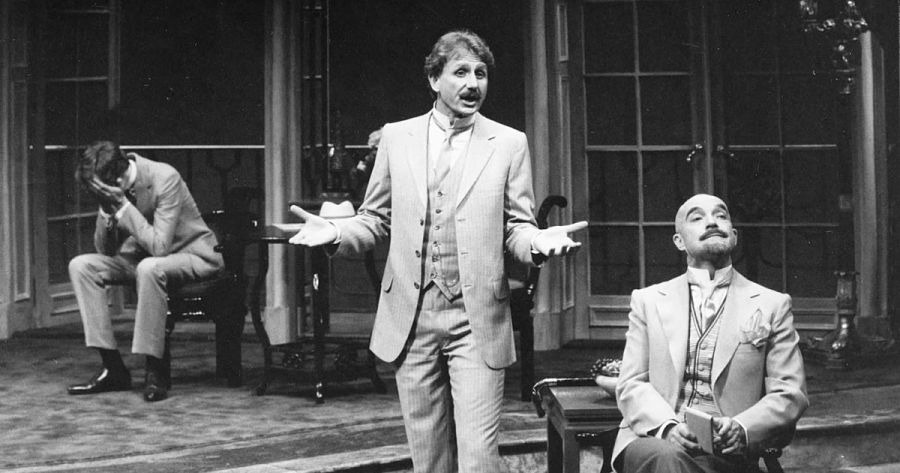

“To my great regret,” Langella continued, “René and I have not shared much time on the stage together, which I think is the secret of our long friendship. To watch my friend from the audience has always been a distinct pleasure…The last time I saw the miracle of René onstage was in Larry Gelbart’s Sly Fox. He was driving the audience apoplectic with laughter, playing a dirty old man prancing and prowling and stuttering with lust…The shaking, the spitting, the moaning, the tongue-darting excess, was just dazzling.”

Thus introduced, Auberjonois responded, “Maybe you could save that for my eulogy.” People laughed. But Langella’s praise evoked from Auberjonois an even greater eulogy: a paean of praise of the company of actors with whom he had joyously lived his life onstage.

He first cited the practice of beginning a yoga session with a recitation in Sanskrit, designed “to invoke all those who came before, the ones who’ve handed down the tradition.” For him, that tradition was embodied in a mesmerizing litany of history and tribute, this “far from complete list, in no particular order.” And so be began:

“I wish to thank Julie Harris, who explained and embodied her practice of making an entrance onstage as if she were riding an elephant while holding open an enormous green umbrella. I thank Katharine Hepburn for her generosity onstage and off, and George Rose, who schooled me in the art of charming arrogance. Thanks to Misha Baryshnikov, who manifests the genuine humility of a great artist. Thanks for the versatility of Fritz Weaver, the elegance of Nina Foch, and the extravagance of Norman Lloyd.

“Thanks to Ned Beatty, Joan van Ark, and Anthony Zerbe for the gratification of teamwork. For gifted collaborators, Richard Dysart, Peter Donat, Michael Learned, and Cicely Tyson. I thank Stacy Keach, Philip Bosco, and Lee J. Cobb for the affirmation of being privy to Lee’s dream to ascend that Shakespearean Everest. And thanks to Anne Bancroft and my lifelong and lion-hearted friend, Frank Langella, who taught me what onstage chemistry really means.

“To Blythe Danner, who personifies the theatre turning to joy; thanks for the vibrancy of Rosemary Harris, Stephen Elliott, Richard Dreyfuss, Ellen Burstyn. And for the mastery of Keene Curtis and the flamboyance of Jeffrey Tambor, the truthful clowning of Chris Murney and Bob Dishy, the humanity of Eli Wallach and David Dukes, James Earl Jones and his sexy nobility, and Raul Julia with his noble sexiness. Chris Plummer, who never settles for half, and Barney Hughes, Franny Sternhagen, and Marsha Mason for demonstrating authentic sparkle.

“For the sheer Bacchanalian lustiness of John Goodman, the exuberance of Dan Jenkins, and the caring partnership of Bob Gunton. To Michael Crawford, for proving that a basically decent person playing a singing vampire could act like a monster. And thank you to Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy, models for married artists working together with love and respect. Thank you for the suave gallantry of James Naughton and for Gregg Edelman and Randy Graff, who displayed their mojo in full-throated song.

“For all the gifted and committed ensembles full of sound and fury. I believe in ghosts. I believe in the lingering spirit of artists. So I stand here to say thank you to all my peers and fellow artists and ghosts. Thank you.”

And thank you, René.

Christopher Rawson is senior theatre critic of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and a member of the executive committee of the Theater Hall of Fame.