In 1994, New York City was drowning in a wave of gentrification that swept along neighborhoods and theatres in its path. Times Square had been sold to Disney, essentially, and Sixth Avenue to big-box stores. Small theatres were trying to get bigger, and some Off-Broadway companies aspired to produce Broadway hits. Income inequality became a fact of New York life, and at City Hall Rudolph W. Giuliani was equating freedom with authority.

Against what Cornel West called “the unholy ship of fools obsessed with money, image, status, and power,” Melanie Joseph, a Canadian who had abandoned a medical education, launched a broadside on behalf of the revolutionary traditions of art and theatre. She was determined to reconnect politics and art in ways that surpassed antecedents like the Group, the WPA, and the Living Theatre. With a radical soul, Joseph intended the Foundry Theatre to locate itself at the intersection of theatre and community organizing.

“Sometimes,” as West put it, “you must just step out on nothing and land on something.” That was the anomalous trajectory of the Foundry. There was no permanent physical space. No acting company. No consistent stable of artists. And for most of its tenure—to the chagrin of funders—no managing director. But for 24 years it would hold fast to a clear purpose and a provocative vision. In the words of one of its producers, the Foundry posited “a heroic society, daring to create its own future.” If you worked for the company, you were a social justice practitioner as well as an artist.

Rather than starting with a core group, Joseph gathered collaborators by invitation—a word that would become “a consecrated and constellating force…a proposal of kinship, a promise, and a commitment to something future.” With such an unusual and welcoming strategy, it was no wonder the Foundry attracted bright and dedicated theatremakers.

In some seasons only a single play was produced, but most were memorable and well received by audiences and the press (including 14 Obies). The Foundry premiered Tarell Alvin McCraney’s first play—The Brothers Size—and produced Marcus Gardley, Carl Hancock Rux, and the mystery man of American playwriting, W. David Hancock. Occasionally it re-envisioned a classic, such as The Good Person of Szechwan, with Taylor Mac as Shen Te. When it took on Pins and Needles—the 1937 Harold Rome musical revue, first performed by a cast of union cutters, basters, and sewing machine operators—the Foundry pushed the boundaries of art and social justice by collaborating with members of Families United for Racial and Economic Equality.

But their bread and butter was new work that challenged the idea of what a play is and what a performance event could be. One of the most memorable was The Provenance of Beauty, a narrated bus trip through the South Bronx featuring poetry by Claudia Rankine.

Theatrical production was only one facet of the company’s work; the other, equally important, was community dialogue. Utterly unlike what most theatres call “special events,” the Foundry’s outreach was consistent, penetrating, and deeply political. There were forums and teach-ins on Bosnia, food, and health care. It’s hard to imagine another theatre company reacting to Pol Pot’s killing fields with a town meeting on war crimes and genocide.

The organization’s most celebrated event, a weekend “performance of ideas” in the spring of 1998 called A Conversation on Hope, drew 300 artists and thinkers to discuss the state of the arts and the world. The mandate was to challenge artists to see their work more broadly, and it was, by all accounts, a signal happening. The company’s patron saint, Cornel West, welcomed attendees by recognizing the “sheer audacity of talking about hope in 1998, in the middle of the last empire in this dark and ghastly century.”

This storied run all came to end in early November. Despite a celebrated and debt-free existence, the Foundry Theatre shut down operations, but not without a final salvo: A Moment on the Clock of the World, which takes its title from a coinage of activist/philosopher Grace Lee Boggs, is a new chronicle by Joseph and collaborators of the company’s artistry, principles, and practice.

This storied run all came to end in early November. Despite a celebrated and debt-free existence, the Foundry Theatre shut down operations, but not without a final salvo: A Moment on the Clock of the World, which takes its title from a coinage of activist/philosopher Grace Lee Boggs, is a new chronicle by Joseph and collaborators of the company’s artistry, principles, and practice.

If ever a book embodied a theatre company, A Moment on the Clock of the World does. It is as honest, zealous, and challenging as the Foundry’s previous work. After a rousing tribute by West, critic and scholar Alisa Solomon offers an impassioned personal history of the theatre and an elegant analysis of its approach and success. “Foundry shows didn’t represent the world,” she writes. “Each show invented one.” We-were-there interviews reflect and balance the think pieces. But the book’s glue and soul is the running commentary in small print by Joseph at the bottom—the humble portion—of each page. Extraordinarily candid and introspective, it continually elucidates the content above it.

Ultimately the Foundry is likely to be an inspiration at least as much for its praxis as its productions. New work was generated by commissioning a playwright, developing the play—sometimes for years—and guaranteeing a production. Even in the Kafkaesque New York arts environment, the Foundry was a values-based theatre, and transparency was the administrative watchword. Budgets were published in the programs. And “respectable compensation became a nonstop site of inquiry.”

Collaboration was the rubric within the company as well as with the communities it built around their productions. A true believer with a restless intellect, Joseph drew inspiration from the World Social Forum, taking company members to a conference in Nairobi in 2007. It was the 2005 forum gathering in Brazil that had given her the notion of “horizontalizing” the Foundry’s leadership. The staff was reorganized into rotating groups of producers with hands in every pot: All shared the commissioning, dramaturgy, and producing. All made budgets, wrote grant proposals, audited the books, and took out the garbage. Joseph wanted everyone involved in every decision, analyzing even the most mundane subjects. The story of the day they spent debating how to organize the file cabinet is a howler. Joseph confesses “there were times we wanted to kill each other and sometimes nearly did.”

Despite having a formal proposal from producers to extend the life of the Foundry beyond Joseph’s tenure, the board of directors voted to scale down and cease operation. Unsurprisingly, scholar Diane Ragsdale contributes the book’s most piquant essay, ruminating on the company’s closing. “While some may mourn this development,” she writes, “I celebrate it… A longer life should not be conflated with a more significant one.” Ragsdale’s clear-eyed defense of the closing also raises a red flag about how institutionalization can edge out art’s most vital elements—i.e., “the artists and, with them, imagination and relevance.”

Three years before the Foundry started firing, Moisés Kaufman launched an enterprise with similar priorities. Born in Caracas, Venezuela, where he witnessed touring productions by Brook, Bausch, Grotowski, and Kantor, Kaufman was drawn to both formal experimentation and political content. After more than a decade of under-the-radar work, he emerged as the leader of a troupe he had formed with like-minded New York theatre artists, Tectonic Theater Project, which came into its own with the masterly Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde, and burnished its reputation for examining gay themes with a reportorial method in the powerful The Laramie Project and The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later.

Three years before the Foundry started firing, Moisés Kaufman launched an enterprise with similar priorities. Born in Caracas, Venezuela, where he witnessed touring productions by Brook, Bausch, Grotowski, and Kantor, Kaufman was drawn to both formal experimentation and political content. After more than a decade of under-the-radar work, he emerged as the leader of a troupe he had formed with like-minded New York theatre artists, Tectonic Theater Project, which came into its own with the masterly Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde, and burnished its reputation for examining gay themes with a reportorial method in the powerful The Laramie Project and The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later.

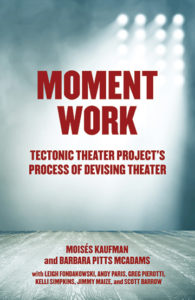

Tectonic’s devising process reflects the studies of its core members at New York University’s Experimental Theatre Wing, where choreographer Mary Overlie was teaching her Six Viewpoints—a way of deconstructing stagecraft and rebalancing it in relation to text. What Tectonic calls Moment Work, as documented in a new book of the same name, is a series of exercises designed to suspend interpretive analysis to focus on structure. Props and costume pieces are introduced and explored for their own value rather than as tools for representation.

Moment Work’s resemblance to Viewpoints is so striking that it may seem to some to be a subset, even a copy of Overlie’s work. In production, however, Kaufman developed a unique style incorporating fact-based texts, spare stagecraft, presentational breakouts, and Brechtian quotations.

Written by Kaufman, Barbara Pitts McAdams, and members of the company, Moment Work is largely a practical handbook, heavily weighted toward the exercises Tectonic uses to make its shows. These are delineated clearly, though readers with a prior knowledge of Viewpoints may find the exercises pitched toward the less initiated among the high school and undergraduate students that the company teaches.

The final third features astute essays by company members and insightful annals delineating the development of Tectonic’s major shows. Particularly intriguing is the extent to which the projects have been based on and inspired by texts, specifically books Kaufman happens to be reading. The section on Gross Indecency details how multiple sources were stitched together to produce the play’s satisfyingly ambiguous point of view.

Anyone interested in building plays based on extensive interviews will have a superb resource in the story of how Tectonic members descended on Laramie, Wyo., to research the many figures surrounding the murder of Matthew Shepard. Not knowing exactly what their approach would be enabled the valuable Buddhist perspective known as “beginner’s mind.” They realized that “more seasoned interviewers would have perhaps spent less time with each interviewee and asked more pointed questions, looking for a quote or a sound bite.” Instead, they wanted to “hear it all” and capture the experience of each interview. The result, ultimately, was two powerful pieces of theatre.

Occasionally the Moment Work concept seems stretched to cover basic practices. Kaufman cites the challenge, in his production of the Williams screenplay One Arm, of representing a character’s absent limb. After various options were tried in early stagings, he arrived at the elegant solution of having the actor keep his arm by his side for the entire performance. The process by which he reached that decision could be found in many rehearsal processes. Ironically, in this section, Moment Work takes a backseat to the canny textual dramaturgy, development, and writing that has characterized all of Tectonic’s major productions.

However they do it, Tectonic has made itself an indispensable part of the national theatre landscape. With a number of projects in development, it is likely to be a longstanding company through Kaufman’s career—and perhaps beyond.

Director and writer Michael Bloom is the author of adaptations of Nathan the Wise and Jane Austen’s Emma, as well as the book Thinking Like a Director.