Playwright Mustapha Matura, a Trinidadian native who lived and worked mostly in London, died Oct. 29.

It was a happy circumstance for Mustapha Matura that the workshop for his first commissioned play at Arena Stage, A Small World, was staged in the Old Vat Room in Arena’s basement. Given its roots in a former brewery, the venue had a fairly endless supply of bottles of Yuengling available during performances, notes sessions, and audience talkbacks.

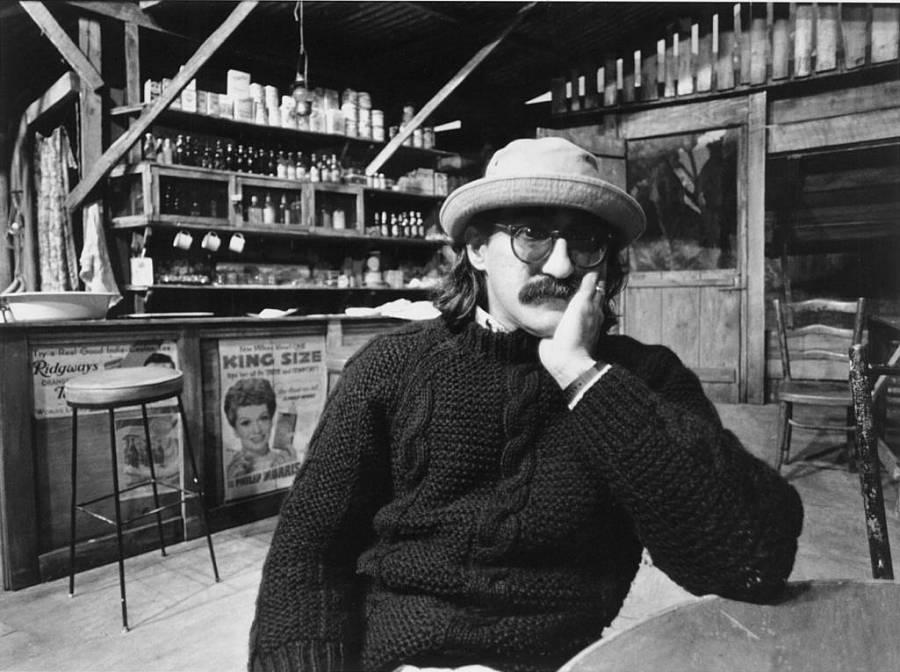

Mustapha was always happy in a theatre, but the comity of the enterprise increased exponentially if there was a bottle of lager handy—playwriting is a serious business, he would aver, but let’s not take it too seriously, man. I first met Mustapha during a preview performance of his 1984 play, Playboy of the West Indies, which Tazewell Thompson staged at Arena in 1989, following the play’s successful journey from London to Chicago’s Court Theatre. Mustapha was an unmistakable figure: lean and slinky, he sported a bushy moustache, oversized glasses, and a symphony of wavy black hair (usually shoved inside a floppy tennis hat). He rather resembled a calypso Groucho Marx, as rendered for a Saturday morning Hanna-Barbera cartoon.

His voice was even more idiosyncratic: a mellifluous wave of elongated and careening syllables, enthusiastic and skeptical at the same time. He enjoyed the success of Playboy, but he didn’t stay long in his visit from his London home base, nor did he fret too much about the production; that wasn’t his style. Playboy was a vastly enjoyable and playful construct—a resetting of J. M. Synge’s Playboy of the Western World from 1912 Ireland to 1950 Trinidad—but it was much more than that. Mustapha was struck by an odd coincidence that the self-absorbed setting of the Synge play, Mayo, was only two letters shorter than the self-absorbed fishing village on Trinidad’s southern coast: Mayaro. Mustapha’s transposition resurrected the original play’s political edge for the late 20th century. As a colonized nation, Trinidad had become too enthralled by the smoke and mirrors of myth and imperialism, in his view; it needed to fall in love with its own culture, its own people, its own identity. This would be an ongoing theme in Mustapha’s work.

He expressed this conflict most movingly in his next project with us at Arena, Trinidad Sisters, which we had the privilege of presenting in its American premiere in 1990. It was, in my opinion, one of the most successful cultural transpositions in recent years, moving Chekhov’s story to Trinidad during the Second World War, when a British Army unit tries to raise a local Trinidadian regiment to help defend the island waters against Nazi U-boats. A privileged family of Trinidadian sisters (raised in Cambridge, England) are hopelessly enraptured by the British soldiers at the emotional expense of their own countrymen. Mustapha’s play is judgmental in a way that Chekhov’s isn’t (“Moscow, Moscow! They’re not sufferin’—they’re fine!,” he told me), and the poignant cultural divide between the British colonizers (who are not very compelling) and the local islanders (who are) makes for a fascinatingly political play. It should be seen again.

Based on our relationship with Mustapha, we commissioned a world-premiere play, A Small World, directed by Kyle Donnelly, a two-hander set in a Jamaican bar in New York City. Mustapha preferred to stay in London for most of the developmental work; he had his own relationship with the Tricycle Theater there and was more comfortable creating work in Kilburn, the multicultural area in which he lived. “The climate helps a lot with my writin’—it’s the grey winters, man,” he explained. Still, his visits usually brightened up the rigors of playmaking—he always sought out sociability and amusement rather than conflict and stress. He assumed the folks hired to do the work knew what they doing.

His last great magnum opus, The Coup, played at London’s Royal National Theatre in 1991; it, alas, seemed too “inside” for us to produce at Arena, and our relationship with Mustapha slowly attenuated.

Mustapha Matura was a trailblazer within the highly regulated world of British theatre: He was the first British-based playwright of color to have a play produced on the West End (Play Mas, back in 1974). But at Arena Stage in the late 1980s and early ’90s, he was a transitional figure for us and our audiences. Born of an East Indian father and a Creole mother—with Scottish and African ancestry—he was a walking catalogue of cultural diversity. As an émigré from Trinidad, he deeply understood what it meant to lose one’s original cultural identity and trade it—surrender it, really—to the larger imperial seductions of British (and American) culture. He always shook his head wistfully at the bad bargain of that exchange, but rendered his discomfort and outrage with a sense of humor and irony that would be much welcomed in today’s theatrical universe.

In Mustapha’s version of Playboy, the local barkeep, a garrulous Trinidadian much attracted to extravagant embellishment, criticizes someone’s wasted trip, expounding on his own unique theory of time and space: “Jim, is like dis: If I go down dere, or anybody go down dere, an stay shorter dan it take dem ter go dere—dey ent really dere.”

Mustapha Matura was really dere.

Laurence Maslon is an arts professor at NYU’s Graduate Acting Program. He was dramaturg and associate artistic director at Arena Stage from 1988-1995.