I’ve started this obituary a dozen times.

There’s a clever intro or anecdote I could lead with, but it eventually comes back to the same thing: He’s gone. My best friend has moved on. I know that he’s telling my mother about the time we spent together. I grin when I think of how he and his mother are catching up. I laugh out loud when I think of the collaborations, he, August, and Claude are cooking up. But it always comes back to: I must learn to negotiate a world without Marion McClinton.

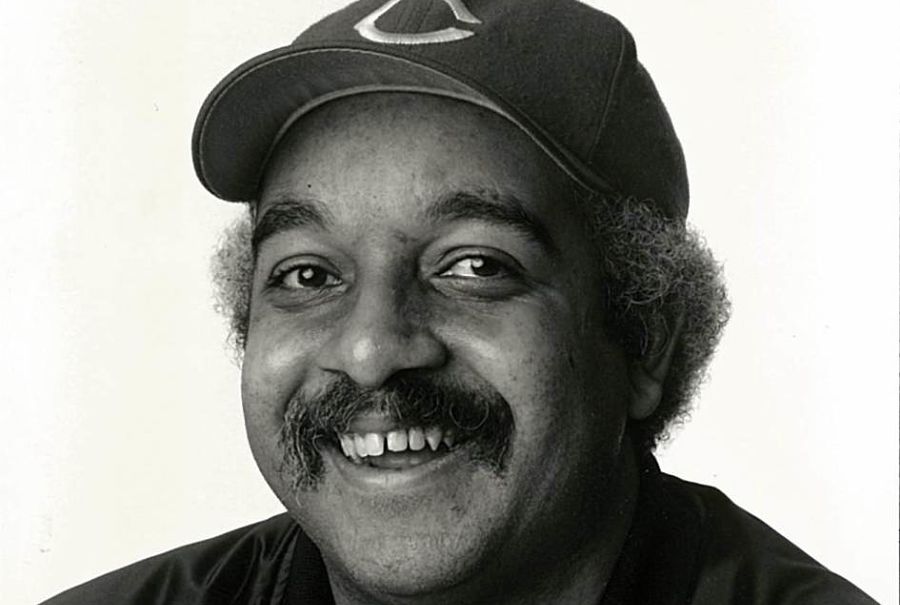

In 1976, when we met, there was no way we could know that standing outside the Firehouse Theater in Minneapolis on our first day as professional actors would be the start of a bond that would span countless sports arguments, brushes with immortality, marriages, divorces, births of children, deaths of parents and siblings, Broadway, and the fulfillment of most of our hopes and dreams. In the final weeks of his life, we were alone, and he said, “Dub, man—I’m realizing I’m never going to direct again.” After a long pause he added, “What am I going to do? That’s all I am.” “No, that’s what the world knows about you,” I replied. “That’s what newspapers will say but you’re so much more.”

And he is. Most people will never know that he got equal enjoyment spending hours with fledgling actors at St. Paul Central High School discovering their voices as he did working with Broadway stars. Moreover, he talked to them both in the exact same way, with stories from his past that planted seeds of encouragement and confidence and brought them back from the fear of failure that lives in all actors. His commitment to inspiring every writer who crossed paths with him was legendary. He opened doors, bringing young directors in regional, Off-Broadway, and Broadway rehearsal spaces, only requiring they do the same for those that followed them. Most of the theatrical world is unaware he turned down the artistic directorship of a major regional theatre rather than uproot his son, who was about to enter high school. Family came first.

He was a true son of St. Paul—just ask any interviewer who said he was from the Minneapolis or “the Twin Cities.” He got his start as a playwright at the Multicultural Resource Center on St. Anthony and Victoria writing history plays after hours, based on the lives early Black Minnesotans. He was instrumental in developing the jazz acting esthetic at Penumbra Theatre, always carrying a yellow legal pad with pages of script titles to suggest and casting ideas.

I don’t know much about his life on the road. We made it a point to never talk about that, because we both felt it was important to for him to have a relationship with someone who didn’t want anything. He was indefatigable. When health issues made the life on the road unbearable, he came back looking for new challenges and finding a new home at Pillsbury House Theater, championing another generation of writers whose work he consumed when the pain wouldn’t let him sleep. He created pathways for the next generation of African American actors in Minnesota and did some of his best work. He made himself accessible to everyone I brought to the house.

My primary memory of him there is sharing. He had a story for everything, and he was never the center. Either his mother said, or August used to say, or the time George C. Wolfe remarked…then he would drop the knowledge. Like he was just the repository of the wisdom, not the one that always brought up the right story at the right time.

It’s impossible to talk about Marion without talking about him “in the room.” Rehearsal room, that is. That’s where he came to life. In the room his kidneys didn’t hurt. In the room he was following his calling. In the room he was still close to “Mr. Wilson.” The good times were just a story away. It was always difficult for him to leave the room. Whether it was at the end of the rehearsal day or giving the state of the union (his term for the final time he addressed a cast before opening), leaving the room meant returning to real life. To a failing body and an art form filled with people he sometimes thought had forgotten about him.

In the room he was the most patient director I’ve ever worked with. In the 45 years we worked together he never said, “We don’t have enough time,” or “We need more time.” The time we had was the time we needed. I’ll say now: Marion, we need more time. Let’s talk about that the next time we get together. Rest in power, my brother. And so it goes.

James Williams, a mainstay of the Twin Cities theatre scene since 1976, was a founding member of Penumbra Theatre.