By the time you read this, patriarchy will be a thing of the past. In separate interviews, celebrated co-artistic directors Shermin Langhoff and Jens Hillje insisted matter-of-factly that Rewitching Europe, a new production premiering at Berlin’s Maxim Gorki Theater this fall, is what will do the trick.

“It might take some time to figure out what comes next,” Hillje conceded, seated at a picnic table in the theatre’s courtyard café late this summer. “Shifting from a culture of domination to a culture of cooperation is quite a challenge,” he said. “But it starts on the first of November,” referring to the date of the play’s premiere.

Langhoff and Hillje were only half joking. Such disarming humor and bold assurance is characteristic of the Gorki’s vibrant and radically engaged artistic works. The smallest of Berlin’s five state theatres, the Gorki is also the youngest and most diverse, both in the makeup of its artistic ensemble and the audience it attracts. Since 2012, when the city appointed Langhoff artistic director and she named Hillje her partner, the Gorki has twice been deemed theatre of the year by leading arts publication Theater Heute, and the pair has received the Berlin Theater Prize for “representing the city’s population in its diversity.”

Both spoke eloquently and passionately about the Gorki’s commitment to sharing the untold stories of marginalized groups, shining light on blind spots that, once illuminated, force audiences to see the world and the people around them in new ways. “If you ask me in one sentence what Gorki is about,” Langhoff said in her office one September morning, “I would say it is taking history personally.” Added Hillje, “The major project of the Gorki as a whole is always to create common ground. Common ground won’t work if it’s not based on understanding.”

At the start of her tenure, Langhoff overhauled the resident ensemble to include a majority of actors with origins outside Germany. The move reflects an overall effort to focus on narratives long absent from Berlin stages—not simply as a matter of principal, but because Langhoff and Hillje take seriously the Gorki’s position as a state theatre, beholden to the citizens of Berlin. That means developing stories that speak directly to the city’s history as a nexus of conflicting cultures and a center of immigration. “Everybody has the right to have a theatre that represents him or herself up onstage and reflects [their] stories,” Hillje says. The Gorki has become a kind of model in this regard; over the past several years, they’ve seen other theatres follow suit in diversifying their companies.

The theatre made waves in 2016 with the founding of its Exile Ensemble, comprising seven professional actors from Syria, Palestine, and Afghanistan who had been forced to live in exile. It was part of a cultural response to the swell of migrants arriving in Germany from the Middle East in recent years. For its first piece in 2017, the ensemble worked with Israeli-born resident director Yael Ronen to create Winterreise, devised during a road trip the artists took together through Germany, reflecting on how they were perceived by their new countrymen and by each other. In the few years since, the Exile Ensemble has largely been folded into the main company, which shares the objective of investigating identity and belonging through collaboration.

With 25 actors on fixed contracts, three to four resident directors, and as many full-time dramaturgs, Hillje estimates the Gorki family to include 60 to 80 artists. In addition to the theatre’s mainstage, an adjacent building branded Studio serves as a secondary stage where “radical new forms and political theory merge.” This year Gorki constructed a temporary structure on its front lawn dubbed “The Container,” to house productions while each of the two permanent spaces underwent necessary technical upgrades. The theatre will continue to present additional programming in the Container at least through the 2019-20 season.

The Gorki doesn’t commission plays and only occasionally revives classics, which Hillje considers rarely capable of reflecting today’s everyday realities. (This fall the theatre premiered Anna Karenina or Poor People, a mashup of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky adapted and directed by Oliver Frlji as an intersectional investigation of class and gender.) Hillje estimates that 90 percent of Gorki productions are devised projects, in which writing is part of a collaborative creative process that can take months or years, depending on the piece. Many such works cannot be produced elsewhere or without their founding actors, whose personal histories are woven into both the stories and their presentation. “Always for me the question is why,” Langhoff said of recruiting artists to work at the Gorki. “Why are you an artist? Why are you doing theatre? Why are you telling stories?” Being part of the Gorki ensemble means having something to say and a strong desire to transform those who hear it.

Ronen is particularly celebrated for this collective approach to storytelling; her projects with the company most often credit both herself and the ensemble as authors of the text. She’s the director Langhoff and Hillje trust to usher in the era of post-patriarchy with Rewitching Europe, an examination of witch hunts in Germany which illuminates the ways that persecution “is written into the bodies of women, and how these bodies can free themselves from an experience of oppression.” Roma Armee, another of Ronen’s popular pieces still in repertoire, presents a collective reclaiming and musical celebration of Roma identity featuring guest artists of Roma descent from across Europe bearing their true stories.

Langhoff’s appointment to lead the Gorki was itself a landmark moment: She became the first female artistic director of a Berlin state theatre in more than 30 years, and the first of Turkish descent. Having led an independent theatre in Berlin-Kreuzberg, where she coined the term “post-migrant” theatre, Langhoff represented a clear move toward embracing a greater array of perspectives. Hillje, recently honored with the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale for his lifetime of work in the field, brings a deep well of experience in Berlin theatre, including as chief dramaturg at the Schaubühne, another state theatre he helped shape alongside Thomas Ostermeier and Sasha Waltz.

Both Langhoff and Hillje consider how the history of the company and its architectural home necessarily inform the Gorki’s role in city life. Situated in Berlin’s central district of Mitte, formerly East Berlin, alongside more physically imposing cultural institutions—Museum Island to the east, Berlin State Opera and Humboldt University to the south, and Berlin Cathedral to the west—the venue was conceived along more populist lines. Completed in 1827, the building was first a gathering place for the Berliner Singakademie, a choral society, and the city’s first public concert hall. In 1848, it was used by the Prussian National Assembly to draft a constitution for a Prussian Republic that never came to pass, cementing its history as a seat of democratic ideals. The building suffered damage during World War II, and in 1952 became home to the theatre, which took its name from Soviet writer Maxim Gorky, a pioneer of socialist realism. At the outset it produced German translations of Russian Soviet works, but by the late ’50s, during something of a cultural thaw, it began producing more critical, dissident works by the likes of Alfred Matusches and Heiner Müller.

Though the German Democratic Republic is a thing of the past, the Gorki is still funded by the state it has often critiqued. Together Berlin’s state theatres receive around half of the city’s 600 million euros in annual cultural funding; more than 85 percent of the Gorki’s 15-million-euro operating budget comes directly from the city. (By comparison, New York City’s Department of Cultural Affairs dispenses less than half as much in total each year.) Robust government support is an essential part of the German artistic tradition, as is the expectation that such institutions scrutinize the state and its citizens. This also means the ability to welcome a wider array of patrons through the door than tends to be the case in the U.S., where the cost of admission can limit access. With ticket prices averaging around 20 euros (every ticket for the Container is 16 euros), and regular discounts for students, the unemployed, and others facing barriers to access, the Gorki is among the most affordable of Berlin’s state theatres. Providing English surtitles for every production is another move to open the thea-tre’s doors to as many as possible.

In both projects devised with the actors who perform them and less overtly collaborative pieces, the Gorki adheres to the Brechtian principle that a performer’s identity is never separate from the performance. “The citizen is always present,” Hillje says, “as a social, cultural, political being.” Even in this season’s playful opening piece, directed by Sebastian Nübling, Herzstück (or Heart), based on a 14-line dialogue by Müller, the actors are dressed as clowns performing physical and mental acrobatics, but glimpses of their true identities ground the antics in contemporary politics.

Cultivating a richly diverse ensemble means containing opposite sides of identity-based conflicts—say, between Israeli and Palestinian, or Sunni and Shia—within the company. “This enables us in a unique way to criticize everyone,” Hillje says. Though freedom of expression in the arts is a constitutional right in Germany, as in the U.S., the Gorki does receive blowback from the country’s far right, whose rise in turn fuels the urgency of the theatre’s work, both onstage and in its extensive non-theatrical programming.

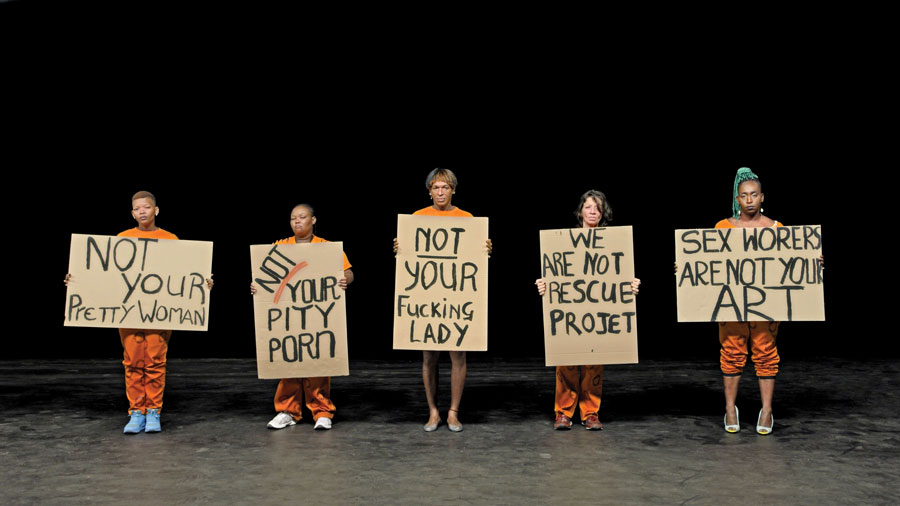

In late October, the Gorki hosted its fourth Herbstsalon (or Autumn Salon), an interdisciplinary conference encompassing visual arts, installation, theatre, lectures, and discussions in conjunction with Humboldt University. The salon has been held every two years since Langhoff began her tenure in 2013; this year’s mission and title was “De-Heimatize It!,” and it was billed as a discursive intervention in response to the founding of a heimat or “homeland” ministry in Berlin. (In German, the word heimat has even stronger conservative nationalistic connotations than “homeland” does in the U.S., so the ministry’s founding signals a worrying trend.) In addition to hosting exhibitions and lectures, and inviting an international group of young activists to address “constructions of nation and belonging from an intersectional feminist perspective,” the salon also featured five stage premieres with a similar aim.

Langhoff estimates that 40 percent of the Gorki’s work occurs offstage, in site-specific works as well as in classrooms and workshops with young artists. Last year, the theatre staged a piece called Grundgesetz, named for the Federal Republic of Germany’s Basic Law, in front of Brandenburg Gate, a towering city monument just a few hundred meters from the theatre. To mark the law’s 70th anniversary, Polish director Marta Górnicka adapted its text into a libretto performed by a diverse company of 50. The project was billed as a “choral stress test” of the resilience and inclusiveness of the law in a time of far greater heterogeneity than when it was conceived. Another piece in development will be devised by an ensemble of refugees who came to Germany as unaccompanied minors, reflecting on their treatment by society and search for a sense of belonging.

“I don’t think theatre can replace politics,” Langhoff said. But she believes it can be what she calls a “fortress for democracy.” She went on, “There is a next generation that we are responsible for,” and posited that the full lasting impact of the Gorki’s work may not be immediately apparent but ripple out over time. Given the many challenges to a free and just society emerging across the globe, the Gorki’s position as a safe space for the marginalized is as urgent as ever. Beyond the stage, Langhoff imagines the Gorki as an academy of politics and aesthetics, exploring new forms and systems of thought through art. “So as long as we are needed, we will do it here.”

Naveen Kumar is a writer based in New York City.