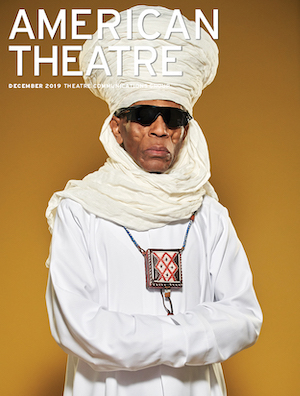

There is perhaps no better word for André De Shields than the one his Hadestown costar Eva Noblezada invokes when asked the question: royalty. For more than five decades, this Baltimore native has left his mark onstage as an actor, dancer, singer, teacher, choreographer, and director. As such he’s something akin to the king of the American theatre. The Wiz, if you’re nasty.

With a presence both impish and regal, De Shields gave life to the titular illusionist in that seminal yellow-brick-road musical by Charlie Smalls and William F. Brown; set the stage on figurative fire in the classic revue Ain’t Misbehavin’; and since March, and for the foreseeable future, he stars as an unspeakably dapper Hermes in the Tony-winning Hadestown. In June he took home his own Tony Award for the musical, but not before delivering an instantly iconic speech in which he gave his three rules for “longevity.”

“One: Surround yourself with people whose eyes light up when they see you coming,” he said, dressed in a stylish, black silver-embossed jacket and Hermes-inspired winged gold sneakers (the same ones he wore for this American Theatre photo shoot). “Two: Slowly is the fastest way to get to where you want to be. Three: The top of one mountain is the bottom of the next, so keep climbing.”

To watch André De Shields perform is to see “a five-act play contained in the descent of two steps,” as Rachel Chavkin, who directed him in Hadestown, puts it. When he arrives for this interview, wearing a dark blue tracksuit with bright orange stripes, his salt-and-pepper hair shining like a crown, he is unassuming yet calculating. He measures out the room with one glance, slinks into his chair effortlessly, and assumes the position of someone poised to enlighten you on all the secrets of the universe. The whole world seems clumsier in his presence.

He instantly says your name, and will return to it at moments in the conversation where comfort or special attention are needed. It reminds me of something Yvette Gonzalez-Nacer told me; she plays one of the Fates in Hadestown, and she recalled the night De Shields “extended his handkerchief to an audience member who was visibly devastated by the tragic ending.”

When he pulls his handkerchief from his small bag during our conversation, he extends it, then picks it up, in a precise impression of someone he knows who was among the inspirations for his silky performance as the Greek god. But as the handkerchief lies horizontal on the table, suddenly it is the marble Acropolis where he shares his wisdom, the stars he uses to explain why astrology isn’t all nonsense, and a portable stage where he’s always willing to perform. When he puts it away, the illusion seems to disappear with it. And as he vanishes into the crowded streets of Manhattan as if into a cloud, he leaves behind a trail of pure awe.

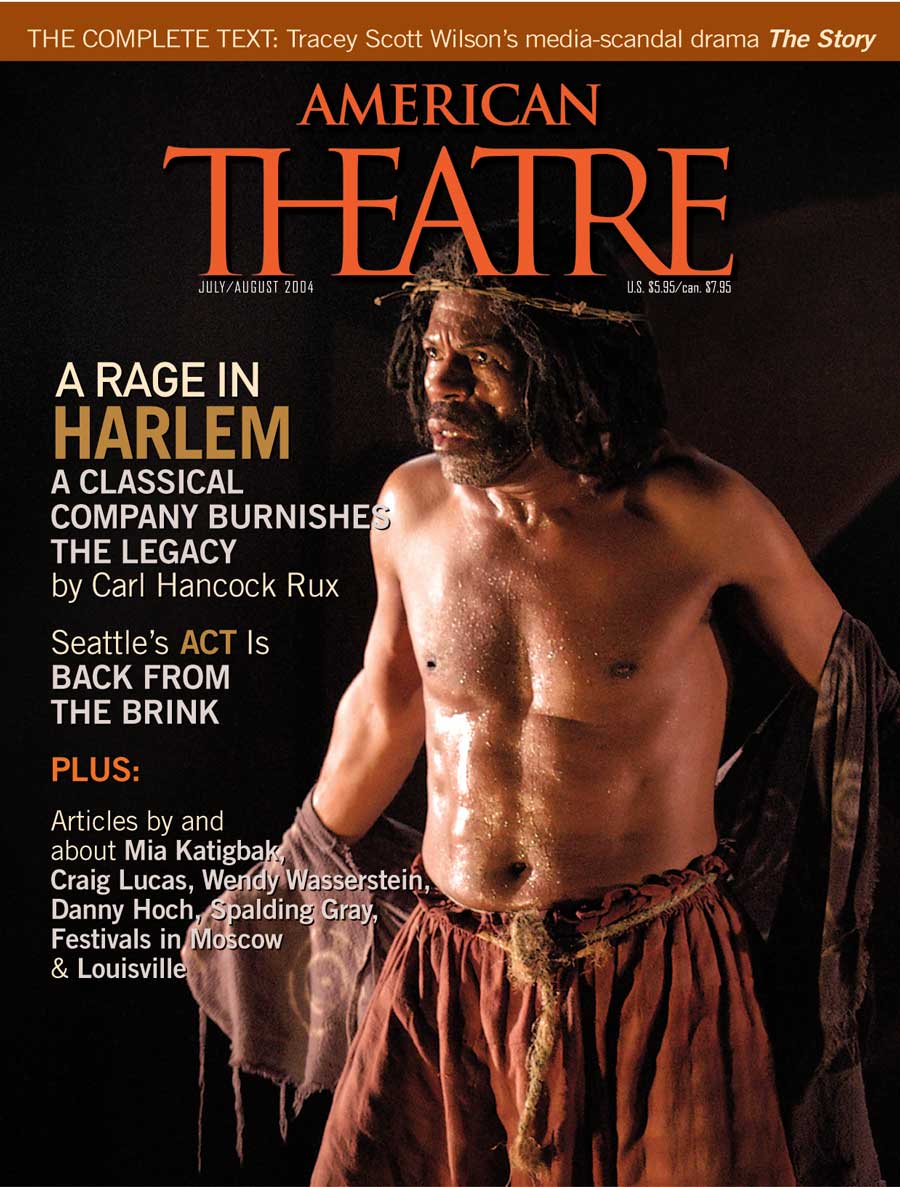

JOSE SOLÍS: You were on the cover of American Theatre in 2004. What was that time in your career like?

ANDRÉ DE SHIELDS: This is a production shot from Derek Walcott’s Dream on Monkey Mountain. Derek Walcott—he’s a brilliant mind and a great playwright who worked in Trinidad and Tobago and who is no longer with us. The play has been described as the Trinidadian King Lear. The Classical Theatre of Harlem, which is now served by Ty Jones, was founded by Alfred Preisser in 1999, and he directed this play in 2003. I give you all those specifics because in my career, which now spans 50 years, it wasn’t until then that I was perceived as, cast as, and reviewed as, a leading man.

I did five consecutive productions with them in which I was cast as a central character and leading man. So not only am I paying homage to Alfred Preisser but to Derek Walcott, who did not receive the kind of respect that Shakespeare gets for his canon, and which he deserved. And it got my first cover on American Theatre magazine. When you look at it, it’s not the man you’re interviewing right now: facial hair, dreadlocks, a robust body, a six-pack. [Laughs].

Everybody who saw this cover told me to ask you about the six-pack.

That’s a memoir: André De Shields, How I Got My Six-Pack. Shortly before this, I had finished my run in the Broadway production of The Full Monty during which we, the six leading guys, actually did perform a full monty. So we wanted the best bodies we could have, while at the same time looking like blue-collar workers. We weren’t stud muffins, but we were robust.

I’ve heard many actors who say every time they work on a different project they start as if they’re resetting everything about themselves. You seem to approach your work as someone who can’t deny their legacy.

No, and I don’t attempt it. I’ve been so blessed that I have been a creator, as opposed to someone who’s replacing, or someone who’s following another person in a role. I’ve been able to create roles. I’m also careful too. When I’m blazing a trail or when I’m opening a door, on the trail I leave bread crumbs for those people who are following in my wake. The doors that I opened, I leave them open for those individuals who are inspired by the work that I’ve done.

Part of the satisfaction of being a creator of works is that there’s an entire community and generation of individuals after me who have stood on my shoulders. So it’s nice to create employment for other people, including Richard Pryor, who played the Wiz in the film, and Queen Latifah, who played the Wiz on the television version. I’m happy to create work for other celebrities.

Was there a specific moment when you realized you were a trailblazer?

It’s a moment that I continue to realize. Let’s talk about Hermes in Hadestown, for instance: Every day since the Tonys, there is someone who wanted to stop me and thank me for finally getting the props that I deserve, which means to me that there has been a community of people who have been personally invested in my journey and now have an opportunity to express it. Whereas if they had said it previous to this point, it would have been premature. It maybe might’ve spooked the gods and it wouldn’t have been delivered now. I never want to have to say, “I’m sorry, I don’t have time.” I want to be able to stop, have this exchange, receive that extra blessing, and go on my way.

I believe if you know something, share something. So I knew I had this rarefied platform at the Tony Awards to distill everything I have learned in 50 years and drop this wisdom bomb so it would hopefully serve the many people who are watching. Little did I know that it would go viral. Two days after the Tonys I encountered a group of young people on my way to the theatre, and one of them points at me and says, “There’s Hermes,” and the whole group goes “icon,” they’re genuflecting and going “icon, icon,” and I look over my shoulder thinking Denzel Washington is on the street. And then I see the leader of the pack as it were. He’s wearing a T-shirt with my acceptance speech printed on it.

Two days after the Tonys!

My mouth dried up and I was, as the British say, gobsmacked. So I stopped and asked, “Have you ever seen a Black man blush?” And they all sort of giggled. I said, “Well, here it is.” And that’s when I realized that I needed to change my public behavior.

Change it how?

Into epic patience. Because that group of young people would be followed by any number of people who would want to have me stop and receive the blessing that they wanted to anoint me with.

Everyone mentions all the hats you wear. Would you say that your educator hat helped you distill this wisdom that you’re talking about?

You’ve expressed it exactly correctly. When I do my master classes I share this with my young participants. What I’ve learned is that there are only two guarantees in this industry. And of course when I say that the eyes widen—and I quickly say, it’s not fame and fortune, it’s rejection and insecurity. You’re going to experience rejection every day. That’s the name of the game. For someone every day, you are not the winner, you are not the package, you are not the choice. “We’re going in another direction.” That’s the definition of rejection.

It even rhymes!

Oh, yay! That’s serendipitous rhyme. Part two, every day you’re going to experience insecurity. That’s the flip side of being rejected. You start questioning yourself, why am I not good enough? How can I change myself to be the package that is chosen? Now here’s the hard part. When you get hungry, and you will definitely get hungry in this industry, and I’m meaning metaphorically and literally, if you can make your meal of rejection, when you get lonely if you can make a companion of insecurity—that is the universe conspiring with you to say this can be your chosen profession. If you choose it, it will choose you in return. Next is an even harder test.

What is it?

Well, you’ll know when it stops. I follow my own advice, and one of the three things I said in my Tony speech is that at the top of a mountain is the bottom of the next. So when you pass arithmetic, you have a moment to celebrate. But what’s waiting for you? Mathematics. You pass mathematics, celebrate. What’s waiting for you? Algebra. You pass that, etc.

You seem to know yourself so well.

[Smiles] I’m so happy to be able to share this with you, because none of my other interviews have led to this particular point: my Pythagorean approach to Hermes. People have mentioned things like precision, how I’m monstrously slow, exactitude, “you float,” and all that sort of stuff. What I’m doing is creating an equation of the universe in which we exist based on the most ancient clock of all: the sundial. If you can recall your experience at Hadestown and understand how much use the stagecraft makes of shadow, darkness, ether, which helps to illuminate the shadow side of things, then think of why Stonehenge is so important.The beauty of Stonehenge is you go early in the morning and the shadows of the rocks tell you the time of day. As the sun rises, the shadows are cast in one direction. As the sun reaches midday, there is no shadow because the sun is at its zenith. As it goes towards setting the shadows, flip to the other side. That is the original Pythagorean expression of mathematics: the position of the sun in the sky. That is what I do with Hermes. He is the sundial, and it is his position on the stage which helps the audience better understand the story that’s being told. That’s the equation of that show. I’m not saying that’s what Rachel Chavkin directed. I’m saying that’s how I approach Hermes.

When Hermes reappears, time has shifted. There are pauses in the action where the audience is given an opportunity to catch up.

If you are always a student, how has this helped you become a veteran?

The beauty of this kind of life is that one can be revered as an artist, but if one continues to be a student, one creates a curriculum vitae as impressive as the acting résumé. I say to my students: If at the end of our experience you have not become the teacher and I have not become the student, then something is askew in our approach to education. We have to change places. We have to flip the script or nothing has been learned.

Was this kind of exchange or dialogue what interested you in this art form?

Exactly that. The art of being an artist is service.

What is the service?

There are only two destinations for public worship. One is the temple or church. The other is the theatre. In the current time, we are being cautioned to avoid places of worship because that’s where death is raining down. So what’s left? The theatre. The terrorists, whatever brand you like to blame, haven’t discovered the power of the theatre yet, which is why I don’t like when journalists refer to wars as theatre or terrorists as bad actors. If you go to a temple or a church, the artist, the pastor, the reverend, or whoever the leader is, is serving the soul, the spirit. If you go to the theatre or whatever, the performative arts, the artist is serving the soul or the spirit.

Who were your gods growing up?

They were all from cinema. Take a guess!

Lena Horne?

She’s somewhere in there. But we’ll get back to her later. It was Yul Brynner. That explains where I learned my strut for The Fortress of Solitude. In all of his films you will see a scene where he walks across the screen—his swagger is never better than in The Ten Commandments, where he plays Rameses in that gold skirt and gold sandals. I watched that and said, “Yes, I want to walk like that.”

I love that you have an Emmy for your work in Ain’t Misbehavin’, a performance you did onstage originally. Theatre is so fleeting, but you have at least one of your performances captured for all of eternity. As someone interested in change, is it strange to have that one moment carved in time?

It is not strange. The appetite for that has now been sated. So now I can hunger for other things. I continue to think that the magic of live performances is that it is ephemeral. However, when we talk about legacy and my personal journey to break the Methuselah code—one of my aspirations or my goals is to break this code, and for that one needs a digital version of one’s achievements. Before that I had to carry Ain’t Misbehavin’ in my interior storage. Then what happens? You get filled up and there’s no room for other creation. But if you can take that which you are done with and put it on display, then you have created room for other creativity. And because there is an eternal replica, people who are too young to experience it have watched it. This allows me the freedom to cannibalize my own work, so that when you come to see Hermes, you are seeing a bit of the Viper from Ain’t Misbehavin’, a bit of the Wiz, and other things you would be aware of if you had only seen them.

What is the Methuselah code?

I went to a TCG conference in San Diego where I led a breakout session for the “wellderly”—elder artists who were still “kicking ass.” Methuselah reportedly lived for 969 years. I thought, how did he achieve that? He lived for 969 years because his legacy was perpetuated.

You worked with Michael Bennett and Michael Friedman, so you’ve seen emerging people who were gone too soon. What did that teach you?

And I worked with Geoffrey Holder, who was here before me, who was a legend in his own life, who mentored me and whose eulogy I wrote for American Theatre magazine. I’ve worked with people who are considered great in this industry whose legacy I won’t contribute to. When we did the revival of Ain’t Misbehavin’ one day at the end of the show at the stage door there was this group of three, and the eldest says to me, “I hope you don’t mind that I saw you as a child in The Wiz.” I say, “No, I don’t mind at all, because if I dropped dead right now, I will have made my mark.” And she says, “My mother brought me, and this is my mother, and she is bringing her grandchild to see you in the revival of Ain’t Misbehavin’.” Three generations of women who had seen André De Shields play the Viper.

As a Black man you’re living history, which is something that’s been denied to minorities and obviously to Black people, especially in the U.S. Every time you enter a room, you have history with you, and no one can take that away.

I do not self-identify as a minority. I did an interview where I was asked about representing minorities. I asked the interviewer to look at me. What you should be seeing over my shoulders is the African diaspora. And that is no minority; humanity walked out of Africa. Now I know why we use the term minority, but that’s a political construct. And that is used to oppress me. And I refuse to be oppressed. Regardless of what is intended by my would-be oppressor, I refuse to be oppressed. I am a free, liberated man by birth. So when you see me, see Africa. When you see Africa you’re looking at the world.

Can we go back to Lena Horne?

In the ’70s men could be beautiful. I’m still fighting that battle. It was highly visible then. We could wear platforms, bell bottoms. And that’s what the Wiz wore: skintight bell-bottoms, five-inch platforms, big hair, makeup, capes. So the entrance to The Wiz is 17 steep steps with dry ice happening. I’m concerned, how am I going to do that in these platforms? Geoffrey Holder said, “Don’t worry, listen to mother, I will teach you Lena Horne’s secret.” The secret turns out to be that in heels on stairs, what you do is put the back of the heel against the step, turn out, and slide the foot down, and you don’t have to look down. And that’s how I made my entrance down the stairs. Being Lena Horne.

We could make an encyclopedia of André De Shields references.

Along the same line of precision mathematics and so forth, when I was trying to put facets of personalities that I admire together to create Hermes, I went to Charles Laughton and Diana Ross.

That sounds like apples and oranges.

Well, they’re both fruits. In Witness for the Prosecution, Laughton is the epitome of precision; he doesn’t make a move that doesn’t have meaning. Diana Ross is the epitome of the glittering trinket. I borrowed from both. I put them both together. So think of the silver suit, the Cuban heels, and a move that’s not wasted. It’s Charles Laughton and Diana Ross.

If you were Auntie Mame, what would make up your banquet?

If I were Auntie Mame I would talk about authenticity. And I’m looking at the potential reader when I say this, at the person who’s going to read this article: There is no one like you. There has never been anyone like you. There will never be anyone like you. Therefore know yourself, be yourself. Authenticity is everything.