In the early 2000s, actor Conrad Ricamora was playing a Chinese character in a local community theatre production of Anything Goes. During the first week of rehearsal, the director asked him, “Can you be more Chinese?” Ricamora is half Filipino, half white.

“She wanted me to be like”—and here Ricamora slants his eyes, sticks out his front teeth, and chortles, “Oh ho ho ho.” As a college graduate without any formal theatre training, he got his introduction to acting via that Anything Goes. He says now it felt “icky, but I wanted to be able to keep doing the show and I fucking did it. And still to this day I feel terrible that I did it,” he says with chagrin, adding bitterly, “Can I be more Chinese? Well, I am Asian, so how about I just, like, be myself, and not this cartoon you want me to be?”

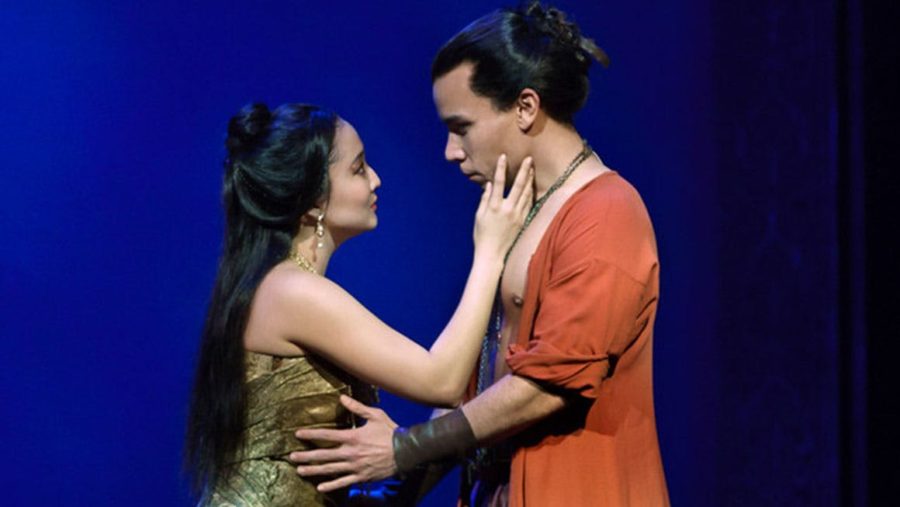

Ricamora is no longer playing a cartoon. He’s currently flying between Los Angeles and New York, simultaneously filming the sixth and final season of “How to Get Away With Murder” on ABC, where he is a series regular as Oliver, an out, HIV-positive man, and starring in Soft Power at the Public Theater (through Nov. 17). A new musical by David Henry Hwang and Jeanine Tesori, Ricomara also starred in Soft Power last year in Los Angeles and San Francisco. He plays Xuē Xíng, a Chinese entertainment producer who wants David Henry Hwang (played by Francis Jue) to write a musical about China that can play on Broadway. The country is after soft power, something America has in spades, which Xuē defines as “our ideas, inventions, culture,” which can “change the way people think.”

Xuē is a leading man in the Rodgers and Hammerstein mode: dashing and principled, and a swoon-worthy tenor. “Xuē Xíng is coming over to work with David to get representation for his people,” Ricamora says. That’s a sentiment he relates to, and something he’s able to channel in playing the character. “I feel like I want to get representation for us as Asian Americans. I feel that need strongly, and I can infuse that—my own personal will—to his will through this.”

On the day we speak, three hours before he’s supposed to go onstage, Ricamora has just flown in after shooting in Los Angeles for three days (Billy Bustamante is his alternate when he’s out of town). He’s just gotten a haircut and is trying to get his laundry picked up. It’s a hectic schedule, but to Ricamora, it’s worth it. In person, the 40-year-old actor is youthful with an aw-shucks air. During our conversation, he alternates between serious circumspection and wry quips punctuated with a goofy smile.

“When do I get to pass up a leading role?” he says rhetorically backstage at the Public. “Asian men don’t get the same opportunities to lead shows—we can be supporting. I’m very aware of the marketplace that I’m in, and so I had to make this happen.”

To say more about Soft Power is to dampen its idiosyncratic pleasures. But the next part is important (spoiler alert). Mid-way through Act One, David falls into a coma and imagines a musical where (stick with me here) Xuē Xíng has a fateful meeting with Hillary Clinton, and as they fall in love they also debate American vs. Chinese values, and the way the U.S. is viewed on the global stage. The whole thing is also a kind of send-up of The King and I, except in this case it’s the Asian man teaching the white woman a thing or two, with Asian actors playing white characters. And there’s a polka. You might call it Clinton and I.

It’s multilayered and unapologetically political. Among Soft Power’s targets is American democracy itself. After all, if it were truly representative, why is the person who got three million fewer votes president? It’s a skepticism that Ricamora has shared since 2016.

“I’ve never been a part of a show that’s been so current with themes that are affecting our lives daily,” he says, visibly concerned. “I wish it wasn’t this urgent, because I wish that we lived in a democracy that we felt secure in and it wasn’t being suppressed, and it wasn’t turning into a situation where money was ruling and not people’s voices. But here we are, and it feels like we’re in a really big fight.” He is also concerned as a gay man living under an administration bent on curbing LGBTQ rights. “It feels very real, the thought of, Am I going to be able to live here?”

Ricamora has felt like an outsider for much of his life. He was born in Santa Maria, Calif., but moved frequently, as his father, Ron Ricamora, was in the Air Force. After stints in Denver and Iceland, by middle school the Ricamora family had settled into the predominantly white Niceville, Flo. Though Ricamora loved to sing and dance, in his teenage years he started playing tennis to avoid being bullied. “There wasn’t even a drama club in my high school,” he recalls. “It was a very macho culture; there was no outlet for acting, singing, and dancing.”

Though he was good enough at tennis to win a college scholarship, Ricamora was still a target because of his ethnicity and his sexual orientation. He would sit in the front of the bus on the way to school so that he wouldn’t be bullied. “My best friend made fun of my race and I went along with it because I didn’t have anyone else to hang out with,” he says.

At Queens University in Charlotte, N.C., Ricamora earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology in 2001. During his junior year, he took an acting class and he was assigned a monologue from Lemon Sky by Lanford Wilson, in which a young man talks to his estranged father; Ricamora’s own mother had walked out on the family when he was a baby. “I just remember reading it thinking, Oh, I don’t even have to act, I could just be saying this myself,” he recalls. But he also realized that through acting, he could channel something universal. “It was so fulfilling to me to be in a room with people who are struggling to give insight to humanity through fiction, through characters.”

After college, Ricamora did local and community theatre in Charlotte and then in Philadelphia, working survival jobs and doing shows for little or no money. It was a grind but also exhilarating; for the first time in his life, he didn’t need to hide his artistic side to fit in. Even when he wasn’t working, “I would get my friends together to read Shakespeare aloud and I would cook a big pot of pasta for all of us,” he says happily.

In 2009, Ricamora enrolled in the University of Tennessee, where, with the use of the Alexander technique and therapy, he was able to work through some of his trauma. “When you go through acting training, it’s all about opening up and releasing and being an open vessel,” he explains. “But you can’t open up when you’re holding onto past trauma.” Throughout our conversation, Ricamora reiterates how theatre saved him; in addition to giving him a community, the process of “being a better actor saved my health, because I wasn’t carrying [trauma] around and being knotted up.”

Ricamora got his acting MFA in 2012 and in 2013 was cast in David Byrne’s Imelda Marcos musical, Here Lies Love, also at the Public, in which he played freedom fighter Ninoy Aquino. The performance earned him a Theatre World Award and he reprised it in 2017 at Seattle Rep. It was the first time Ricamora realized that Asian actors didn’t need to hide their ethnicity—that they could be heroes of the narrative.

“I could see that we were funny and beautiful and smart, and witty, and cool as fuck,” he remarks. “It made me accept myself and my skin and my own heritage in a way that I never felt like I could before because I was the only one in the room.”

In 2014, Ricamora was cast in a bit part in “How to Get Away With Murder.” His character, Oliver, was supposed to die in the pilot, but show creator Pete Nowalk was so impressed by Ricamora that he was kept alive, and became a series regular in Season 3 (his mother on the show is played by award-winning Filipino stage actor Mia Katigbak).

In 2015, Ricamora made his Broadway debut as Lun Tha in Bartlett Sher’s revival of The King and I. Ricamora talks about the show with some hesitancy. He loves The King and I for the music, but he is hardly unaware of its problems.

“They sat us down the first day of rehearsal and they were like, ‘We want this to be really authentic, we don’t want caricatures at all of anyone.’ Which was great, because then I felt like I could be—” And here he pauses, almost as if he’s realizing he isn’t doing publicity for that show anymore. “Lun Tha is just not very—he’s not written out, there’s nothing there,” he says with a sigh. “So you come in and the entire time you’re onstage, all you’re trying to do is get Tuptim to leave with you. And you don’t know why, you don’t know how you fell in love. You have to make it up for yourself.”

In Soft Power, David takes Xuē Xíng to The King and I (they even display the Broadway poster from the 2015 production). Despite the “problematic” elements, David admits that “at the end of the show tonight, I was still crying anyway.” The characters talk about the musical as a “delivery system” for influencing audience emotions.

But if The King and I is a show about Western dominance and Eastern exoticism, Soft Power’s aim is slightly more multifaceted. On one level, it’s to challenge the audience’s perceptions of what they think American values are. The show-within-a-show Xuē Xíng sings,

I was taught to be strong

We were hit if we cried

Who am I, to want more

Than my status and pride?

I’m happy enough

And Hillary (Alyson Alan Louis) answers with:

I was taught I could be anything I wanted

Even President of the United States

If I worked hard enough

Gave my all enough

So I worked

And I gave

To my people and my country

’Til I realize today

That there’s nothing left inside

I gave all of me away

And why am I so lonely?

I’m never enough

In other words: Is it worse to not want at all, or to want and not get it because the system is set up for you to fail?

“We live in a really uncomfortable time right now, and I think we should be challenging what we think and who we are as a country,” Ricamora replies. “That includes people who are conservatives and Trump supporters; we have to accept they are a part of our country.”

Soft Power dismantles the American mythos of democracy, freedom, and bootstraps, and to realize that its inner ugliness can’t be ignored any longer. It’s in the White House. Soft Power is a soul search, with songs (there’s even one about America’s destructive love for guns).

It also dismantles the assumption that a musical with an Asian cast can’t sell, as evidenced by the sold-out runs in three cities. Though Ricamora, ever the realist, is aware that it’s going to be an uphill battle for Soft Power to have a future life, including one on Broadway. Yet he’s cautiously optimistic; with films like Crazy Rich Asians and The Farewell, more opportunities are opening up for Asian actors to portray human beings, and not just cartoons. Ricamora is also currently developing a television show about gay Asian men called “No Rice.”

“What attracted me to acting is getting up onstage and speaking my truth,” he explains. “There’s basic human truths that live in all of us no matter our race or sexual orientation. And that’s still what I want to do and I feel like that’s what I get to do in such a big way in Soft Power. That’s the reason why I was like, when I started acting, this is my career, this is what I want to do with my life.” He pauses, then adds with a small, sheepish smile. “It feels like a noble thing to do.”