On the evening of April 14, 1865, well-known actor John Wilkes Booth entered Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., during a performance of Our American Cousin, presented his calling card to an usher at Abraham Lincoln’s box, was permitted entry, and fatally shot the president at point-blank range.

Last February Variety reported that during the climactic duel in Hamilton in San Francisco, an audience member had a heart attack, and the ensuing commotion led some others in attendance to believe an actual shooting was in progress. At least one audience member shouted, “Gun!” and attendees rushed to the exits. In the melee, three people were injured, including one person who suffered a broken leg.

Six months later and on the other coast, there were no injuries, but hundreds of people were terrified when, just before 10 p.m. on Tuesday, Aug. 6, according to a Twitter post from the NYPD, passing motorcycles backfired and “sounded like gunshots,” causing panic in Times Square and interrupting performances inside several Broadway theatres.

America’s toxic love affair with guns, attributable largely to an overly generous reading of the Second Amendment’s “right to keep and bear arms,” has spilled into every area of our public lives, taking countless lives and spreading hair-trigger terror. Though there have been tragic mass shootings everywhere from places of worship to shopping malls to movie theatres, live theatres have so far been spared such grim headlines. Unfortunately, barring drastic gun control measures, we can’t count on that exception holding.

Last year I attended a CPR training offered by the large presenting theatre where I work. At the end of the session, the emergency worker who led the training said, “We also do active-shooter training,” like a wedding singer at the end of the reception announcing, “We also do bar mitzvahs!”

Active-shooter training for legit theatre. Has it come to that? Apparently it has.

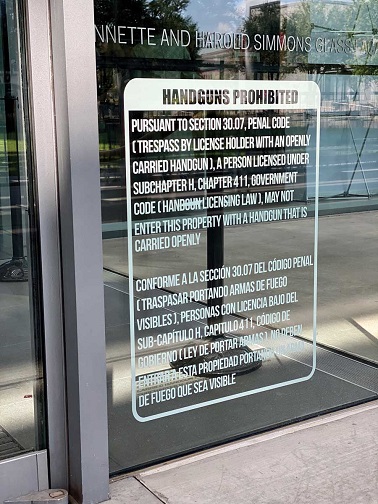

For a period of time not long ago, Dallas Theater Center’s website landing page had a surprising pop-up notification, stating that the “open carrying of handguns on the premises is prohibited.” As Jeff Woodward, DTC’s managing director, explains, “Texas statute does not allow most municipal facilities to bar weapons, and since the AT&T Performing Arts Center is owned by the City of Dallas, by law handguns were permitted, but are not permitted in, say, privately owned sports arenas.”

Chris Heinbaugh, vice president of external affairs at ATTPAC, provided details. “Although the ATTPAC is city-owned, the center’s nonprofit foundation manages and operates the venues; the city does not play a controlling role beyond providing some funding. The Texas Attorney General opined that because the city does not operate, program, or control the center, it does not qualify as a municipal building. This allows us to forbid open carry. Concealed carry is allowed, assuming one has a concealed weapon permit. However, that is not the case when education elements are involved. Between the center, its partners and five resident companies (including Dallas Theater Center), almost all of our performances and activities involve students. During those kinds of performances, we can bar concealed weapons, as well as open carry.”

Most states have open carry laws, allowing individuals to sport a firearm visibly, though in almost all 50 states, carrying a concealed weapon requires a permit. Pro-gun rocker Ted Nugent has made headlines with his insistence that audience members be permitted to bear arms at his shows. But in 2018 his own management reversed itself before a concert at Berglund Center in Roanoke, Va.. As the venue is city-owned, by law it can’t keep guns out, unless the artist requests a ban. Nugent’s contract always had the provision to allow guns, but in July 2018 Nugent’s security team was being more careful, given recent mass shootings. So pat-downs were performed at the entrance, and patrons with guns were asked to leave them in their cars.

“Christina Grimmie’s murder was a game changer,” says Christopher Jahn, production manager at the Broward Center for the Performing Arts in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. He refers to the terrible night in Orlando in 2016 when the 22-year-old YouTube and “The Voice” sensation was shot by an obsessed fan while she was signing autographs after a performance. That led to “security guards who do ‘wanding’ (with handheld metal detectors) at the front entrance,” Jahn says. “We don’t have metal detection gates yet. Also, a member of the Fort Lauderdale Police is always in the room during autograph-signing events.” Jahn adds, though, that South Florida’s smaller theatre companies have not updated their protocols.

If your theatre would like to know what precautions it should be taking, you could do what the State Theatre New Jersey did and contact your state branch of the Department of Homeland Security to request a threat assessment. The State made a number of changes based on the threat assessment it received a couple of years ago, and more are planned.

“The formula is: The more safety measures you have, the more inconvenient it is to the public,” says Jessica Trechak, State Theatre’s director of event services for more than 15 years. “We are always asking, how do you balance convenience vs. safety? Our security officers do bag checks at the doors. We don’t do pat-downs. We only do wanding if the artist requests it, and then we rent the equipment from a security supply company.”

She went on to explain, “We always have one or two armed police officers on site—two if the act is the type that tends to draw a rowdy crowd that may become unruly, like a heavy-metal band—from 60 minutes before curtain until the theatre is empty.”

There was a time when guns were prohibited at the State, even in the hands of security personnel. “I felt safer not having any guns in the theatre, because I worried, what if the gun fell into the wrong hands?” says Trechak. “In those days, we would ask anyone carrying a gun—usually an off-duty police officer—to put it in their car, where hopefully they have a lockbox. Now I have learned that it is preferable to let an off-duty police officer keep his or her weapon during the show. A mass shooting happens so quickly that by the time police arrive, it’s already over. An armed officer on site can neutralize a situation considerably faster.”

So around four years ago, State Theatre’s protocol was rewritten. If a security officer finds a gun in a patron’s bag, or if a patron tells security that they’re carrying a gun, the officer brings the patron to the officer on duty, who checks their ID and permit, and notes the location of the patron’s seat in case another patron sees it and brings it to the attention of the house management, or in the event of an emergency.

What about when guns are part of the show? Sometimes weapons are used in a stylized way, as with the slow-motion bullet fired by Aaron Burr in Hamilton, or in the opening of Chicago, in which Roxie Hart shoots her lover during “All That Jazz.” In the latter example, the gunshot sound is made by sharp, percussive strikes on a snare drum. According to a press representative for the current Broadway staging of the show, Heath Schwartz at Boneau/Bryan-Brown, the prop is “a replica of a silver, pearl-handled revolver. It’s not a real gun, but it has some weight to it and looks real. It hangs in a holster next to the conductor through the entire performance and is only used during that one moment.”

Says Jahn, “If there’s a gun that has been modified to shoot blanks in a show, the show should have a weapons master,” or armourer, “whose responsibility is to deal with the firearms. The weapons master teaches the director, actors, and stage manager how to safely handle the prop. As soon as a rehearsal is over or the curtain comes down, the weapons master locks the gun in a gun vault. The gun should never be on a props table. Either the actor has it, or the weapons master has it, or it’s locked away. Also, whenever an actor has to fire at another actor, the gun is never pointed directly at the person, but rather upstage of the person.”

As art reflects life, and mass shootings have come to loom so large in our consciousness, we are seeing more guns on our stages. These must be handled with sensitivity. One noteworthy new play featuring disturbing gun violence was presented last year by the Public Theater in New York and at California’s South Coast Repertory and Berkeley Repertory Theatre. In Office Hour by Julia Cho, gunfire figures prominently, and terrifyingly, in the play’s action.

Veteran fight director Rick Sordelet, who staged the gun scenes, says that this was intentional. “The director and the playwright wanted it to be as realistic as possible,” Sordelet explains. “They wanted the audience to viscerally feel the fear and the adrenaline, because they were creating a play whose purpose was not just to entertain, but to give the audience the opportunity to understand the psychological makeup of a shooter, to perhaps even open the eyes of people who are on the fence about gun control.”

Sordelet says the ceiling of the set was low, thereby amplifying the sound of the gunshots, enhancing the sensory impact. He has staged other violent scenes in which many more blanks were fired off than in Office Hour, such as the Public’s 2017 production of Julius Caesar at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park, where 80 rounds were fired off at the end of the show, or Daniel Sullivan’s staging of Troilus and Cressida the previous summer in the same venue, where 250 blanks were fired at each performance. In those cases the stage manager notified the NYPD 10 minutes before the scenes were to start, because invariably people called 911. Even with the preemptive call on the first night, emergency responders were dispatched.

Notes Sordelet, “Big cities like New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago have the strictest gun laws. At City Center in Los Angeles, I designed a report that when completed tells the police where the prop gun is at every moment.” He said that there needs to be more training on how to safely handle guns onstage, since they are appearing there more often. “The creative team of Office Hour wanted the audience to walk away saying, ‘Okay, this is serious.’ I think we achieved that goal.”

Lisa Lacroce Patterson, a freelance writer who has also worked as an arts administrator for 30 years, is a frequent contributor to this magazine.