Mark Larson's new book Ensemble: An Oral History of Chicago Theater (Agate Midway), tells the stories of the town's theatre in the words of its makers, from Steppenwolf to Second City to Goodman to Lookingglass. In Chapter 26, "We Are Here and We Are Part of Chicago's Story," Larson talks to artists from under-represented groups, including people of color and trans/non-binary people, about the challenges they've faced, and the opportunities they've forged, to make work on Windy City stages. This story is part of a package of stories about Chicago theatre; for more, go here.

Gregory Mosher (director; artistic director, Goodman Theatre, 1978–1985): I was thinking the other day that the real turning point of my time at Goodman Theatre was when we did Native Son [in 1978], my first production as artistic director. It’s a play set in Chicago with 35 Chicago actors, half of whom were Black. Chicago writer. Set in Chicago. Whole cast was Chicago. I adapted it with Mamet. It came about because I said to [actor] Meshach Taylor, “What do you think, Hamlet or Bigger Thomas?” He said Bigger, and that was that. I figured I might get fired if it didn’t work—it was big and expensive and angry—but it worked out. Amazing cast, that was.

I’m also proud that I think the Goodman’s Christmas Carol [1984] was the first interracial cast of Christmas Carol in America (if that’s true). I’m proud of it no matter what. I’m really proud of it if we were the first company to do it.

The New York Times covered the Goodman’s opening of A Christmas Carol that year, putting the cast of 27—eight of whom were Black, including Tiny Tim—into perspective. Chicago has had a long history of segregation, and not long before the opening “a Black family was terrorized and forced to flee from their new neighborhood on the West Side.” Mosher was quoted in the paper as saying, “There is no issue more on the minds of people in this city than racism…This doesn’t directly translate into a political statement, but it’s there in front of your eyes: 27 people creating a play together, oblivious to everything racial.”

William J. Norris (actor; original Scrooge at Goodman): Before the show even opened, the Goodman got letters saying, “There were no Black people in England back then! This is not telling the story!” Blah blah blah.

What we were doing was a seismic shift in how this story’s perceived and how theatre was going to be perceived from here on out. If Goodman had an intention [to make societal change] with this, fine, but I don’t really know what the intention was. I just thought they were casting the best people for the parts. I remember how excited I was when I learned that when Ernest Perry Jr. was cast as the Ghost of Christmas Present.

Ernest Perry Jr. (actor): But when we talk about all this, you can’t forget the contribution that Stuart Gordon had made with the Organic Theater [in the ’70s]. Stuart cast whoever was good. It wasn’t about “I’m casting you because you’re Black.” No: “If you’re good, I’m casting you.” I’ve always thought that’s the way theater should be.

J. Nicole Brooks (actor; playwright; director; Lookingglass ensemble member, 2007–): I was brought up by my mother and also my uncle, who was a Black Panther. I grew up on the South Side of Chicago. Fifty-fifth and State was the main intersection near us. I remember one time walking near the Robert Taylor Homes and looking up at those monolithic towers. I knew it was bad and that I couldn’t go over there. I asked my mom why it was like that, and she said, “It’s because the white man wanted to stack us up to see how quickly we would kill each other.” That’s what she said.

I think I became an artist because I wanted to buck back against every time people said no. I went to Carter Elementary School. And—I’m going to be frank, OK?—the schools were really, really fucked up. My eighth grade homeroom teacher was a big white lady who spoke with this affectation of, “I’ve been working in Chicago Public Schools with Black kids for a long time, so I ain’t scared of none of y’all.” I’ll never forget the day she looked at us, a classroom full of Black children with the exception of this white girl named Prudence Gearhart (love her) and said, “Y’all got three choices. You can apply to Englewood, DuSable, or Dunbar. The only people that can apply to other high schools are Prudence Gearhart”—and this other guy who was our valedictorian, a guy named Andre. But for the rest of the graduating class—we’re talking like a hundred kids—we were told we had those three choices, [which] at that time were the worst schools in the city.

I applied to Curie, which is a performing arts magnet school, and two others [that I knew were mixed race]. I interviewed, auditioned, got in Curie, and it changed my life. I became a drama major and I studied theatre, dance, and music. I was at school from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. every day. It led me to the city’s cultural heartbeat for young people, and I never let go of it.

My first professional productions in Chicago were at the Court Theatre. I did Midsummer Night’s Dream [1999]; I did Phaedra [2002]. It got me into that canon. But when Ron OJ Parson started to direct down there and was doing all of these August Wilson pieces, I was like, hallelujah! Because I was tired of being the only fly in the buttermilk.

Charles Newell (director; artistic director, Court Theatre, 1994–): In 2008, I thought, Charlie, you’re not really serving your local community. Despite having cast actors of color as leads in Beckett plays and Barber of Seville and Cyrano de Bergerac and other shows, the percentage of our audience of color was only five or seven percent. So I thought, well, as a director, I can keep trying to find a way to look at work through an African America perspective, or I can do something more aggressive.

So I did two things. One is I said we need to expand our definition of classic theater [which is what Court had been about] to include the African America canon. The second thing I did was that I hired Ron OJ Parson as our resident artist. Beginning with Fences [in 2006].

Ron OJ Parson (director; resident artist, Court Theatre, 2007–): When I directed Waiting for Godot at Court [2015], we were doing it during the Ferguson [Uprising] and [the choking death of] Eric Garner [at the hands of police in 2014]. So when Vladimir and Estragon, as Black people, say, “I can’t breathe,” it had a different meaning. It was deeper. Waiting. We were waiting. What are we waiting for? We were waiting for Godot. We were waiting for peace. We were waiting for justice. We were waiting for salvation. We were waiting for a lot of things, so it had more impact. That’s what theatre is supposed to do, so when you do a thing differently, when you take a different approach, it can move people differently.

When we did Caretaker up at Writers Theatre [2011], we had two South Asian guys, Anish Jethmalani and Kareem Bandealy, two of the best actors in the city. Anish told me afterward, “Man, when I saw it on the season, I didn’t think they would have anything I could audition for, so when they called me, I was shocked.”

I don’t believe necessarily in blind casting, but I believe in nontraditional casting. By that, I mean there are a lot of plays out there that can be diverse in casting because the story is not about the race.

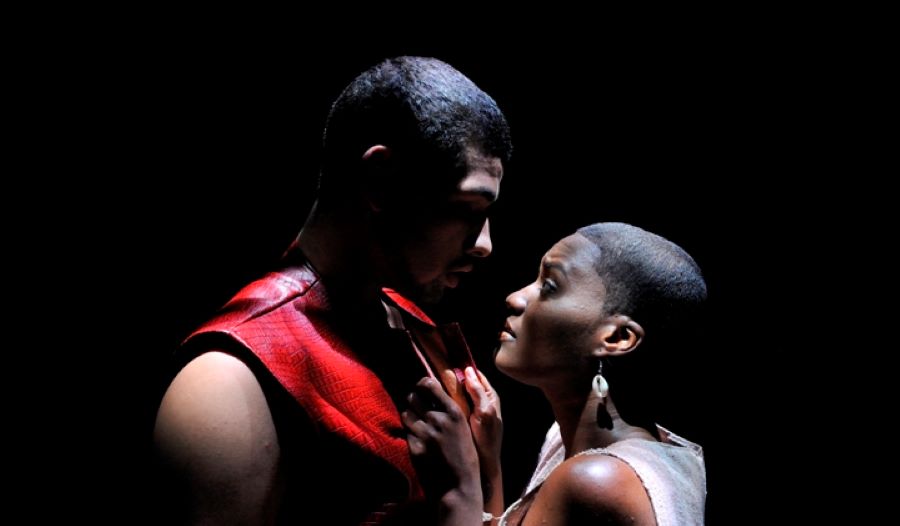

Lili-Anne Brown (actor; director; educator): When [Bailiwick Repertory Theatre] did Aida [in 2010], the director wanted to do what I laughingly call “traditional casting” of the show. I laughingly call it traditional casting because there’s a lot of arguments about that. All that traditional casting really, technically, means is “how it’s always been done before,” or “how it was done originally on Broadway.” For whatever reason, Aida [the 1998 musical by Elton John and Tim Rice] was always done where the Egyptians were played by Europeans, which I find hilarious and wacky. When it was done the first time, why weren’t people like, What? What? What? You know where Egypt is? Is no one paying attention? Is no one going to say, what the fuck is this? Why is it even tradition? And how traditional is Aida? When did it come out, like, the ’80s? Really? It’s a sacred cow already? It just has to be done once to be tradition? That’s crazy. I was the casting director, and we were slated to do it the same old same old. I said, “Excuse me. No.” I became very stubborn and intransigent and refused. “No, everybody will look like they’re from Africa in some way.” They were like, “Well, you made your point. Go for it.”

Then the task became to find all these damn Africans I said I was going to find. It was super difficult, super difficult. They weren’t coming out. Guess why? Because how is Aida traditionally done? We posted the [audition] notice, and here come all these white girls. Black people were like, “I’m not in that” (except for the chick that plays Aida and her brother). So we had to put out another notice: “No, you are in this. Please, please, please, please, please, come.” Some more people showed up, but it is a big cast, so this was still not enough people. We did four different open calls and, boy, was everyone annoyed with me. I was annoyed with me. We were saying, “We have to try harder. We have to try harder. We have to do more.”

Now, this is why Bailiwick is so special to me, because instead of saying, “Okay. We tried,” the then-artistic director, Kevin Mayes, said, “You have a point, so if you really think you can accomplish this, I will rent another audition room for you and we can do this again.”

In the end, we got some people that drove up from Peoria. They do some kind of crazy, amazing community theatre there that’s stellar. Who knew? So we had this gorgeous, amazing cast that did look like a spectrum and did look like, yeah, all these people could be from Egypt and all these people could be Nubians. It was different than anyone had ever seen. Chris Jones gave us three stars with our zero budget. He was like, “Yeah, why hasn’t it always been done like this?” I was like, “Exactly.” We felt so victorious.

Here’s the thing. I had been wanting to do something like that for years. Somebody just finally let me. Finally somebody said, “Okay, do it.” Whereas before, it was always, “Shush!”

Emjoy Gavino (actor; casting director; founder, Chicago Inclusion Project): I had an audition for Wait Until Dark at Court [in 2009], directed by Ron OJ Parson. I loved that role; I connected to the role, and I loved the genre, and I loved the material. I knew I could do it, but I thought, I really would like to get this, but there’s no way. I went to the audition, and I saw a lobby full of these beautiful blond actresses, many of whom looked like what you would expect to see in that part. I was just like, this is a long shot, but I’ll let them see what I can do because I know I can do it well. But then when I got the call from my agent that I got the role, I was full of doubt: Why did I get this role? Were they specifically looking for an Asian person?

I didn’t trust it. I had been conditioned to expect that I could only have a certain career and a certain trajectory. I honestly don’t know that I even enjoyed doing the show because I was questioning it the whole time: Why am I here? Do I deserve to be here? Are people watching me thinking I shouldn’t be there? What is Court thinking? What is Ron thinking?

I asked him one time. Why me? He told me, “I didn’t want to have an all-white cast. I didn’t want to do that Wait Until Dark. I wanted to do my Wait Until Dark. And you were the best for the role. This is what I wanted to do.”

I needed to go through the whole run to realize, oh my gosh, I can dream so much bigger than I have been dreaming, and that I’ve allowed myself to dream, and that my résumé does not need to look like every Asian actress’s résumé in the country. And I thought, if I had had the chance [when I was first starting] to see someone who looked like me doing this, that would have made me think that I could do it too. It was that role that switched my focus, and I started being more assertive about getting myself in rooms for plays that weren’t set in China.

A couple years later, I was talking to an older white theatre director about things that we’ve done, and when I mentioned Wait Until Dark, he said, “Oh, were you in the multi-ethnic Wait Until Dark?”

I said, “I was in Wait Until Dark.”

Ron OJ Parson: To be honest, when I cast Emjoy in Wait Until Dark, I think that sparked her. That’s what we want to do. [Pauses.] See? I’m a crier. I have to cry when I think of this. I think Emjoy had been inspired by that experience to say, “This should happen more often,” and [maybe that’s why] later she started the Chicago Inclusion Project.

Founded in 2015, the Chicago Inclusion Project “exists to facilitate inclusive experiences and hiring practices throughout Chicago theater.”

Emjoy Gavino: I’m friends with directors and playwrights, and when I wasn’t getting work, I said, “Can I just sit in your audition room, can I be a reader, can I get you coffee? I just want to be useful. I might want to learn another trade.” I thought maybe I’d like casting, I didn’t know. Being on the other side of the table, what I learned was that people in those positions, at that time, didn’t know where to find minorities. Or they didn’t think that they had the chops. Mostly, they didn’t think they existed, and because it was hard to find them, they didn’t make the effort.

There was one particular audition room where the director said, “You know, this is a very white group of people so far,” and the casting person said, “Well, there aren’t that many minorities in Chicago.” I was flummoxed.

But it’s like people who grow up together. You know the people that you know. Your circle is small. But you have to want to make your circle bigger, and I did not see the desire. Some of it is laziness, and some of it is just complete, total ignorance.

That night, within two hours, I sent that person 50 names of people that they hadn’t thought of yet. It just made me so angry. As an observer, I realized, this is what happens behind the table, and this is why it took me so long to get to the point that I was at. It pissed me off.

Well, you can’t wait around for other people to do something. Ben Chang, another actor in Chicago, and my friend Elana Elyce, the founding members of the Chicago Inclusion Project, all had also been disappointed in the community. They were my venting partners, among others. We talked about it for like six months: “How about we do one reading somewhere with a lot of cool people that never get to work together?”

Delia Kropp (actor; director; trans advocate; company member, Pride Films & Plays): It was a staged reading at Victory Gardens, directed by Chay Yew, and cast largely with people of different ethnicities and races, just to demonstrate that this is possible, you know? To get casting directors and artistic directors to start to think, this is the world now. It includes black people and Hispanic people, it includes transgender people, like me, and you can make the world on the stage look like that. This was a seminal moment for all of Chicago theatre. It was gigantic.

Of course everybody thinks of Christmas Carol at the Goodman. They have been casting that show racially diverse, as well as other shows, for years, and providing opportunities certainly for Asian Americans, Hispanic Americans, Black Americans. But that’s different from what we’re doing. We really want all races but also all gender types, as well as people with all abilities.

Emjoy Gavino: In 2017, the Inclusion Project partnered with the Goodman and a few other theatres and held unified generals, where you have a crap-ton of casting directors in one room, and an actor goes in and does an audition for all of them. We put together a list of the actors that we thought had been underrepresented in our community; either they had never been seen before, or they’ve only been seen doing certain types of roles.

When I wrote the audition invite to the actors, I said, “When you prepare your two monologues, think of a piece that you can do really, really well, and then do a piece that you don’t think you would ever get cast as, but that you dream of doing.” I had Ron OJ Parson in the back of my head saying, “You are more than what you think and that others think you are.”

What we saw was magnificent. When people walk into an audition in front of Steppenwolf and Goodman and Chicago Shakespeare, and say, “This is who I am, not who I think you want me to be, this is who I am,” it’s a game changer.

Nancy García Loza (playwright; co-creative director, Alliance of Latinx Theater Artists [ALTA]): The first convening of ALTA in 2010 invited a breadth of Latinx theatremakers and practitioners from across the city, and it was a social gathering. In the first year, they had different professional development workshops focused on and geared toward actors, stuff on auditioning, stuff for casting, on-screen performance. I met them later in August of 2012. They asked me if I wanted to join the leadership team.

I had heard from [co-founder] Tanya Saracho that different casting agencies in Chicago and different talent folks kept reaching out to her to say, “Hey, we’re casting a show, and we’re seeking a Latina XYZ.” So she was like, “You know what? This really makes me wonder. I’m a practitioner and I’m not a casting person, so if there’s this need here, what’s a way that we can organize some kind of framework around a member-driven organization that is here to serve as professional development, and a place where if you went to it, you’d be like, ‘Here are the Latinx actors that you’re seeking,’ without going to someone for whom that’s not even what they do for a living and asking them to send you their list?”

Isaac Gomez (playwright; co-creative director, Alliance of Latinx Theater Artists): And that’s what ALTA’s always been about. We as Latinx practitioners have evolved, even within the last 10 years, in that what you’re starting to see is a surfacing of millennial practitioners who…it’s not that they’re resistant to writing plays centered on the experiences of our racial or cultural identity, it’s that they want to do so in a way that occupies their equally-as-valid American identity.

Nancy García Loza: I think that our work with ALTA is a really great example of taking some of maybe the pain and doubt of where are we at right now and saying, “Okay, but I don’t have too much time to sit in my tears. I need to move, and we need to activate, galvanize, and organize as Latinx theatremakers, so that our stories are out there.”

Now when someone arrives in this city, and they’re like, “I just came in from El Paso. I’m a playwright or I’m an actor. Who do you know?” we can say, “Here are the 20 theatre artists in Chicago who also want to have coffee and talk about plays.” The point is that we are here, and we’re part of Chicago’s story.

Isaac Gomez: It’s about being undeniable.

Ike Holter (playwright): I think the city knows it’s a work in progress, and I think that’s exciting. Some cities think that they are all the way there, whereas Chicago is always, I think, cautiously moving toward progress. We’ve fallen some times, but the idea that we’re not at the end point is important, I think. That’s what the best cities are, I think, they’re always changing and hopefully trying to get better. Chicago has a feel of, okay, cool, so we’re all working on this, we’re all doing this, right? Instead of, like, it’s done, everything is great. No. Everything’s not great. We can be as mad as we want about a particular thing that is wrong, but the problem is systemic. So even if you fix this one boo-boo, you have a big scar that’s going to take a long time to heal.

Art is our activism. Theatre, I think, is an incredibly accessible art form, but a lot of people had taught that we weren’t allowed in that room. I grew up in the ’90s and I still was like, can I go there? Is it going to be okay? But the next generation, I want them to have it easier. I don’t want them ever to have [to deal with] someone, like a critic, who has the power to hurt their career because of the way that they look, which is something beyond the talent that they possess. I think about that stuff a lot. It’s like, I’ve survived this, and I deal with my own psychosis about the way I’ve been treated, etc., etc., but I want the people who are 10 years down the road not to have that, and then for us to have a conversation later about how it’s changed.

I know that the city of Chicago is now a majority-minority city. It is 60 percent people of color, and I think it is not inconsequential to notice that the best theatre in the city is made with people behind the helm, having the power, who look like the city. I think that’s when not only the audience grows but you get a next generation of people who are not just excited to go to theatre but see it as an active part of their lives. I think that makes them better people.

Sandra Marquez (actor; director): I’ve worked my ass off for 20-something years, so I’m in a position now where not only can I say things, but I have a responsibility to say things. Those things that I say are not always met with warmth. If I give you some examples, I’m going to be revealing names, and I’m not sure that I can do that right now. But, here’s an example I can give you.

My agent had called me and said, “Hey, [the Court] wants to see you for Clytemnestra for Iphigenia.” Well, when I was in school, I really loved doing classical theatre, so that was going to be my thing, doing classical theatre. Little did I know that when I got out, I would not be called in for those auditions. That’s a whole other story.

So when I got called into this audition, I was over the moon. My agent said, “There’s not going to be a callback, so go in and really do what you do. They’re going to cast it off the first audition,” which is kind of unusual. So I prepped hard for that audition. I was so excited. This was one of the rare times in my life where I walked out of the audition and thought, if they don’t hire me, they’re stupid. I knocked it out of the park. And I knew they liked it, too.

A week or so later, I get a call saying, “There’s going to be a callback.” I said, “Really?” So I prepped for that. I felt good about it. Then I get a call, “There’s going to be a third callback.” That’s when I realized, oh, I know what’s happening. They really like me, but they don’t know if they can cast me. They’re not sure if they can cast a brown woman.

I went into the third audition. When I finished, Charlie Newell said, “Sandra, can I be honest with you?” I said, “Absolutely.” He said, “Have a seat.” That doesn’t usually happen at an audition. Charlie says, “I’m just going to be honest with you. From the first audition—and I think you probably felt it—I just really liked your Clytemnestra.”

I said, “Well, you know, Charlie, it’s one of the few times in my life where I felt great about an audition. I really want to do this.’“

“Yeah, I hear that,” he says, “But I don’t know how to cast around you. I really don’t know how to cast around you. And I don’t believe in colorblind casting. I think it’s confusing to the audience.” I said, “Okay. Well, can I be honest with you?” He said, “Yes, of course.”

“Okay. First of all, when you put two people onstage, the audience already knows that I’m not really the mom and that’s not really the daughter. That’s the convention of theatre. No. 2, as a Latina, I know and I live in a world in which we come in many different colors. Even though the average American doesn’t realize that we are all colors, we know it. In my own family, my mother happens to be a light-skinned Mexican. My father is an indigenous-looking Mexican. So in my own family, I would not be cast in a commercial or in a film or in any TV show with my own real mother, because what the audience expects is something different. That’s the reality that I live in, so when somebody tells me that skin tone is going to be an issue, it boggles my mind.

“But I want to say also that if we in the arts aren’t leading this, then who the hell is going to lead it? It seems to me like that’s our job, that we should be cutting edge, not trailing behind.

“At the end of the day, you have to do what you’re comfortable with. I really want to thank you, Charlie, for letting me speak my mind about this, and I want to thank you for being honest about it, because 99.9 percent of the time, people aren’t. This is the first time somebody’s had the honest conversation with me. For 20 years, I walk into an audition room and suspect that’s what’s going on, and somebody says, ‘Thank you so much for coming in,’ and I walk out the door, and we never have the conversation like we just did. Thank you for having the courage to have the conversation.”

I walked out of the room, and just knew that I had kissed that role goodbye. I thought, you know what? At least I’ll go to bed tonight knowing that I said what I needed to say.

I was shocked when I got the role. I was absolutely shocked. [Pauses.] I’m getting a little emotional now talking about it…but this is the reality of being a person of color in this field. It is exhausting. But to know that I had that conversation, maybe that means that somebody coming after me doesn’t have to have it. Then I’d know I’ve done something. And I really have a deep love for Charlie because at the end of the day, it takes courage to be honest on both sides of the conversation.

Nambi E. Kelley (playwright, Native Son): After high school, I auditioned for the DePaul acting program, and I didn’t get accepted. But they offered me a scholarship to go to the theatre school. Well, I didn’t have much fun. To me, the theatre school, at that time, was very…there were no Black people, and I had come from a very multicultural environment. Now I was the only Black girl in my whole class. There was another gentleman there, but he was an acting major, so there was no one else of color in my program, and I found that really hard. I never said anything about my discomfort. Sometimes, in class, if something was really, really racist, I might get up and go to the bathroom, but I never raised my hand and called a teacher out on anything, ever. I would just get up and leave. Those were different times, you know? This was ’91 to ’95. I wanted to get out. I hated it. I hated it.

Now it’s 2018. Goodman is running Enemy of the People. I had tickets to the opening night because I’m on their opening night list. I was flying in that day. I got off the plane, and wondered if I really wanted to go. But I jumped on a train, I put on lipstick, and I got to the lobby. Roche [Schulfer] was there. He’s like, “Hurry up, it’s starting.” When I walked into the theatre, my seat was in the middle of all of their artistic staff. So, I’m sitting behind Adam Belcuore [casting director, 2003–] and Henry Wishcamper [artistic associate] and Steve Scott [associate producer, 1980–2017], and I’m thinking, you sat me…in the family section? I was so floored, and so deeply touched, you know? It may have been random, but even if it was random, it was still like, all right: I was supposed to be here tonight. I had been planning to go home from the airport and hang out with my cat. But I was supposed to be here.

Reprinted with permission from Ensemble: An Oral History of Chicago Theater by Mark Larson, Agate Midway, August 2019.