This story is part of a package of stories on Chicago theatre. For more, go here.

Chicago storefront theatre has a distinct mythology: A group of friends assembles with a dream of turning the theatre scene on its head. Often young and impressionable, they’re confident that Chicago will be the city where all their dreams come true.

Sometimes it’s a Cinderella story that ends with popping champagne, as when in 1974 a group of actors including John Malkovich and Gary Sinise launched Steppenwolf Theatre Company, birthing a Tony-winning Equity house with a star-studded ensemble, several theatres, and a swanky bar and coffee shop open six days a week. Or it’s a smaller-scale success story like that of A Red Orchid, cofounded by Oscar nominee Michael Shannon in 1993, which retains a storefront just down the street from Second City, staging quirky productions with actors a breath away from the audience.

Other times the dream doesn’t come true—or it does, but only for a while. Many factors can tear a company apart, but most often a lack of funds overwhelms simple fantasies with harsh reality.

What exactly is “storefront theatre”? There’s no building requirement, budget limit, or seating capacity. Whether traditional black boxes or nontraditional spaces, often in residential neighborhoods, Chicago storefront theatre prides itself on more intimacy, as well as edgier material, than an audience member can find in a Broadway touring production or the city’s larger venues. Storefront theatre differs from community theatre, not in its meager starting budget but in its aspiration that those involved strive to be professional working artists. Even if they don’t make a living doing what they love, they are making a life (and some money) in it.

Storefront in Chicago is such an institution that the Joseph Jefferson Award, which annually honors local theatre, has a separate ceremony for non-Equity Awards (though storefronts can attain Equity status as well, and many do).

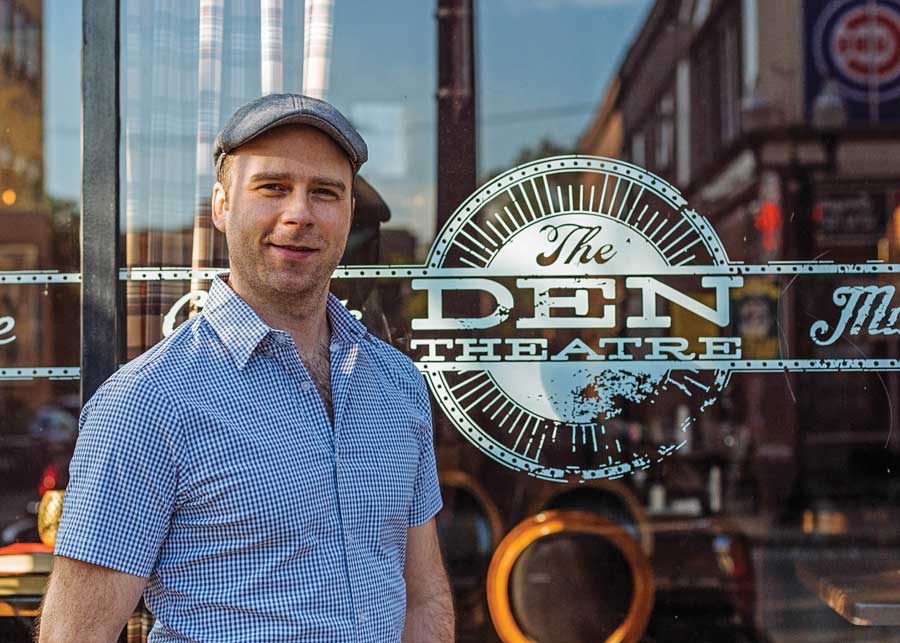

“The heart of Chicago storefront theatre is being brave,” said Ryan Martin, owner of the Den Theatre in Wicker Park. “It’s leaving no stone unturned to do high-quality work. It’s scrappy.”

Martin moved to Chicago in 2002 to act, but after years of “mostly playing small parts that a million other people could do as well as me, if not better,” he turned to producing in 2010. With William Inge’s Bus Stop in hand, he rented a second-floor theatre space. “I bought some curtains and chairs and lights with the little money I saved,” he said. “I only had enough to get through two months.”

Martin has since expanded the Den to adjoining buildings containing multiple black-box spaces as well as bar, cabaret, and café spaces “to make people feel free to hang out and talk about the art they just saw.” The Den has five storefront companies in residence who commit to producing a certain number of shows per year. Martin still rents the space—with a 30-year option to renew, so he’s not going anywhere—and runs the Den as a full-time, for-profit business. It has three revenue streams: producing theatre and comedy, rental from outside entities, and food and bar sales. He has 25 employees (including a general and operations manager, a food and beverage manager, box office and bar staff), plus investor and co-owner Carol Cohen, who also founded Haven, now a Den resident company. Martin plans to keep the Den a for-profit organization for the foreseeable future. “I produced Bus Stop on a credit card, and no nonprofit board would’ve let me do that,” he said. “When you don’t have proof you can do something, the only way is to just jump in.”

Peter Moore knows ALL about jumping in. Now artistic director of Steep Theatre Company, he remembers when he was one of three friends putting on a show and battling the music next door.

Moore launched Steep in 2001 with two classmates from Steppenwolf’s acting school, and in 2003 they found a performance venue two blocks from Wrigley Field. “It shared a wall with a bar that had live country music every Friday and Saturday at 9 p.m.,” recalled Moore with amusement. “Sometimes it worked, but if the show was set in Vichy, France in the ’40s, Johnny Cash didn’t play so well.”

After five years Steep moved to a space in Chicago’s Edgewater neighborhood, just underneath elevated Red Line train tracks. Since 2008, their theatre’s production capabilities have grown to include a second space called the Boxcar, a bar and cabaret where the audience is invited to mingle with cast and designers.

Earlier this year Steep became an Equity theatre—all according to plan. The ensemble has grown to 45, including artistic associates. Many are now Equity actors or close, Moore said, which severely limits their involvement with non-Equity actors.

As executive director Kate Piatt-Eckert put it, going Equity isn’t just about compensating the artists; it’s a “shift in the business model.” In 2012, Steep brought her on as a full-time staff member, and one of her jobs was to help increase contributed revenue. (The company’s only full-timer, Piatt-Eckert described her office as “a tiny room where we store a bunch of things that we’ve reconfigured a thousand times.”)

Steep also focused on increasing revenue streams by opening the Boxcar. But the Equity tipping point was a three-year grant from the Bayless Family Foundation, which meant “we were able to make that move now while laying the track for the future,” Piatt-Eckert said.

Despite its triumphs, Steep still pounds the pavement to find audience members for its 60-seat house. “It’s remarkable—we’ve been in this neighborhood for 11 years, but I know people who live nearby and don’t even know we’re here,” said Moore. Adds Piatt-Eckert: “There can be 40 shows in Chicago tonight, and it’s hard to convince someone based on a two- to three-sentence blurb.”

Unlike Piatt-Eckert at Steep, Broken Nose Theatre artistic director Elise Marie Davis isn’t paid for her administrative work. She hopes that will change soon, but for now she and the rest of the theatre’s six-member staff are volunteers with two priorities: to pay their artists (which many storefronts prioritize over compensating staff) and to make sure anyone can see their shows. Which is why Broken Nose has a pay-what-you-can structure for its productions.

This accessible ethic was tested during its most successful production, the 2017 Midwest premiere of Michael Perlman’s At the Table, which follows a diverse group of college friends who gather for a weekend retreat where funny, provocative conversations and confrontations ensue. It was a smash, with the Chicago Tribune’s Chris Jones calling it “one of the most riveting shows of the theatre season.” After winning four non-Equity Jeff Awards, Broken Nose remounted At the Table that summer at the Den Theatre.

“We had this realization that we could do one of two things,” Davis said. “We could either say we are still pay-what-you-can, or we could charge $40-60 and every seat would still be filled.” Despite the promise of more income, the vote for the former was unanimous. “Regardless of any hit show, we still want those individuals who can’t afford a ticket to witness it. This was us putting our heels to the ground and saying, this is who we are.”

Since At the Table, Broken Nose continues to stage thought-provoking work on the second floor of the Den, where they are now in residence. For the once-itinerant company, having a home “is nice for our own sanity,” Davis said. “I’m excited to continue to play.”

Not every storefront continues to play. Companies disband as frequently as they form. Perhaps the most notorious was Profiles Theatre’s shuttering in 2016, only days after the alt-weekly Chicago Reader published an exposé of the storefront company’s history of poor working conditions and relentless sexual harassment of its young actresses. The advocacy organization Not in Our House was born in part from this controversy, and the Chicago Theatre Standards its members created was intended as a code of conduct for non-Equity theatres, where there typically aren’t oversight structures in place to deal with abuse and conflict.

Egregious scandals aside, most of the time small theatres shutter due to burnout and lack of funds—which makes them not too different from their larger counterparts. Sean Graney launched the Hypocrites in 1997, and over the next two decades the company gained Equity status, critical acclaim, and a devout following. Its production of Our Town, directed by Tony winner David Cromer, moved Off Broadway in 2009, and Graney’s All Our Tragic—a 12-hour mashup of all 32 Greek tragedies—garnered six Equity Jeff Awards in 2015, the company’s first year of eligibility.

But the Hypocrites are now on hiatus, and, according to a board member, plan to officially disband once final audits and paperwork are complete. The company’s 2016-17 season ended early in part due to declining ticket sales, and the 2017-18 season comprised just three productions. Always an ambitious company, it seems that the Hypocrites’ increasingly elaborate production values may have finally outrun their finances. (Graney declined to comment for this article.)

“The culture of the theatre world is not conducive to small nonprofit theatres,” said Lindsay Bartlett, former artistic director of the now-defunct 20% Theatre Company. “We are trying to compete with some mega-theatres, and they are taking up a lot of space—literal space as well as grant and foundation monies.”

Founded in 2002, 20% had multiple ensembles in Chicago and Minnesota’s Twin Cities (the latter still thrives). The Chicago branch concentrated on “women-led feminist theatre,” as Bartlett called it. A company highlight was its 2016 production of Anna Ziegler’s Photograph 51, about scientist Rosalind Franklin. “Tickets jumped off the shelves,” Bartlett said. “Everything came together: our first Jeff Recommendation, the community connection with Rosalind Franklin University. And we performed in the basement of a church with an awesome artists’ community in their congregation.”

Sadly, Bartlett said, the company’s brand lost its uniqueness. “The feminist [angle] was very hot-button when we started,” she said. “But then a lot of people started doing feminist theatre. We lost our audience base, and with that we lost the money.”

It didn’t help that Bartlett was leading the company while holding down a day job. “I was inundated with my day career and letting the theatre slip,” she said. The company folded in 2018. Since then, Bartlett has worked as a dialect coach in the Chicago suburbs, but she looks back fondly on her time with 20%. “I’d love to be part of Chicago theatre again. Someday. Maybe.”

Even the more successful storefronts have their struggles, with finances topping the list. “Every year we try to generate more income while focusing on artistic innovation and then balance the competing goals for every dollar, such as pay artists more, spend more on production materials, and make much-needed improvements to our space,” said Steep’s Piatt-Eckert.

What’s more, as in other major cities, many funders require applicants to meet a minimum budget requirement. For small companies without a fundraising department, finding financial resources is a challenge. “The Bayless Family Foundation is great,” Davis said of the grant that allowed Steep to achieve Equity status, but to qualify, the theatre’s budget “has to be a quarter of a million.” (Davis didn’t disclose Broken Nose’s exact budget, but described it as “less than six figures.”) She credited her “work wife,” Broken Nose managing director Rose Hamill, for recruiting volunteers to research and secure new grants. “Ninety percent of people don’t join theatre to write grants,” Davis said. “It’s a very thankless job, but helps us immensely.”

Davis also emphasized the importance of cultivating individual donors, even those who give a few bucks at the end of a performance. “A lot of audience members don’t realize that when we’re saying ‘your donations help us,’ we are stating facts,” she said.

Despite being mostly non-Equity, storefront artists look out for each other. Both Broken Nose and Steep follow the Chicago Theatre Standards, which address everything from facilities to rehearsal process to stage violence, all in the name of artists’ safety. Thanks to the standards, according to Piatt-Eckert, the Steep now makes sure “that our artists have direct lines of communication with our staff and our board and that everyone’s voice and experience is valued and respected. Transparency and communication keep everyone safe.”

Despite the day-to-day and long-term challenges, many of the artists who spoke for this article relish their small status, and are feeling optimistic for the future of their companies.

“You give us two flats, two chairs, and a table, we’ll figure out creative ways to use them for maximum effect. And that, to me, is extremely exciting,” Davis said. “I think of Chicago storefront culture as resourceful as much as it is scrappy. Some of my favorite shows in the city have been with minimalist sets or using found objects.”

Or, put more succinctly by Steep Theatre’s Moore: “No matter the obstacles and constraints, I’ll take scrappy.”

Lauren Emily Whalen is a 2018 alum of the National Critics Institute at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center, an Equity Membership Candidate, and author of the YA novel Satellite. She lives in Chicago.