That Oklahoma! received its world premiere in 1943 may be a piece of musical theatre trivia for many people, but not for my father. My dad was born that year—a photo from the show’s auditions was published on the day he was born, and the cast went into rehearsal 12 days later—and as a result he has come to feel a special connection to the Rodgers & Hammerstein musical, an attachment that even cognitive challenges brought on by a combination of Parkinson’s disease and a recent stroke couldn’t diminish.

My dad, a radiophile and retired educator, was diagnosed with PD in 2005, and though he experienced a gradual decline over the following decade, he managed independently and oversaw his own care until a stroke two years ago last month. Immediately following that additional trauma, his cognitive and physical difficulties increased significantly, and it has been a struggle to put his life back together and keep it together. He now needs 24-hour care—we’re fortunate to receive services that provide a professional live-in caregiver—and though his doctors are confident he has the ability to walk, and though he’s working toward greater mobility through physical and occupational therapies, whenever he leaves the house he spends most of his time in a wheelchair.

Due to his condition, he has good days and bad days, good hours and bad hours, cognitively, physically, and emotionally, and his demeanor can change dramatically in relation to a variety of factors that are often hard to predict. So when he heard about Oklahoma!’s current Broadway revival on the radio and asked if he could see it with me, my heart sank. There was no way I could bring him.

A few weeks later my dad asked if I’d arranged for us to see the show, and I told him I was looking into it, still sure it wasn’t feasible for us. I discussed my disappointment with a friend who works in commercial theatre, and she was adamant that I take my dad. She reasoned that especially given that the production features Ali Stroker—who would become the first wheelchair user to win an acting Tony—it is imperative for the theatre community to make shows accessible, regardless of patrons’ obstacles and abilities.

Before my dad’s stroke, going to the theatre together could be a challenge but didn’t require much in the way of special planning: We’d take the train from Long Island, leave extra time to get from Penn Station to the venue, and request an aisle seat for my dad so he could stretch out his leg if he started to have a tremor. I’ve come to recognize that attending theatre with such a relatively simple planning process was a profound privilege. To see Oklahoma! together now, post-stroke, we’d need to think through all of the logistics carefully. Though my dad is still sharp in many ways—he has an acute emotional awareness of himself and others, he keeps up with the news—he no longer has the capacity to play as active a role as he once did in figuring out those logistics. Prompted by my friend’s encouragement, I decided to make the trip happen. I began doing research.

I did a dry run, going to the show on one of the press nights, and I discovered something about the Circle in the Square I hadn’t noticed before: At first glance, it appears there’s no way to get from the ground level to the auditorium without taking an escalator or stairs. Plus, for anyone with mobility issues, going from the house to the restroom seems to be challenging or impossible, since bathrooms are located an additional flight down.

Telecharge, the company that services ticketing for the production, has a dedicated line for its Access Services department. In my first call, a representative looked up wheelchair-accessible seating, which in this case is in the last row, next to the doors. To use the restroom, we would need to ask an usher for assistance. Due to my dad’s condition, I said, he might need to go to the bathroom in the middle of a scene; could we get him to the facilities during the performance if necessary? The representative seemed unprepared for this question, saying simply, “I guess so—as long as it doesn’t disrupt anyone.” Disability can take many different forms, and in my dad’s case one issue is that we don’t know when or if he may to need to go to the bathroom. Bringing my dad to the theatre at all would be difficult, but such customer service responses can be further discouraging for patrons who may not have the ability to sit still or to stay in one place for the entirety of an act.

When I did order the tickets, the process was straightforward: I told the representative we needed a wheelchair seat, they asked how many non-wheelchair attendees would be in the party, and checked whether the wheelchair patron would remain in their own chair. Subsequent interactions with Telecharge didn’t go as well, but purchasing the tickets was not stressful.

The day before our show, Telecharge sent a reminder email with some helpful information, including a prompt to print our e-tickets, as the venue is not yet equipped to scan tickets from a mobile device. (If patrons aren’t reading their emails carefully, though, they might miss this important detail.) That message provided an email address for any customer questions, so I replied looking to confirm details about the process for entering the theatre once we arrived; I had read something about the elevator being outside the theatre proper and wanted to know more about that. Telecharge got back to me in less than a half hour, saying they could better address my question on the phone. So I called, and after eight minutes on hold, they answered my question, saying, “Seating is accessible from the orchestra level,” then noted that an escort to the elevator is available. The representative’s cadence suggested they were reading from a script, and it wasn’t clear why they couldn’t send the same message in an email. I asked about the location of the elevator, and they put me on hold for a few minutes, only to get back on to advise us to come early and speak to an usher.

Due to my dad’s mobility issues, the most convenient way to travel (when we don’t have access to an ambulette) is by car. So the following day, the day of the show, when I learned there were some road closures affecting Midtown, I called Access Services for guidance. They didn’t have information about the closures and had no advice on strategies for getting as close to the theatre as possible. These are reasonable questions, and especially for people who face barriers to attending, should be easier to answer.

The show was at 3 p.m., so my dad’s weekend caregiver and I started getting my dad ready to leave at noon. At 12:45 I requested a rideshare, and the vehicle that came was an SUV, which is trickier for my dad because of the height, but the three of us worked together to get him in his seat and in his seatbelt. At 1 p.m. we were on our way to Manhattan. We still weren’t clear on which roads were closed, so once we got into the city I followed along on the rideshare app; I got a bit nervous when the driver accidentally took a turn that went against what the GPS recommended. But it was a happy mistake: We ended up on 51st Street with unimpeded access to the theatre through the plaza; we wouldn’t have been able to reach 50th Street, the side on which the Circle in the Square is located. The three of us were in the theatre lobby before 2:15.

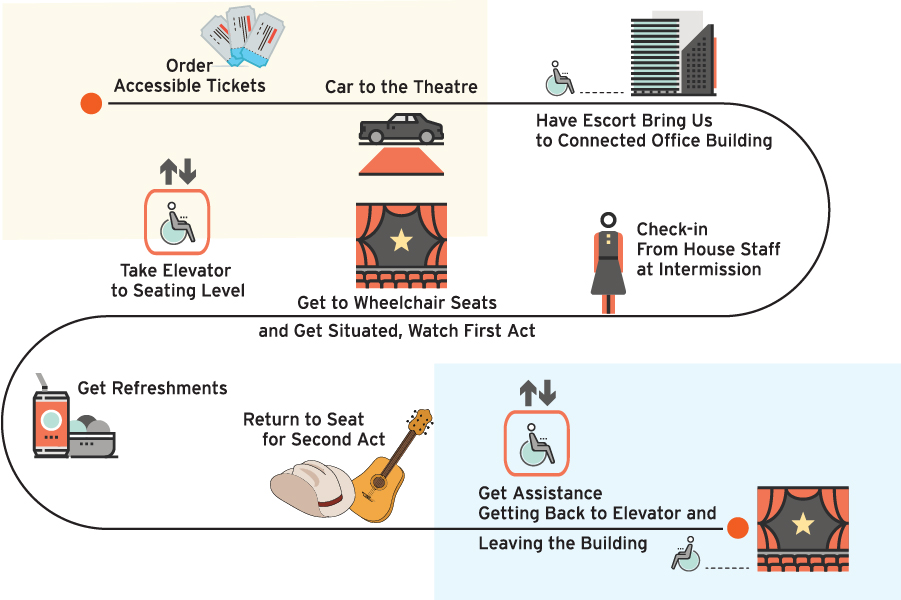

After asking a couple of people where audience members in need of an elevator escort should go, a ticket taker told us to wait near the lobby entrance. Barely five minutes later another staff member greeted us, checked our tickets, took them somewhere for a minute, then returned to look quickly at the bag with my dad’s supplies. That staff member next directed us to go outside and walk along 50th Street to the end of the office building adjacent to the theatre, then wait at that building’s front entrance. When we got there, the staffer was unlocking the hinged glass door next to the revolving door so we could get my dad inside with his wheelchair. They brought us through the turnstiles and to the elevator, then took us to the level with accessible restrooms. At that point, one of the theatre’s porters led us back to the elevator and to the orchestra level.

With more than 20 minutes to curtain, my dad, his caregiver, and I were in our seats with my dad in his spot by the door. My dad is most himself and most at ease when he’s in a new environment he finds exciting or when he meets someone new, and as the show was about to start, the experience met all of these criteria. An usher about my dad’s age chatted with him, saying of this interpretation of the musical, “It’s different, but you’ll enjoy it.”

I had worried my dad might get worked up because of the number of people in theatre, but at the top of the performance, he was enthralled. During the first couple of numbers, my dad sang along, which helped him stay engaged with the performance. A few people turned around to see who was making noise, though their looks of judgment vanished when they saw who it was. While singing aloud at a Broadway musical is usually a faux pas, it would be much less stressful to have the chance to see shows in an environment in which that—going to the bathroom if the need arises, or leaving your seat to get something to drink—would be acceptable. These pages have included a number of discussions of “relaxed” and sensory-friendly performances, though at this point Broadway offers such performances only a handful of times each year, through TDF’s Autism Friendly series, just one per production in a given season. Even with that series, modifications are geared toward the needs of individuals on the autism spectrum, not necessarily creating the type of freedom that would benefit people with conditions like my dad’s. Another notable breakthrough is the advent of Roundabout Theatre Company’s relaxed performances, which consider neurodiversity more broadly, but so far each season includes only a handful—a total of four in 2019, two on Broadway and two Off-Broadway. It would be a great advance to see most or all Broadway productions offer relaxed performances of this kind throughout the year.

Some individuals who’ve been on Parkinson’s medications for a number of years can get fixated on what’s called goal-directed behavior. They can feel an intense need to do something that can be so powerful it may cloud their judgment—some patients on these meds, for instance, become addicted to gambling—or motivates them to the point that they can think of nothing else. In recent years my dad, who had been a big advocate of drinking water, has developed an even deeper love for soft drinks, and as the house lights were blinking to indicate the end of intermission, he asked me to get him one; though it’s often challenging for him to stand up, when I said we should wait because the second act was about to start, he began to stand without assistance, intending to get the drink himself. So I dashed to the bar, purchased the soda, and made it back to my seat before the lights went down.

The rest of the performance went by without incident. Though at times my dad was slightly distracted, the experience went smoothly. When the performance ended, we went back across the orchestra-level lobby, where a member of the theatre’s management staff brought the three of us through those doors to the elevator and up to street level, then led us out of the building and wished us well.

Debates over conduct in the theatre often center around the use of phones, texting, and supposed raucous behavior. For many folks with physical and cognitive challenges, though, the need for different theatregoing standards is not about etiquette but about access. My dad didn’t end up needing to use the restroom during a scene, but it was a possibility. And many people would benefit from a designated performance—whether it’s called “relaxed” or “sensory-friendly” or the like—that allows flexibility for unplanned bathroom trips, singing along, or snacking during the show. I’m new to grappling with these issues myself, but I’ve become acutely aware of how they make attending theatre difficult for many individuals with special needs, particularly Broadway shows in legacy buildings.

Our outing revealed how much room there is for improving the experience for theatregoers with challenges of various kinds, though I will say that the theatre staff was more successful at making us feel welcome than Telecharge. To help me process how things went that day I spoke with a couple of people with an intimate awareness of Parkinson’s, and both expressed a similar wish for making theatre more accessible to people of all abilities. Dr. Rachel Dolhun is the vice president of medical communications for the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and a trained movement disorder specialist (a neurologist with expertise in treating conditions such as PD, dystonia, and Huntington’s disease, among others). Both she and Lucy Roucis, an actor with Parkinson’s and a longtime company member of Denver’s Phamaly Theatre Company for disabled theatre artists, speak to the need for more education of theatre workers on serving disabled patrons. When asked what theatres across the country can do to become more accessible, without hesitation Roucis responds, “They have to make spaces for wheelchairs and companions. They have to make everything wheelchair-accessible, and that includes the stage, because that’s one reason that theatres won’t hire people in wheelchairs.”

“Any community or organization can do a little bit more education of their theatre staff and ushers on people who might need extra assistance,” Dolhun adds, underscoring that while PD is known for its physical symptoms, such as tremoring and stiffness, frequently the condition involves non-motor symptoms such as “cognitive problems or memory and thinking changes.” Just last month the foundation published a guide to cognitive changes related to Parkinson’s. “Sometimes some mood changes like depression or anxiety that can make you not want to go to the theatre or not want to be around crowds,” Dolhun says.

Phamaly often performs at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts, where patrons are routinely asked if they need aisle seats. Roucis recalls leading a training session for ushers in which she tied “their feet together about a foot apart and had them walk.” She asked how it felt and they replied, “Very unsteady,” to which she said, “Well, that’s how a patron could feel walking.” She highlights that she has observed improvements, mentioning that when people see her it’s clear she has a disability and they’re considerate and helpful when they have that realization.

Similarly, Dolhun advocates for greater attentiveness to audience members with challenges. The Circle in the Square staff handily met that bar, thoughtfully checking in with us periodically. I had told my dad about the complimentary chili and cornbread served at intermission, and since getting those items involves going to the stage and waiting in line, picking it up himself wouldn’t have been possible. After the first act I was in the process of figuring out how to get down to stage level when a theatre staffer stopped by to see if we needed anything, and my dad looked up with a smile and asked for chili. The staff member politely agreed and shortly came back with chili and cornbread for us. My dad’s eyes lit up when they brought it.

Dolhun stresses that PD patients and their loved ones should keep doing what gives them pleasure, no matter the challenges. “It is so important for people, whatever they’re experiencing—whether it’s Parkinson’s, dementia or cognitive problems, mood changes, both of which can go along with Parkinson’s—to try as much as possible to continue to do the things that they love and enjoy doing,” she says. “Because Parkinson’s, and being a care partner for somebody with Parkinson’s, can be very lonely and isolating things.” Regarding activities that make people happy, she adds, “Whether it’s doing them in different ways, or differently than you used to do them, it’s so important to incorporate those things that bring you joy and bring you happiness, and exercise your mind a little bit.”

Based on our time at Oklahoma!, I can attest to the benefits of taking that extra effort to continue pursuing activities that create joy. When we got back to my dad’s place, his caregiver’s daughter stopped by to touch base with her mom. When she came inside, my dad looked up from his recliner by the door and said with a grin, “I saw the first Tony winner in a wheelchair. She was magnificent in today’s performance.” During Ali Stroker’s big number, “I Cain’t Say No,” my dad seemed zoned out, looking down more than at the stage, but it later became clear what an effect that song, and Stroker’s performance overall, had on him.

Special experiences like this improve my dad’s physical, emotional, and cognitive well-being, as was the case that day. Commenting on Stroker’s performance he said, “She’s among the superstars in life who are my mentors at overcoming great difficulties and achieving greatness.” If there’s an opportunity for that kind of inspiration, you really can’t say no.

Oklahoma! features music by Richard Rodgers and book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II, based on the play Green Grow the Lilacs by Lynn Riggs; original choreography was by Agnes de Mille. The production is running on Broadway at the Circle in the Square Theatre, directed by Daniel Fish with choreography by John Heginbotham and orchestrations, arrangements, and music supervision by Daniel Kluger. Sets are by Laura Jellinek, costumes by Terese Wadden, lighting by Scott Zielinski, sound by Drew Levy, projections by Joshua Thorson, and special effects by Jeremy Chernick.