One day during rehearsal, director Adrienne Campbell-Holt found herself painting the walls of a set. It was for a world premiere play being mounted by her theatre company, Colt Coeur. It was a 10-person piece called Zürich, with one set, a hotel room, that featured a painted wall and door on one end and a floor-to-ceiling glass wall on the other.

As a director working Off-Off-Broadway, Campbell-Holt is used to multitasking. In addition to directing plays for Colt Coeur, she’s also the artistic director, where she manages operations, writes grants, and “drives the truck, loads the truck—you know, all the things,” she says with a wry smile. Sometimes that means painting the set.

Campbell-Holt is also used to doing more with less. The set she painted looked like it cost at least six figures. When she tells me it only cost $2,400, my jaw drops. “It was slick, right?” she says happily. Maybe I shouldn’t be so surprised. After all, this is Off-Off-Broadway.

How to define Off-Off-Broadway? It’s an amorphous thing. The popular assumption is that is refers to any production in a New York City venue with fewer than 100 seats. But operating under that rubric are a dizzyingly wide range of companies, with annual operating budgets ranging from $50,000 to more than $1 million.

Randi Berry runs the Indie Theatre Fund, which provides grants to Off-Off-Broadway producers (their next granting event is Oct 2). Berry considers Off-Off-Broadway primarily an aesthetic. “It’s not just seats or budget,” she explains. “It’s innovative theatre happening in small, intimate spaces. The work is more diverse, the work is more risk-taking. That’s where the research and development for the whole American theatre takes place, in indie theatre. It’s more collaborative—there’s also sometimes a different hierarchy in the structure and ensemble. Technically it’s 99 seats or less, but to me it’s all of those things.”

Indeed other monikers also frequently applied to Off-Off-Broadway theatre are “indie,” “downtown,” or “experimental,” meaning outside of the mainstream and sometimes weird as hell. Off-Off-Broadway is where you go to see a play in someone’s actual basement, or actors frolicking in goo, or an immersive experience that takes you all around Lower Manhattan, or a show that turns into a literal sleepover.

Off-Off-Broadway’s birth can be traced to 1958 at a Manhattan coffee house called Caffe Cino, where gay artists were given a platform (a 10-by-10-foot stage, to be exact) to tell their stories in a time when it was illegal to do so. From those humble beginnings, many of today’s most innovative theatre artists made their careers, and honed their aesthetic, Off-Off-Broadway: Wooster Group’s Elizabeth LeCompte, Richard Foreman, Basil Twist, Suzan-Lori Parks, Taylor Mac, Young Jean Lee, Dave Malloy, Reggie Watts, Alex Timbers, and Rachel Chavkin, among countless others. Many of the city’s brand-name theatres remain Off-Off-Broadway: La MaMa, HERE, Performance Space 122. Work from Off-Off-Broadway has even found its way uptown to Broadway: Harvey Fierstein’s Torch Song Trilogy got its first staging at La MaMa, and Heidi Schreck’s What the Constitution Means to Me premiered at the 89-seat Wild Project in the East Village (and produced by the Off-Off-Broadway company Clubbed Thumb).

Off-Off-Broadway is the anything-goes playground of theatre artists, the place where they make their professional debuts, where they can let their creative freak flags fly. It’s not a launchpad to Broadway, or even Off-Broadway; it is its own ecosystem. Off-Off-Broadway is where theatre artists go to redefine what theatre can be.

That’s not to say it’s a utopian, art-first landscape; the price for total and complete artistic freedom is that almost nobody makes a living wage, let alone a living, doing it. “If they do, they either have personal money or they have a partner who can support them and allow them to do the work,” says Virginia P. Louloudes, executive director of ART/New York, a service organization that provides grants and low-cost space rentals to NYC’s theatre companies.

But measured in terms of output and vibrancy, Off-Off-Broadway is thriving, sprawling, and diverse. It stretches from the Bronx to Brooklyn, and comprises artists from all backgrounds. The Innovative Theatre Awards, which recognize indie productions, estimates that around 2,000 Off-Off-Broadway productions open every year, everything from one-night one-offs to months-long runs. And despite a funding landscape that prioritizes bigger companies over smaller ones, these artists are making it work—they’re finding what money they can, stretching it, and in some cases using it to grow. Here’s how they’re doing it, and why.

In 2007, a group of 20-something actors who all graduated from New York University met at a Starbucks and decided to form a theatre company. They were all performers of color; seeing a lack of opportunity in the industry for folks who looked like them, they decided to create their own. They called their new troupe the Movement Theatre Company. “At the time there wasn’t a home for young artists of color to work,” says Movement co-founder David Mendizábal. “A lot of the POC theatres were dormant and larger theatres were not welcoming. We wanted to create a space for artists of color to collaborate with each other.”

Their first production fell into their lap. The French Embassy was looking for a company to produce Bintou, a French play by Koffi Kwahulé, about an African girl defying her parents’ rules. The Embassy could provide $10,000. Movement volunteered. Mendizábal directed a cast of 16. Everyone was working at night and for stipends. But the energy was so electric, he recalls, that it propelled Movement to keep producing. “I always say the original sin was forming a theatre company,” says Mendizábal with a chuckle. “If we knew what that actually meant, we probably would not have.”

Movement Theatre is still going strong; their most recent production, of Aleshea Harris’s What to Send Up When It Goes Down, was extended three times last fall (and will get an encore staging next month in Washington, D.C.). Their current operating budget is $130,000. But none of the four members of its leadership team are full-time. For Mendizábal, the long-term goal is to produce more regularly (Movement has produced six full-length shows since its founding) and to build infrastructure, including finding funding for one full-time staff member and office space. “I would love us to have some kind of office and rehearsal space that isn’t my living room, and some storage that isn’t all of our apartments,” he remarks.

Movement’s slow growth mirrors the struggles of many Off-Off-Broadway efforts. If you’re a small theatre company self-producing shows for under $50,000, and you want to grow even a little bit, let alone a lot, where do you start?

For one, it takes a few stages. Most small producers start out mounting productions under the showcase code with Actors’ Equity Association, which allows its members to work without benefit of contract. As such it only allows for 16 performances; payment is not required (though many pay at least the cost of a MetroCard), and a showcase doesn’t count as work weeks toward health insurance. So what happens when you have a runaway hit and want to extend past those initial 16 performances?

That was the dilemma that faced the Mad Ones in 2010, when they were mounting their first production, Samuel & Alasdair: A Personal History of the Robot War, a devised work about an alternate reality where robots invade the planet. Initially produced for $4,500, it sold out its initial run at Brooklyn’s Brick Theatre, then had a hit encore run in Manhattan at the New Ohio Theatre. As the Mad Ones weighed extending that run, they faced a dilemma: It would mean paying themselves the official Equity contract rate, as well as $3,000 upfront to AEA (a bond in case a production is cancelled or postponed, so that actors are guaranteed a week’s pay). And per AEA rules, once you go up a contract level, as a company you can’t go back down in the future.

“We got together as a group and asked, ‘Do we want to do it, will we recoup the money? What if we extend and people stop coming?,” recalls Mad Ones co-artistic director Joe Curnutte, who performed in Samuel & Alasdair.

Adds co-artistic director Marc Bovino: “The difference between showcase and the code right above it is so exponentially high that it’s really cost-prohibitive in a lot of situations. We had to just put down cash to say, I’m going to gamble on it.”

The gamble paid off. The extension sold out, the play won an Innovative Theatre Award, and its members are now respected artists in the field (including Obie-winning director Lila Neugebauer). The Mad Ones are still going strong today, though they still have no full-time members or staff; when they do come together to stage a show, they co-produce with larger Off-Broadway entities who do most of the heavy lifting, like Ars Nova or the Signature Theatre, where they’re in residence. “We couldn’t have done the things we’ve done and continue to do without a co-producer along the way,” says Bovino. “That’s been our strategy: Never do it alone. If we had to rent a theatre, the cost would be so prohibitive that we would never have done a show.”

Many artists who spoke for this story agreed that from a funding perspective, hovering in the $50,000 to $250,000 budget range can put theatres in a kind of no man’s land. When you’re a small theatre company just starting out at the bottom end of that range, you might qualify for grants geared toward “emerging” talent. And if you near or cross the $250,000, you might be eligible for more and bigger grants, including ones from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Finding a way to level up is the challenge Campbell-Holt is facing with Colt Coeur, whose operating budget is currently $140,000 and whose season includes two full productions. In its nine years of existence, Colt Coeur has amassed an impressive production history: it premiered Dry Land by Ruby Rae Spiegel, its production of Fish Eye starred Betty Gilpin. But its operational growth has fallen behind its artistic ambitions. “We’ve outgrown the grants that are for companies that are new and have $50,000 to $100,000 budgets,” Campbell-Holt explains. “But a lot of the foundations and grants that we’d like to apply for, you need $250,000 or over $500,000 operating budgets.”

The urge to grow isn’t just about better production values; it’s also about paying artists more for their work. Contrary to popular assumption, Off-Off-Broadway artists aren’t entirely happy working for free. “I think 95 percent of our budget goes towards artists, and I’m really proud of that,” says Campbell-Holt, who is herself still not full-time at Colt Coeur.

The company is currently on a three-year agreement with Equity, in which they plan to pay actors and stage managers more each year until year four, when they will graduate to an Off-Broadway contract (which starts at $615 a week). As a freelance director herself, with a new baby at home, Campbell-Holt knows that for artists to stay in the field they have to be paid well. She wants to do her part to help.

“It’s extremely important to me that theatre is not a space for privileged people to work who can afford to not make a living wage,” says Campbell-Holt. “Especially for parents who work, if childcare costs more than the fee, that’s not tenable and that needs to change.” After talking to me on a break from rehearsal for Colt Coeur’s fall production, Eureka Day, she gets up to go pump breast milk.

The Bushwick Starr in Brooklyn can testify that once you reach the quarter-million-dollar budget threshold, producing becomes much easier. Founded in 2007 when a group of friends decided to turn their apartment into a performance space; by 2014 their operating budget was $325,000, and it has swelled to more than a million since. They still perform out of that same apartment, but no one lives in it now (unless it’s part of a show).

“I do remember feeling we broke through to something more sustainable in terms of institutional giving when we started to get multi-year funding contracts,” recalls co-founder Sue Kessler. “This is what happens at many institutions: Funders will notice your budget is growing so they’ll reflect that in the giving.” And because funders look at the last three years of a company’s budget, consistency is key. Kessler admits the Starr did have some help early on in the funding department: Actor Keanu Reeves happened to come a show and was so impressed that he became a board member.

Despite its relative stability, larger budget, and seven full-time staffers, the Starr still operates on the showcase code and what they call “mini contracts” with Equity, which are more generous than showcase but less than Off-Broadway. That’s what enables the company to continue producing ambitious, large-scale work in a 70-seat house while keeping ticket prices under $30 and making rent (no easy feat in a gentrified neighborhood like Bushwick). They also co-produce all of their works: On 2016’s Miles for Mary, the Mad Ones provided $30,000 and Starr provided $15,000, plus operating and marketing support. When the show extended, the Starr paid for the additional labor costs. The next step for the Starr: to fully produce an entire season.

To co-founder Noel Allain, growth has been crucial to the Starr’s longevity. “There’s only so long an organization can function in a healthy way when people are working past the number of hours they’re getting paid for, or not getting paid,” he explains. “You need to build that infrastructure. You need a healthy, functioning staff of people who are getting compensated, and give their full attention and don’t get burned out too fast.”

Adds Kessler, “Even through all that growth, we strived to maintain our mission and our character—being a place that is still supporting new and exciting work without commercial pressures. That’s hard to do.”

Here’s a statement of fact, not an opinion: Producing theatre was much easier in the 1970s and ’80s. That was because, according to ART/New York’s Virginia Louloudes, you could get some city and state funding “that covered everything—overhead, staff, actors. You only needed to raise money for your production.” She should know; she’s been working in arts administration since 1978. But these days, with high cost of living and high rent in NYC, young artists looking to self-produce or start their own company are facing a new set of challenges: a decrease in foundation and government support, combined with ever-rising costs of space rental (now usually the biggest line item in a production budget).

And there are more small theatre companies now competing for those scarce funds and spaces than ever. Off-Broadway and Off-Off-Broadway producers pay a membership fee to access ART/New York’s resources, and its membership has doubled since the ’90s, with the largest increase being in companies with budgets below $100,000. Today that budget level makes up 54 percent of ART/New York’s membership. But even as more small companies vie for a shrinking funding pie, the majority of remaining grants continue to go to theatre companies with budgets over $5 million. That leaves small companies with few pathways to grow.

“I think the way you look at a healthy ecosystem is: Are they able to go from embryo, to nine months, to birth, to year one, to year five?” says Louloudes. “Right now I’ve got a lot of embryos! They’re healthy but they want to grow up. You want to keep that churn going, so there can be new embryos coming in when they graduate from NYU or Yale School of Drama.”

This is why Randi Berry formed the Indie Theatre Fund, an organization where member companies contribute five cents per ticket sold during a production; the money is then regranted to other small theatre companies. Berry is also currently close to signing a lease on a space she wants to rent out to artists for a low rate. What she worries about is indie theatre becoming solely a young person’s game, as older artists leave the city because they are priced out.

“The rising cost of real estate makes it very difficult for people to continue here,” she says. What happens when older theatremakers leave the field is “we lose institutional knowledge. Older theatremakers, they can’t sustain it, they can’t create family here, because of real estate cost and also their cost of living. It shortens the amount of time people are staying here and making theatre. People can’t maintain a foothold unless they own a space.”

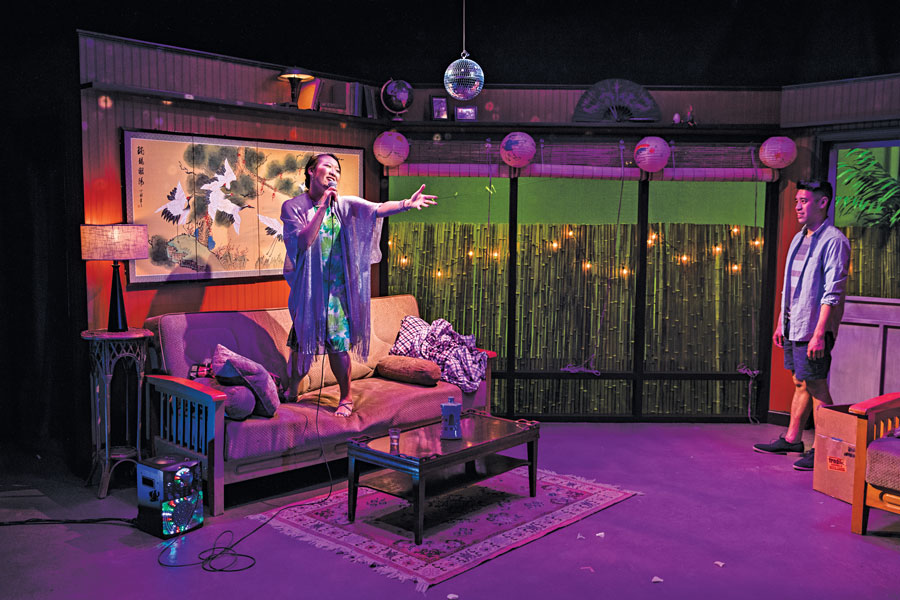

That problem is exacerbated for companies that serve marginalized groups, including people of color. This is a source of frustration for Chongren Fan, who runs the $70,000-budget Yangtze Rep, which focuses on producing work through a Chinese diasporic lens. Fan finds that funders who give out grants for diverse programming have mid-six-figure budget requirements. But because most companies focused on marginalized communities tend to be lower-budget, these minimums become another way marginalized artists are excluded.

“These days, all the foundations and all the big grant givers, everyone is requiring companies to have diverse programs, and so suddenly all the predominantly white institutions, because they’re already operating on a higher budget, all they need to do is change a little bit of their programming to include, like, one Asian play or one African American play, and suddenly they get more grants,” Fan says, visibly frustrated. “The funders aren’t giving us money!”

The way to close this gap, as Fan sees it, is multipronged: Funders could create a requirement that larger companies need to work with smaller companies to be eligible for funding, or those large companies could reach out to indie theatres of color to co-produce. “It’s better to co-produce with a company that has been doing a similar kind of work and also bring them up, rather than saying, ‘I only need to take your artists,’” he says. “It’s a larger conversation this country is having right now: How to bring people up? It’s not just money, it’s also platforms and opportunities.”

Even with all its challenges and inequities, many artists on the Off-Off-Broadway scene who spoke for this story remain optimistic that as long as there are artists living in NYC—if they can afford to—there will be artists who want to make theatre in it. Off-Off-Broadway artists’ concerns aren’t that different from their Off-Broadway, Broadway, and regional counterparts: creating work within a budget, attracting audiences, compensating artists fairly, raising money. And as much as regional theatres look to co-productions and collaborations, New York companies facing rising rent and cost-of-living are joining forces: Off-Broadway companies like Playwrights Horizons, New York Theatre Workshop, and the Signature have begun to co-produce work with Off-Off Broadway companies. Indie theatre companies are also pooling resources: Yangtze’s next show, Salesman之死: The (Almost!) True Story of the 1983 Production of Death of a Salesman at the Beijing People’s Arts Theatre Directed by Mr. Arthur Miller Himself From a Script Translated By Mr. Ying Ruocheng Who Also Played Willy Loman, will be co-produced with Gung Ho Projects and presented at Target Margin Theater’s new space in Brooklyn.

Berry would like to see a more systematic approach. “My goal for other members of the theatre community, Off-Broadway and Broadway, is to recognize the contribution of small theatre in their work, and for them to give a nickel per ticket,” she says forcefully. “If Broadway had done that last year, it would have given us $650,000. Most of the people who are on their stage and working backstage started on a small theatre on 4th Street, they started in a basement in Bushwick. Theatre is a circle, not a ladder. There’s a lot of people in indie theatre who intend to stay there, and they still add value.”

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story misspelled Caffe Cino’s first name as Cafe. An earlier version also incorrectly named Gregory Diaz IV as George Diaz IV.