In a recent weeknight in downtown Columbus, Ga., I was up late laughing with friends over pints of craft beer. This was a unique situation for me, as a mom with two young kids and a full-time-plus job. I was attending a one-off improv class hosted by Muddy Water Theatre Project, a brand-new pop-up theatre company founded by local artists Austin Sargent and Ben Redding. Truth be told, I needed more than one pint to get through some of the games; my heart pounded like it did during the improv classes I took at the local Springer Theatre Academy as a kid. But as I looked around at the 15 or so other adults—men and women ranging in age from 20s to early 50s—I was thrilled by what I saw.

Here in this mid-sized city in the Deep South, a place I swore I would leave after high school and never return, I was living a version of life I never thought possible. An event like this would have been nonexistent in the early 2000s, when I graduated high school. The craft beer wasn’t there, and neither were city blocks of trendy restaurants and bars in the downtown area. The only active theatre in town then was the Springer Opera House, a historic venue founded in 1871 with an annual budget of $2.5 million and audience of 112,500. There were no plucky new theatre projects run by some pseudo-prodigal children, determined to infuse more inclusive, diverse, and innovative theatre programming into the city’s cultural fabric.

But now there are.

When people think of Georgia theatre, Atlanta generally comes to mind. But just a couple of hours south in the midsize city of Columbus (population: 197,485), a small, independent theatre community is growing, run by younger artists (average age: 35), and catering to a diverse audience. If you want something for the kids, there’s Family Theatre or Springer Children’s Theatre. If you’re looking to be inspired by smart, powerful young adult artists, check out a performance by the Fountain City Slam. For a late-night, anything-goes cabaret, grab a beer and a chair at No Shame Theatre. And if you’d rather watch a play in the park, a speakeasy, or a 200-year-old Greek revival-style home, nab tickets to a Muddy Water production.

The indie scene’s growth has been relatively organic, fueled by artists who love their town and didn’t want to live anywhere else, or those who, like me, left and came back for a better (and more affordable) lifestyle.

In 2013, my husband and I had been married for a year and were living in Boston. He was studying law and I was writing and developing plays with Company One, when I wasn’t working my admin day job. Then our daughter was born and my husband graduated from law school. Saddled with educational debt and under-employment, we needed to regroup somewhere other than one of the most expensive cities in the country. My parents convinced us to move back to Columbus, where the cost of living was low and grandparents would be nearby to help with the new baby.

Within a few months of moving back, I became depressed. My sense of a future as a playwright was grim. I had studied and lived in New York, where opportunities for developing and producing my plays felt innumerable. Boston had nurtured me and given me a sense of value in its theatre community. I considered Atlanta my only hope, but with traffic it was nearly two hours up the highway. I felt daunted and ill-equipped to crack the nut of the Atlanta theatre scene.

Then something occurred to me. I had been writing plays about Columbus for years. Surely my work would have an audience here at home? Meetings with the Springer Opera House initially failed; producing artistic director Paul Pierce was understandably apprehensive about the financial risk of producing a new play by an essentially unknown writer; the Springer seasons generally feature well-known plays.

So I decided to self-produce. Word of mouth, emails, and coffee dates revealed a somewhat subterranean community of thea-tremakers in Columbus. By day they were pastors, students, admins, teachers, and servers. But when they clocked out, they were eager for a community-theatre gig—even a non-paying one. A month later, in August 2014, I offered a free staged reading of my play The Old Ship of Zion at the Synovus Bank in Downtown Columbus. I received financial support for space and refreshments from Artbeat, a nonprofit that presents an annual two-week-long arts festival in the spring.

At that reading we had a captive audience of more than 100 witnessing a play about a Black, queer, Christian college student trying to find his way at his beloved, centuries-old Columbus church. When the talkback lasted an hour and some audience members tearfully talked about how much they related to the protagonist’s journey, I knew Columbus was ready for new plays. My depression began to clear.

Columbus prides itself on being a city with a philanthropic heart for the arts. I found that to be true when producing The Old Ship of Zion. The budget for the production was about $6,000, nearly all of it raised by local donors. The space was comped by the National Civil War Naval Museum. Each of the 20 individuals who worked on the production received a stipend ranging from $100 to $500. Because of the success of the box office, everyone got a $100 bonus after we closed.

Five years later, I consider my production of The Old Ship of Zion the most meaningful thing I have done in my career. I have produced once more since—an immersive, tour-like event in 2017 featuring six short plays by six local playwrights in six rooms of a historic home in downtown Columbus. This was again funded by local donors and an Artbeat grant. It was free to the public and filled to capacity by young, diverse patrons as well as “traditional” theatregoers. At productions and events like this, we are helping the community rethink what thea-tre looks like and who is qualified to create it. And we’re not the only ones.

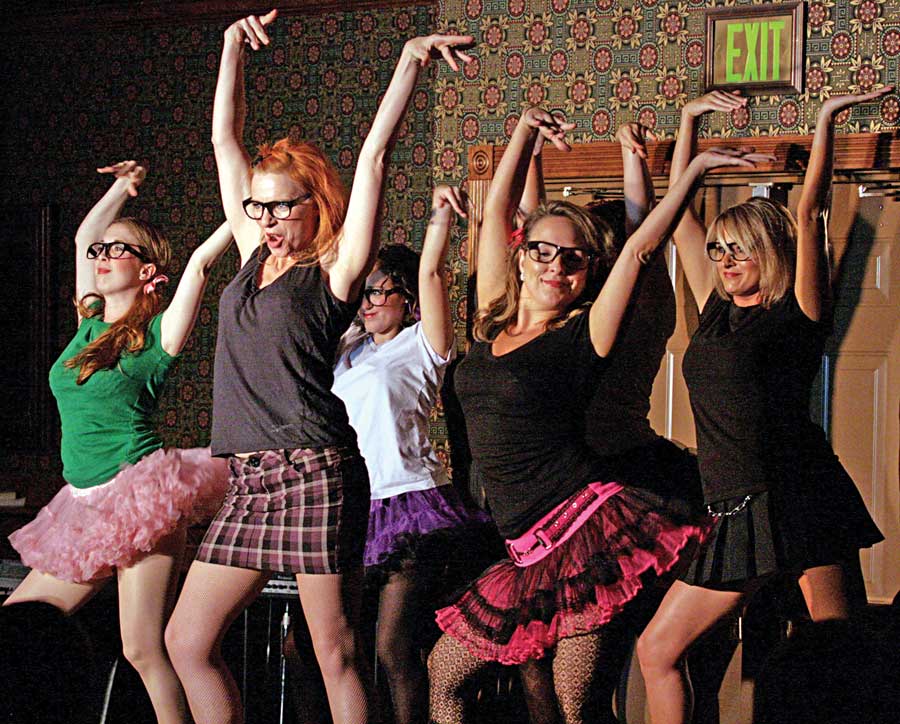

(Photo by Sonnet Moore)

Muddy Water Theatre Project has no roof. Its projects materialize in green space, museums, historic homes, bars, or, as was the case with the improv class, coffee shops. While some of these spaces have been donated, many receive a kickback from Muddy Water ticket sales or bar tabs. This helps to keep budgets low and creative possibilities high. Still, funding remains a challenge.

“What we’re being offered now is time and talent,” says cofounder Sargent. “There are people who live in this town who have more money than they know what to do with but are slow to spend it. And then there are people who want nothing but to help and don’t have the financial ability to donate.” In-kind donations, including the donation of labor to build sets or source props, have proven crucial as Muddy Water kicks off its first season.

Thankfully, Sargent and Redding can learn from the example of local couple JJ and Kate Musgrove, director of donor services at the Community Foundation and retired chair of Columbus State University’s theatre department, respectively. Shortly after relocating from Virginia in 2003, the Musgroves established a nonprofit theatre company they called Chattahoochee Theatre Ensemble. They put on children’s shows and musicals, but soon found there was some toe-stepping going on with other companies. “Everybody had their own turf, and you didn’t cross-pollinate, so to speak,” JJ Musgrove remarks delicately.

In 2008, Chattahoochee Theatre Ensemble transformed into Sherlock’s Mystery Dinner Theatre, in part to carve out a niche market on the scene. The Musgroves co-write each script, multiple characters are played by two actors, and the audience is called on to participate around 12 times a night. The couple have been successful over the past decade; their two productions a season bring in anywhere from $1,500 to $3,000 each, which is enough to put back into the company to produce the next one.

Each actor is paid about $100 per performance, so over the course of a production they’ll earn around $1,000 each, not including their rehearsal stipend. Staff and other artists involved are also paid per production. This is a step beyond community theatre.

JJ Musgrove explained that much of their success is owed to strong marketing (billboards, radio spots, social media). The funding for that comes from an annual grant from the Columbus Cultural Arts Alliance, which is never more than $20,000. The grant must be applied for every year; Sherlock’s has been fortunate to receive funding whenever they apply.

Musgrove recalls speaking with Sargent and Redding when they were preparing to launch Muddy Water, in the interest of forming a theatre community. “We have an opportunity here to work with a lot of people who want to do things well, and who also want to cross-pollinate,” he says. Indeed, nearly every grassroots theatre effort draws from individuals that work at and/or with other arts institutions. Tribalism is now nearly non-existent.

An actor from the cast of Old Ship of Zion, Jonathan S. E. Perkins, singlehandedly runs the Fountain City Slam poetry workshop. Perkins knows how to cross-pollinate. He has produced and performed on multiple stages in Columbus, taught at the Springer Theatre Academy, and worked at the Liberty Theatre Cultural Center, a historic landmark originally opened in 1925, and the area’s first African American theatre. Perkins says the advantage of being a theatre artist in a city like Columbus is that it is easy to find a platform and get to work. Like me, he moved back to Columbus, in his case in 2004. “I saw opportunity,” he remarks. “There was enough going on, enough interest and access, that I just walked into town and started stage-managing, directing, producing.”

But access like that can be challenging when you aren’t a hometown kid like Perkins or myself. Actor and producer Amanda Rae says she had trouble when she moved to Columbus from Seattle in 2018. “It was hard to find people who were collaborating,” she says. “I was spending a lot of time online trying to find people.” So she created a Facebook group, and after a few months it became a very active digital gathering space. Currently there are nearly 200 individuals in the #ColGAThtr group, and it buzzes with audition notices, show announcements, monthly happy hour invites, and occasional random requests, such as, “Is anyone here an ordained minister?”

This has given Rae the kind of perspective and access she needed to find her niche. “Here I’m leaning less into traditional thea-tre and more into interactive events that make people go wow,” she says. “There’s a lot of opportunity to connect to all kinds of people.”

Perhaps because we are comfortably situated in the Bible Belt, many artists in Columbus want to make art not only for themselves but for the community. One area in which Columbus’ theatre community shines is the way it serves the under-served.

Sally Baker, director of education at the Springer Opera House, returned to her hometown of Columbus in 2015. “When I came back to Columbus, I saw what a divide there was in our city,” she said. “Not only a racial divide, but a socioeconomic divide. So I’ve been working hard to work against that and disrupt assumptions about that.”

One of Baker’s attempts to bridge that divide was her creation of the PAIR program (Professional Arts Integration Resource). PAIR sends teaching artists to public schools, many of which are Title I, to collaborate with teachers on arts-integrated curriculum for students. In the few years PAIR has been at work in Columbus, students involved have had notable academic and behavioral growth.

Beth Reeves, education coordinator for the Springer, has found arts integration work particularly transformative in her classrooms at New Horizons, a behavioral health center. A Black teacher in a room of majority Black boys, she seeks to connect with her students in creative ways. “They’d come in some days fighting, literally fist fighting,” she explains. “I would walk to the middle of the room, start telling a story—they’d stop. I have to be a griot to them.”

Another griot in our community was the late Tamara Curry-Gill, who moved to Columbus from Los Angeles in 2013. A talented Black actress and director, Curry-Gill invested a lot of early energy directing and producing a Shakespeare in the Park rendition of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The production came together, but it wasn’t easy. I know she felt frustrated at times navigating the personalities, pace, and scope of the project, especially as a new transplant to the city.

As she let go of trying to make Columbus into a version of L.A., Curry-Gill found her calling as drama director at G.W. Carver High School, a predominantly Black high school in East Columbus. Her students found that drama wasn’t just for white kids or rich kids. They were introduced to the canon of August Wilson, the state Thespian Conference, and the August Wilson Monologue Competition.

In February 2019, Curry-Gill and her students presented an original Black History Month performance entitled “Power,” meant to uplift and celebrate the Black experience. When they closed the show, Curry-Gill’s Facebook status read: “Winding down from a wonderful production of POWER! My students were amazing and most importantly they enjoyed themselves.” Three days later, she would die of a heart attack; she was only 45 years old. At Curry-Gill’s funeral, one of her drama students stood at the altar with a notably pregnant belly and performed Vera’s monologue from Seven Guitars. The weeping stopped, and everyone simply held their breath to witness the power of live thea-tre in its most earnest form. This month the auditorium will be renamed in her honor.

Columbus has the tendency to be self-congratulatory (our city slogan is “We Do Amazing”). But the wary among us are not allowing that maxim to make us complacent. Though many artists here work on a smaller scale, they have ambitions to grow. Whether or not the city can help facilitate that is another question.

In the past, smaller companies have closed due to burnout and under-funding, or beacuse bigger and more attractive cities lured their founders away. The Columbus Cultural Arts Alliance is the only major annual funding source for Columbus arts orgs. And while individual donors can be generous, in a city our size the biggest givers are well known by all of the major nonprofits. A fledgling company must fight hard to compete for support—all the more challenging while its members toil at full-time day jobs.

Troy Heard, artistic director of the critically acclaimed Majestic Rep in downtown Las Vegas, was a homegrown Columbus director who founded the experimental Chattahoochee Shakespeare Company in 2007. ChattShakes put up bawdy, explosive comedies and compelling dramas in bars, old mill villages, and downtown traffic medians. Despite an enthusiastic following, Heard grew weary of the many civic hurdles around using non-traditional spaces.

“And when I did have space such as the historic and beautiful Liberty Theatre, Northern Columbus audiences were reluctant to come to that part of town,” Heard recalls. The decision to move west in 2009 felt like the obligatory next step for him, and it has proved to be a successful one. Back in Columbus, many are pressing on through similar obstacles.

But I’m optimistic. When I consider what has grown here in the past five years, I’m certain that this mid-sized Southern city is witnessing a new era of independent thea-tre. The energy is palpable and the community is beginning to respond in major ways with physical and digital engagement, and yes, dollars. Commissions of work from independent theatre artists by existing organizations are becoming common. Most importantly, we are collaborative and mission-connected creators, more focused on working together to broaden and deepen the theatre scene than outdoing one another. Like the Chattahoochee River after a strong storm, we are rising—together.

Natalia Temesgen teaches creative writing at Columbus State University.