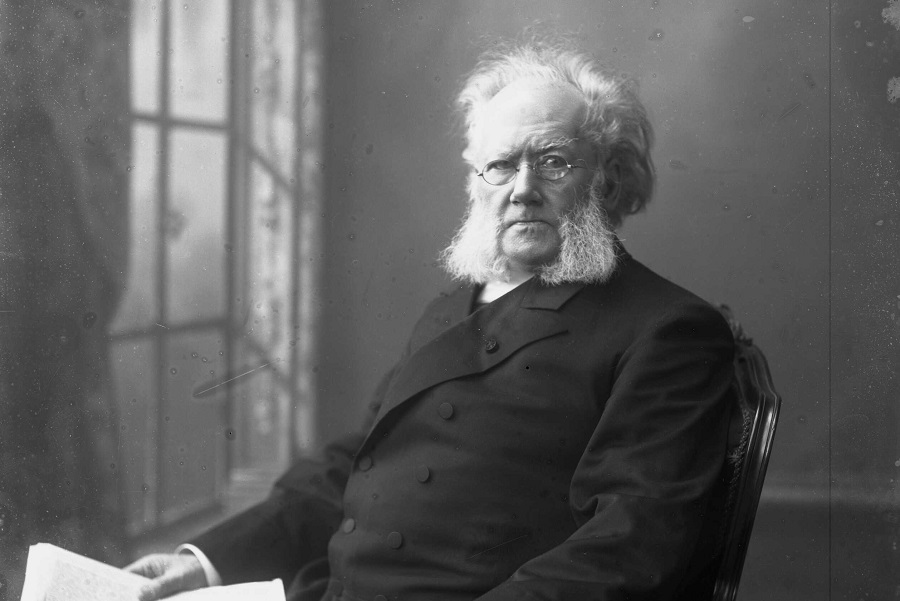

How do we understand Henrik Ibsen? Theatrically, he was the Master Builder himself, setting the pattern and standard for more than a century of contemporary drama. Playwrights since Aeschylus have used the theatre to ask social questions, but Ibsen was the one who perfected the delivery system for bourgeois audiences—the ones, for better or worse, who became the theatre’s backbone. Ibsen’s recipe involves a mix of middle-class family crisis and a widely applicable moral dialectic; the schadenfreude and melodrama of the first element sweetens the virtue and difficulty of the second. That structure has worked in one way or another for nearly every realistic playwright you can name since.

When Ibsen started writing, Norway—then the lesser partner in a union with Sweden—was enough of a cultural backwater that there weren’t even many plays written in Norwegian; serious writers wrote in Danish, until Norwegian nationalism made language an urgent issue. Ibsen rose from obscurity—he was a failed student, a penniless poet, a debt-saddled chemist’s apprentice—and dominated five generations of drama, not only in Norway but in Europe, the U.S., and beyond. How? Is there some way to understand him well enough that we can understand that?

I can now say confidently: No. Ivo de Figueiredo’s biography Henrik Ibsen: The Man and the Mask gives as complete an account as English-speaking readers are likely to ever see. And yet page by page, Ibsen seems smaller. The connection between such a man to such a body of work seems more opaque than ever.

As de Figueiredo looks deep into his subject, it turns out that the extraordinary writer was a rather irritating personality: jealous and petty, priggish and peacocking, adolescent and hypocritical. The one thing he had in abundance was overweening self-confidence. “My book is poetry; and if it is not, then it will become so. The idea of what poetry is…will submit to my book,” he writes when a critic complains about his Peer Gynt. The braggadocio would be unbearable—but for the fact that he turned out to be right.

The nearly 650-page book is actually an abridged version of de Figueiredo’s two-volume biography, published in Norwegian in 2006 (Henrik Ibsen: The Man) and 2007 (Henrik Ibsen: The Mask). In combining the two books, the author condensed both text and notes, excising, as he says “almost all references to primary sources—letters, diaries, etc.,” while retaining references to other scholars. Even in its shortened form (the other volumes are not available in English), de Figueiredo’s outline of Ibsen’s life is breathtakingly complete.

To give you a sense of its exhaustiveness: In 1869, the playwright goes to Paris for two weeks, and de Figueiredo doesn’t know exactly what he does there. This tiny silence (two weeks out of 78 years!) is such an exception to the general storm of thickly documented incident that the biographer draws attention to it. He seems almost embarrassed at the lacuna, and tries to ferret out what might have happened regardless. What might Ibsen have seen? How might a few nights at the French theatre have changed him? De Figueiredo is forced to guess. But for the rest of Ibsen’s life, the scrupulous de Figueiredo can shadow his steps almost footfall by footfall.

Throughout, and perhaps because of this granular detail, the biographer is cautious about making sweeping statements he can’t root in research. Where others have made claims that linked the playwright’s biography to his motivations, de Figueiredo instead issues historical contextualizations. For example, it has been tempting over the years to see the bankruptcies in Ibsen’s plots in relation to his own father’s fall from fortune, but de Figueiredo assures us that in those early days of bourgeois wealth-building, a tumble wouldn’t have been particularly embarrassing. The same goes for Ibsen’s oft-mentioned out-of-wedlock child, whom he was legally forced to partly support. De Figueiredo indicates that far from feeling singled out about the child (whom he never saw), Ibsen was one of many such fathers, repudiating the moral claim and dodging the bill collectors whenever he could.

In the body of the book itself (or at least this condensed version), de Figueiredo largely doesn’t mention the scholars he is correcting or corroborating, which means it is less useful as a reference text than it might otherwise be—you’ll need to head to the notes to puzzle out what or whom he means by “posterity,” for example. More importantly, the loss for the English-speaking reader of the other (untranslated) volumes’ endnotes about primary-source materials saps this book’s value for the reader who wants to understand the welter of information. For the non-academic, of course, such an encyclopedic element may seem unnecessary, but it’s frustrating to encounter something that’s both completist and partial at once.

The translation by Robert Ferguson is graceful, though the book itself can have a somewhat gluey forward movement. It is certainly good and careful scholarship, and it draws the reader’s attention to the peril of using biography to make overly broad claims. But in such a long book about a tedious man, it’s a bit dangerous to remind us quite so often that Ibsen’s life may not illuminate his strategies on the page.

So, the life. As a child, Ibsen liked to play with puppets—a hint of the future. He was a “bright, irritable character” who, once he left his family to make a living, rarely got in touch again. (He and his sister did write affectionately, but he let his father die, years later, uncontacted and in poverty.) By the early 1840s he was working as an apothecary’s apprentice—this is when he fathered his out-of-wedlock child—and then, in the late ’40s, he went to the capital city of Christiania (the earlier name for Oslo) to try to enter university.

His mind was consumed with becoming a writer, an ambition that seemed to be bound up with a capital-R Romantic sense of spiritual overreach. His earliest serious poem cries out with purple self-regard:

Is the flash from soul’s dense darkness,

Breaking through the murk forlorn,

Flaring forth with lightning starkness,

Merely for oblivion born?

In his collegiate days, Ibsen was surrounded by the young academics and rebels of Christiania, themselves kindled by nationalist and democratic dreams. Ibsen’s writing found a place in magazines published by these friends, and his reputation began to grow—though his one play, Catiline, was rejected for production. Meanwhile his debts, including a mounting pile of unpaid child-support payments, loomed. Ibsen was on the verge of being sent into forced labor when Ole Bull, a superstar violinist and passionate advocate for a new Norwegian-language theatre, cherry-picked him to direct and produce. Ibsen sailed for Bergen with debt collectors at his metaphorical heels, untried as a theatre manager, but desperate enough to try.

In Bergen, Ibsen’s shortcomings as a director would eventually swamp him, though valuable travel opportunities and continued work in the theatre honed his playwriting skills. He eventually returned to Christiania to be the creative director at the brand-new Norwegian national theatre, Kristiania Norske Theater, where he was able to mount his own plays The Vikings at Helgeland and Lady Inger of Østråt.

Though not runaway successes, the plays’ reception marked a vital aesthetic break with the past. In the 19th century, critics judged artistic quality on elements like “beauty” and “reconciliation.” If Ibsen’s early plays were lugubrious, they did at least manage to push through those stifling old criteria. Even though he had not yet written any of the works we remember him for, Ibsen had already formed his theatrical creed—discernible, for instance, in his introduction to a published version of Catiline. “For Ibsen the most important feature of dramatic structure…is the divide between its exterior and its deeper interior structure,” de Figueiredo writes. “Dramatic conflict is something that arises in the interplay between the drama’s deepest ideas and its surface.”

By the end of the 1850s, Ibsen was in crippling debt again. Political and cultural debates around Scandinavianism and Norwegian nationalism couldn’t make his writing or work at the theatre a paying concern, and he was somehow unable to manage the hodgepodge of other jobs that could have kept him, his wife Suzannah, and their son alive. (As he does throughout the book, here de Figueiredo contrasts Ibsen with his friend and rival, the other great Norwegian theatre figure from the period, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson.) Ibsen fled debt again, this time heading for Rome. “The axe had fallen,” de Figueiredo writes, “but the prisoner had escaped.”

For the next 27 years, Ibsen was in almost perpetual “exile” from Norway—a self-imposed absence that was equal parts practical and pouty. Even after money was no longer a concern, even though royalties were often hard to collect in Germany and Italy, he kept himself away out of a deeply felt pique. He had been so unappreciated! And the writing was certainly easier overseas. He did, though, happily draw an annual writer’s wage from the government. He railed against Norway for its failures, but he also made sure to constantly apply for an increase in his subsidy.

Abroad, Ibsen wrote the verse drama Brand, which thrilled people with its call to an uncompromised life, and the folklore-filled Peer Gynt. At age 47, he made a huge aesthetic shift with The Pillars of Society, a riot-starting international hit that made him a succès-de-scandale. In Society, he discovered his mature style, and he now began writing the bourgeois dramas (A Doll’s House, etc.) that made him an international titan. The way critics hated him became part of his legend. They called Ghosts “an open drain” for its frank (and medically inaccurate) discussion of syphilis, which only spurred his sales.

De Figueiredo hastens to tell us that Ibsen—somehow always under the banner of revolution but never quite holding it—was not suddenly turning into a naturalist, let alone a part of the “radical littérature engagée.” The biographer exposes again and again how deeply this seemingly “revolutionary” author was politically incoherent. Indeed, he was an aristocratic exceptionalist through and through: He hated the masses and was often mocked by his peers for the way he grubbed after honors and medals. Ibsen loved authority, both his own and anyone else’s, especially if they had a throne.

Your idealized vision of Ibsen may have already been pulverized by such revelations, but the book keeps grinding over those bones. For instance, you might think of him as a feminist. Will you lose faith when you see how old Ibsen treated hero-worshipping girls, pawing at them against their will, stealing kisses, and assuring them, “I need youth…for my writing”? Or will it be when he—back in Norway at last—sulked through a dinner in his honor because they have seated him next to a woman in her 40s?

Ibsen’s behavior wasn’t just entitled and abrupt. It was notably beyond the pale. He thrust people away from him; he repudiated or ignored family members; he reacted to favors with the anxiety of a man who had a deep fear of ties. It’s interesting that the artist who most articulated the creed of individualism was psychologically incapable of anything other than an isolated life. “One might wonder how it was that a man so divorced from ordinary social life nevertheless managed to capture his time as well as he did,” notes de Figueiredo. He eventually concludes that “the work may be greater than the writer,” and many of his readers will have doodled this same thought in the margins some 600 pages previous.

So. We are lucky to have this book. It is sweeping, complete, careful. It is valuable to have the delusion of the “great man” washed away; it is always useful to hear how often “individualism” is actually just the sound of selfishness justifying itself. Also, it could not have been written by a better thinker: De Figueiredo’s distillations of the dramas and their structures are always welcome and sometimes superb—there’s one passage in which he links Ibsen’s artistic journey to Kierkegaardian phases of development that’s as elegant as an ostrich feather.

On the other hand, I have had periods of wishing I had not read it. Henrik Ibsen: The Man and the Mask is a long, long time to spend in sour company. Ibsen was a pill, and being shut up in a book with him for a week was a difficult experience. Nora slammed that Doll’s House door, and I’m sure it was satisfying. The last time I closed this book, I gave it a little bang myself.

Helen Shaw is a New York City-based critic and arts reporter.