Daniel Fish's reimagined version of Rodgers & Hammerstein's Oklahoma! recently won the Tony Award for Best Musical Revival. Below, in an excerpt from Volume 3 of Musical Theatre Today, Daniel Kluger (who was nominated for the best orchestration Tony) discusses his process for reducing the score from its original 28-piece full orchestra version to one that can be played by a seven-piece band, including a banjo, a pedal steel, and electric guitar.

Composer, producer, and sound designer Daniel Kluger was tapped to re-orchestrate Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! for a contemporary string band, in a production that moved from Bard SummerScape to St. Ann’s Warehouse to Circle in the Square Theatre on Broadway. In this conversation we discuss the DNA of songs, musical intimacy, spreadsheets, Logic Pro, and the ever-present question of “Why?”

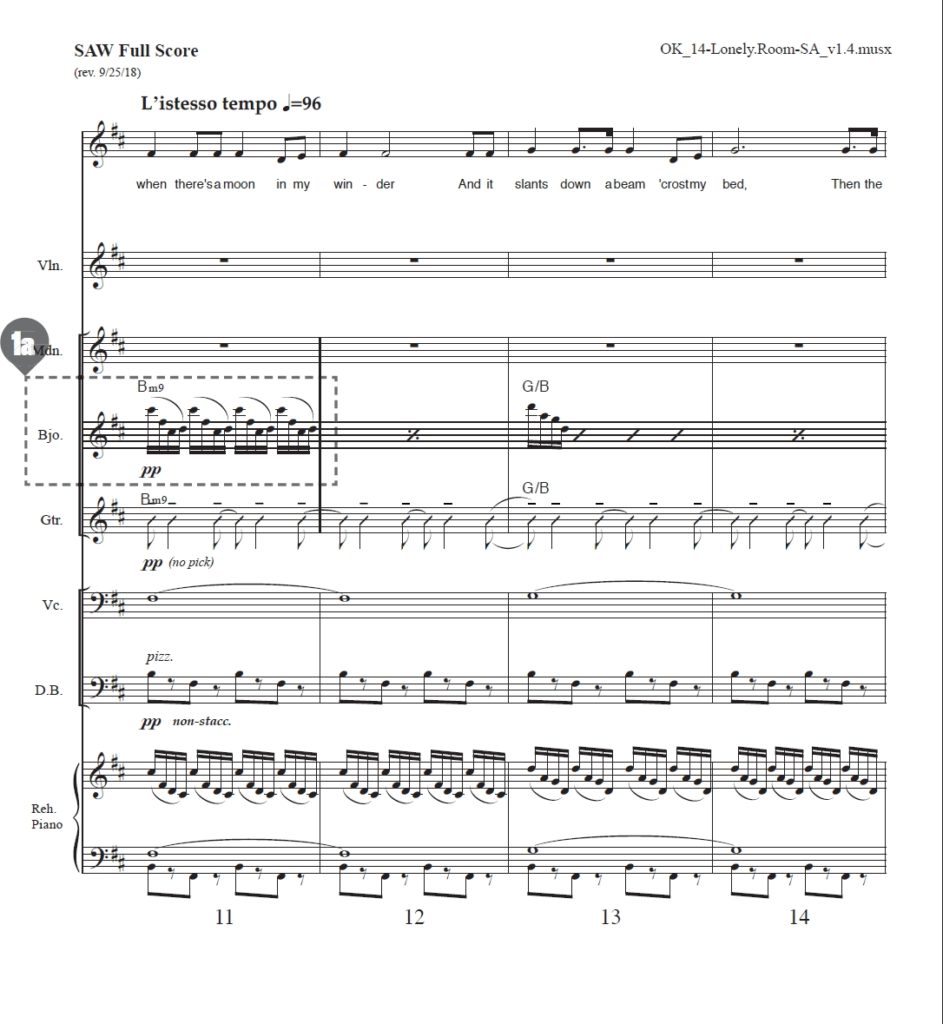

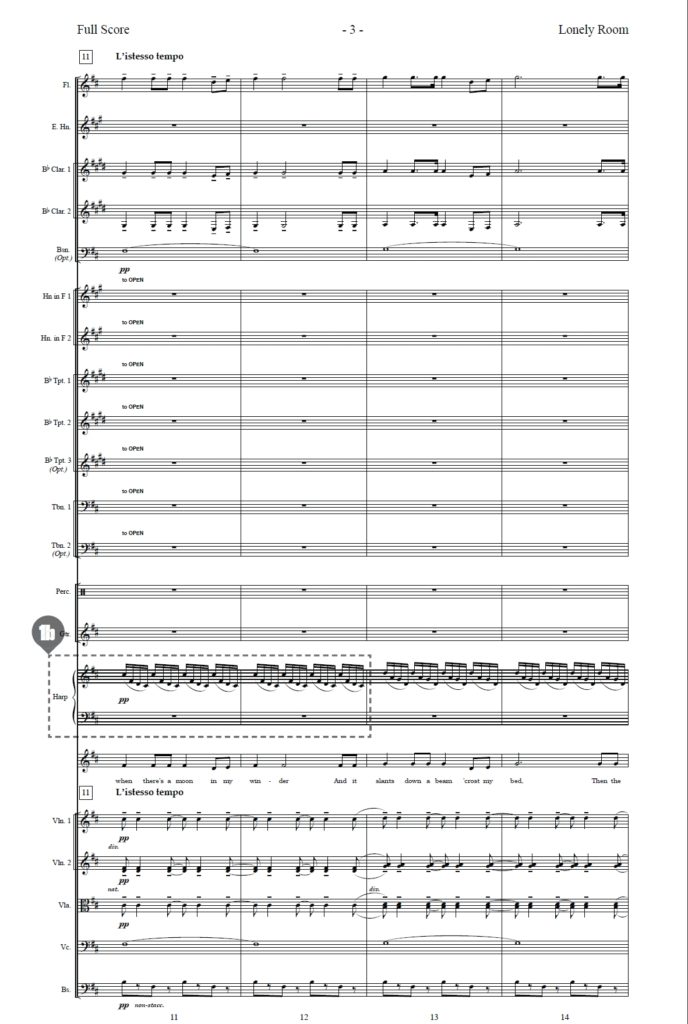

MUSICAL THEATER TODAY: These running sixteenths in “Lonely Room”: those were originally played by the harp, right?

DANIEL KLUGER: Yeah, harp. This one’s kind of simple in hindsight… This is basically how I worked; I would copy and paste things down [from the original orchestration]. It just occurred to me that [in the St. Ann’s Warehouse production] this is a rare example of doubling the melody on violin. You know, it’s common to double the melody line in the orchestra, but often we didn’t have enough voices. When we did it the first time, we had no cello.

So you opted to not double the melody very often.

Most of the time we would not, because we were prioritizing other things; and I think not doubling the melody makes it feel more contemporary, you know? A rock band never doubles the melody. That’s a kind of theatre-y thing that was easy to remove right from the beginning.

When you take the whole process, what were some unexpected discoveries? Were there things that you shifted based on the players’ response, or based on the sitzprobe?

Definitely. I mean, it took so long and it’s all kind of a blur…. How can I tell you this in a way that’s interesting? We ended up doing a lot more re-voicing of string parts in the final pass at St. Ann’s. We started from the beginning wanting to be as faithful as possible to the architecture of the original. In melody, harmony, dramatic intent… And the Robert Russell Bennett orchestration has a lot of [material that] we’ve come to think of as part of the song itself. In other words, the countermelodies and some of the—

[hums the descending instrumental countermelody from “People Will Say We’re In Love”]

Exactly! That is part of the DNA of the song. If you look at Richard Rodgers’ original piano score—which is a cool thing to check out sometime—some of that’s there and some of it’s not. So it made sense at the beginning to think of reducing that orchestration rather than making a new one for this band. And there was a lot of, “I don’t know how this line is gonna work, so I’m just gonna copy it down and we’ll see how it goes.” It was a bit of trial and error, but a lot of times it was magical, like the first time you hear that [harp figure] on banjo [in “Lonely Room”] (although, that’s actually not that big of a stretch)….

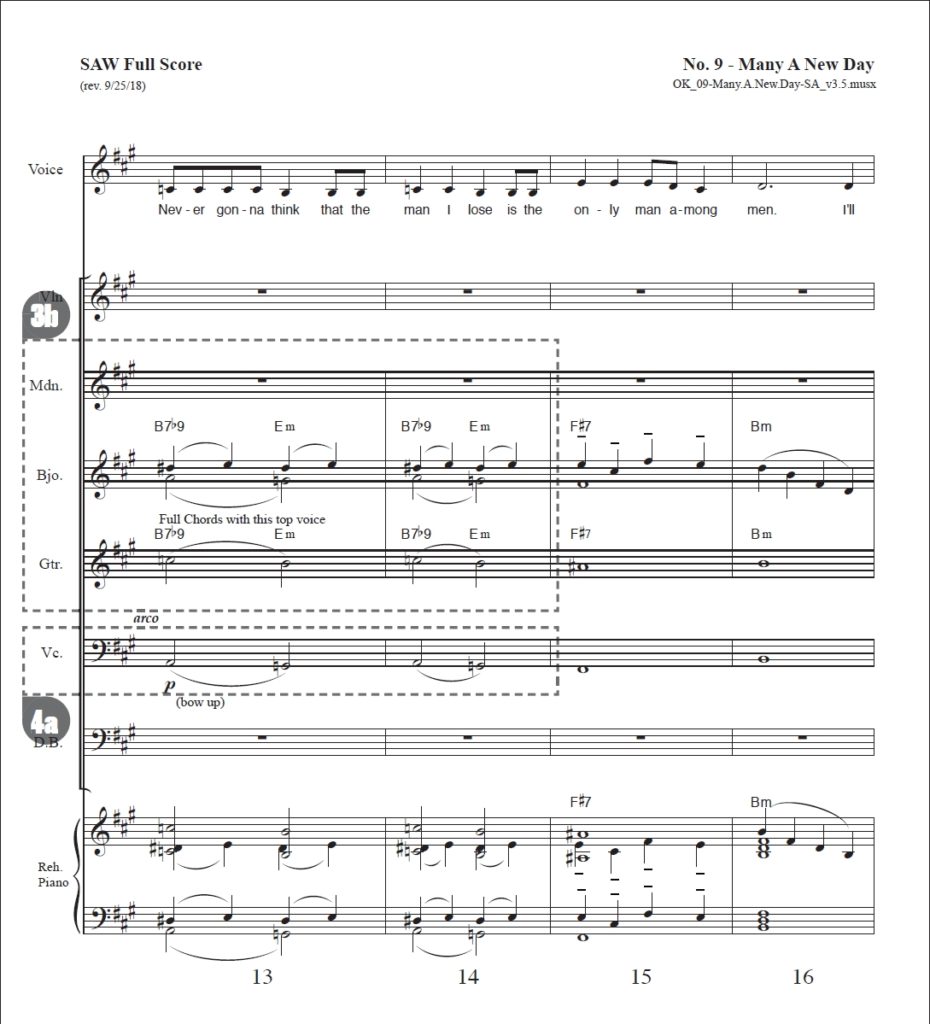

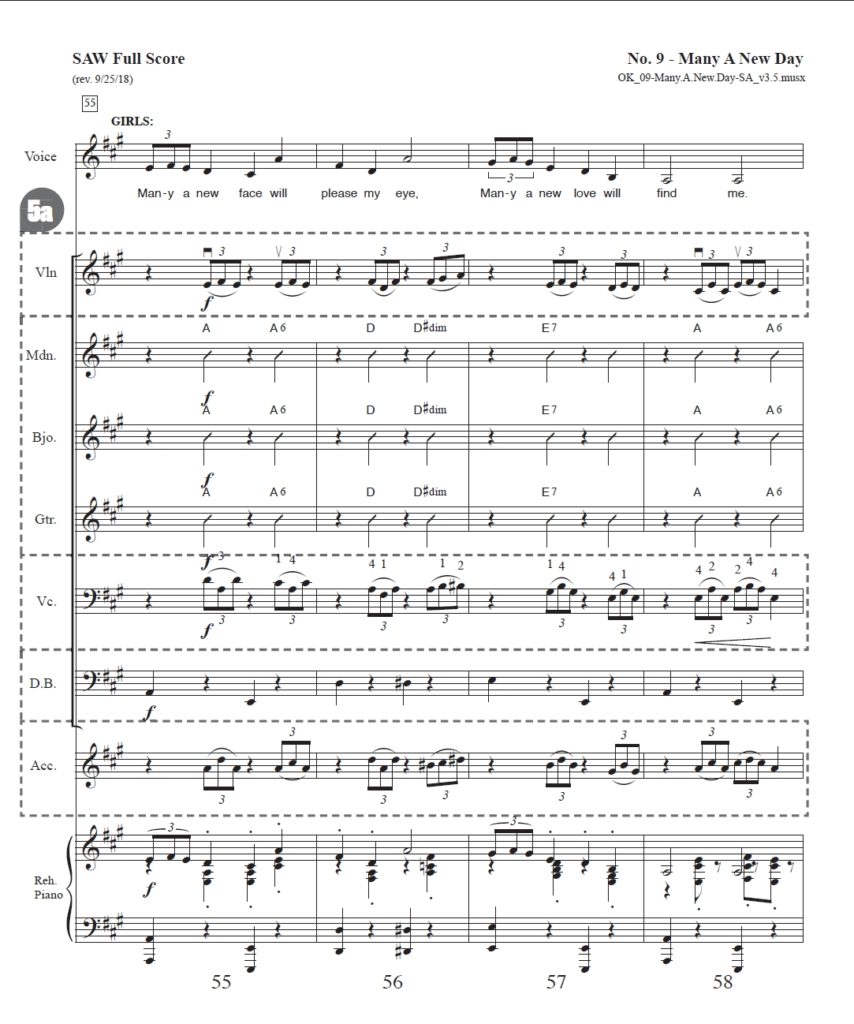

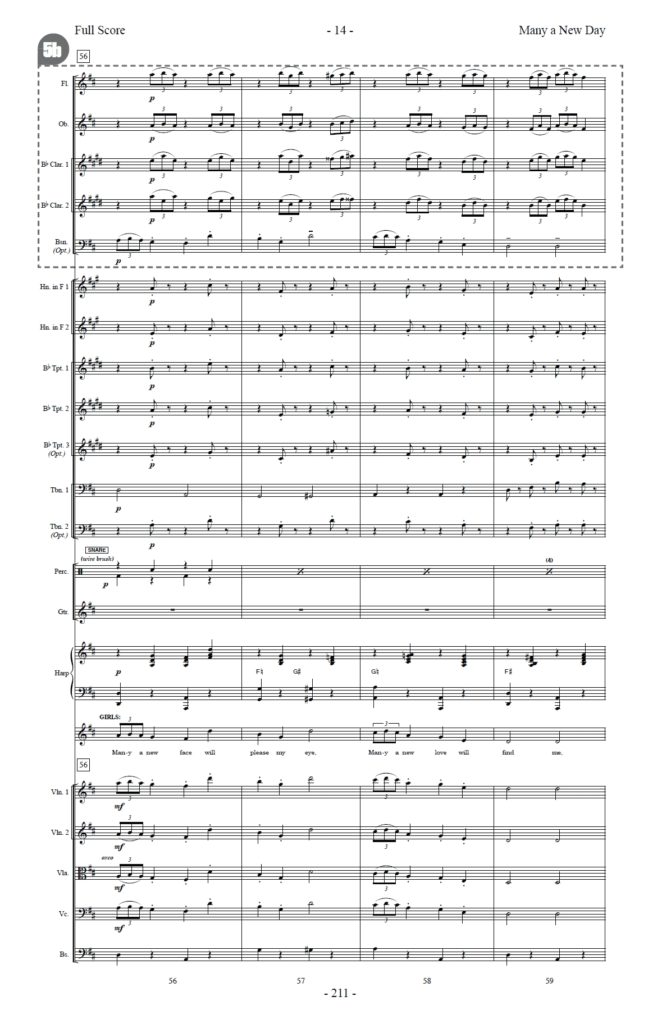

What’s a good example? Let’s take something that has lyrical countermelodies: “Many A New Day.” Sometimes I’d take something that was a wind line, something lyrical and legato, and put it on a solo plucked instrument, and it would just come to life because it was more fragile and exposed. And the same principle applied to the harmonies. “We’re going to make a guitar part that’s totally faithful to the harmony. We’re not going to simplify it for a guitar player at all.” This is a really great example: [sings] “That’s one thing you’ll never hear me say / Never gonna think that the man I lose is the only man among men.” Let’s look at bars 13 and 14… flute and oboe, horns… so this is really kind of lush… I would distill it, but make sure every voice is covered, keeping the counterpoint and the voicing as straightforward as possible. That grouping—mandolin, banjo, guitar—often could do a three-voice thing, plucked in a choral style. Oftentimes there’s interplay between a trio of bowed strings and the trio of plucked strings, in conversation with each other. Anyway, I’d end up bringing everything down [from the original orchestration] and then shaping the song, subtractively.

Gotcha.

So, “Let’s build this up from almost nothing; I want it to feel really intimate at the beginning, and then add one instrument at a time.” So here the banjo can take those two lines, and the guitar player can play these chords…

And the cello takes the trombone line.

So that’ll make it a little bit more lyrical, but it’s gonna be soft and the banjo has that nice sort of weird spookiness to it… And then later we get double-stops in the cello, so it gets broader. You’re trying to always have the shape of the orchestration dramatically do what the [original] orchestra was doing—to translate one scale to another. The first time we did the production we didn’t have a cellist, and fortunately we were able to add it for St. Ann’s. The nice thing about the band is it’s inherently intimate, and adding the cello allowed us to cover some of the lushness and dynamic range that the show calls for.

Oh, this is kind of fun. So Nathan [Koci, the music director] plays the accordion—he’ll play the thumb tune there, he’s harmonizing with that—and then here, this was a wind trio… I mean, the original is awesome, but we’re doing that on violin, cello, and accordion, and it has this sort of goofy Euro-cafe feel to it, you know what I mean? [laughing]

The musical gesture at the end, after “Many a red sun will set”—the orchestra has a pretty big comment there, I’m sure that was really broad, maybe it was tutti or something.

And you brought it down to just banjo.

At one point we had all plucked strings playing tremolo, and then eventually—dramatically—it was feeling a little bit much…. People talk about the show being “stripped down,” like, “Oh, it’s minimal: it’s visually minimal, it’s musically minimal,” and on some level I think that’s missing the point, because it’s not so much about removing things. We were willing to question why every piece is there. So that figure in measure 116 was feeling a little too big, so we ended up giving it to the banjo as a solo, in this awesome, green light cue. That’s how something like that ends up that small; it’s really specific to the production.

Were there other places where that happened?

Pretty frequently. We had at one point considered doing “The Surrey with the Fringe on the Top” with only the bass. Voice and bass. You know, he’s sexy, he can hold this moment seducing her; we don’t need to dress it up with ornaments. But really, the interplay between the melody and counter-melody are part of the DNA of the song and we can’t just cut it. So we had to work really hard to ft these ideas into the dynamic of the moment.

It seems like the question of “Why?” was always present.

Yeah, that’s right. We had to re-justify all the ingredients as we gave them to our band. Because our production is in the round, and the musicians are also exposed and right in front of you, it all needed to be properly calibrated in space. If the actor’s over here to your right and suddenly you get distracted by the mandolin doing something over there on your left, that’s not good. So we ended up pianissimo here but it ended up coming together in a really shimmery way—they’re barely playing, but it’s pretty cool.

I remember, it was stunning. Totally magical, and also vulnerable. It’s not a bravado moment, it’s like, “Don’t blow it.” I mean yes, he’s sexy, but we know there’s a lot at stake.

I would say that what makes it sexy…. The dynamic shift and the light cue achieves an intimacy where he says, “I’m gonna get close to you” and she goes with it, and that’s sexy because she accepts the proposal of intimacy.

I love the goal of “intimacy” in the orchestrations and the goal of “honesty,” that it’s always going to be an underscoring for the emotional connections and reactions…. I mean, there are some band-focused moments which are really nice!

And certainly characters have their own bravado when it’s appropriate.

When did you start orchestrating things in your career?

Well, this is the first complete show I’ve orchestrated, so I’m very fortunate to have an opportunity where the music is this good and the director is this good, the players are this good…. And it’s a reduction, so it was a really good gateway experience. But I’ve always orchestrated my own music.

That totally counts.

Although it’s different because when you’re writing your own

music, you can think in orchestration.

And when writing your own music, do you usually think in terms of the instrumental ensemble?

Well, most of what I do is scoring—underscoring and incidental music. So the way I’ve been brought up to think about orchestration is: what production values can I achieve well? “What are the resources to make this sound as good as it possibly can in the room that we’re in?” I’ve always worked out of a sequencer first, and actually Oklahoma! is the first time I haven’t done that. Typically, I’m working in a demo first, because I have to put it up against picture or what’s going on onstage instantly.

What program to you use?

I use Logic. And I would have demo-ed Oklahoma! but at the time there weren’t really good enough virtual instruments of our band that I had access to.… And because I was working with the original “Finale” scores from the Rodgers & Hammerstein Estate, and because we had this great band already lined up, I knew I wouldn’t have trouble putting something in front of them and getting a good result. But it can be really difficult to not have a good demo when you’re working with a director. Typically I write themes on piano and then orchestrate a demo in Logic. And it’s so easy to try different orchestration ideas in Logic. The sequencer inspires you.

How did you approach the Dream Ballet, in collaboration with the director and in the context of this production? I think of everything in the show that was the biggest departure [from the original score] and featured the most contemporary interpretation—

Sonically.

I only absorbed it once, so I wonder what was buried in there that I missed. How did you approach it, and what was the evolution of that?

First we did the arrangement, so we watched the film, and that arrangement is a little different from the version that we got from the estate (which I believe was most recently arranged for the London production). So we were starting with two different sequences of themes. We basically had to take it apart and put it back together, so we rearranged the whole thing. I made a spreadsheet, which is one of my favorite things to do: [pulling up the Google document] “Dream Ballet Master Structure.” I basically took every phrase and said, “It’s up for grabs whether we do it, where we do it, and what key it’s in. But some of the transitions in the material we’ve been given are not broken, so let’s try not to fix them.” Like there’s this nice transitional re-arrangement of the “Surrey” theme made into this chorale. That [instrumental] writing is really awesome.

How did you decide when to use electric guitar versus acoustic guitar?

In the Bard production, Curly played electric guitar live. That’s how it started, and it was more about having him physically onstage. So it started with a bunch of fog and him playing live; a rock thing.

Like a Jimi Hendrix moment—

And then that was superseded in New York with the idea that it would be really awesome if Laurey were onstage, completely alone, without the musicians. There was nowhere to play offstage, so we recorded it, and the studio process opened up other sonic possibilities.

For the Dream Ballet, what turned out better than you expected? You said you were really pleased with it.

The production and mixing—I added 2 synth parts on the Kansas City movement that I’m super proud of….

Again, going back to the honesty in this orchestration, this feels more like a dream. It is like the audience comes back from intermission and then goes, “What? What did I just…”

That’s [Director] Daniel Fish.

Because otherwise, it would just sound like the second half of an orchestra concert; and the Dream Ballet is very pleasant and very nice, but this really does do for an audience now what was probably very shocking and weird then.

Yeah, it’s the music, but also he knows how to make you have an experience in the theater. Every production I’ve done with him makes you feel like that… I’m also really proud of this: we took “Out of My Dreams” and played it on pedal steel [guitar], and then I did a string orchestration behind it. But then Daniel Fish said, “That’s too beautiful. We’re all gonna check out. We can’t do that… We could play just the string part with no melody and drop boots in front of people.”

So then we just played the string parts alone.

Oh my God.

So that’s how that happened.

That is an incredible moment.

It’s weird, right? You have no idea what’s going on, there’s no melody.

The boots are the melody. [Laughter] It is unsettling.

I wonder if you can tell what the theme is at the time. Like if you really know the song, maybe you can follow the harmonic progression.

I mean, it sounds like Rodgers; those slip-sliding harmonies…. My last question for you is: What are your orchestrational/musical influences, inspirations, heroes?

Well of course, Robert Russell Bennett. Stravinsky. Bernard Hermann. Thom Yorke. Brian Eno. Chris Thile of course. He was proof for me that you can do whatever you want harmonically in bluegrass…