Batter up! Roundabout Theatre Company would like everyone to meet Toni Stone, the woefully unfamous woman who was the first female to play big-league professional baseball.

Toni Stone, by Lydia R. Diamond, was inspired by Martha Ackmann’s book Curveball: The Remarkable Story of Toni Stone, one of the few accounts of Stone and her career. “I devoured the book and was shocked and dismayed that I didn’t know Toni Stone,” says Pam MacKinnon, the show’s director. (Toni Stone’s producer, Samantha Barrie*, had recommended the read.) “I felt that it was such an amazing history of the Jim Crow South and of baseball as the American pastime—and of the segregated, parallel worlds of baseball,” says MacKinnon.

Curveball outlines the player’s journey to the Negro League and her hard-won spot as second baseman for the Indianapolis Clowns. White women had been playing professional ball as part of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League since the early 1940s. But as there was no equivalent all-female league for Black players, Stone was relegated to play on an all-male Negro League team.

Stone’s story of overcoming adversity in a man’s field, literally, seemed fit for the stage. And so MacKinnon began to draft players for the project. The first was Lydia R. Diamond (Stick Fly, Smart People).

In the play, Toni Stone (portrayed with vigor by April Matthis) tells her own story. She rattles off baseball statistics, explains the rules of the game, and guides the audience from the practice field to the dugout, all through her childhood memories and defining career points. The memory play is reflective of Stone’s roving mind.

“The structure, and who Toni is, are intrinsically bound,” explains Diamond. Adds MacKinnon: “It’s tantamount to a movie or a novel; it is very fluid. I look at this story as in some respects being an exploration of this singular person’s brain—a very ambitious person who knew who she was. And baseball is at the core of everything she does.”

The play is framed within an extended metaphor. Stone describes her need to play ball as “the weight and the reach”—her hand feels empty without the weight of a red-laced ball. The reach refers to both the act of catching the ball and blazing a trail for women on the baseball field. That metaphor could also be applied to the play’s development process. It was an arduous team effort to tell this woman’s story—to mine the history, to bring a baseball team to life onstage, and to introduce a largely unknown figure to audiences.

“I had to really do a deep dive into all things baseball,” concedes Diamond, who came on board the project five years ago. She had not heard of Stone prior to reading the book, and though she played Little League as a girl, she wasn’t extremely well versed in baseball. The creative team received support from Ackmann and the staff of the Negro League Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Mo., in bringing the story to the stage, and Diamond looked to films such as The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings to learn more about the Negro League. During rehearsals, the Roundabout cast visited Citi Field to get pointers from the Mets, and Matthis dedicates her Mondays to batting practice at Chelsea Piers.

Readings and movement workshops with the Radcliffe Institute, Arena Stage, Chicago Dramatists, and Roundabout all aided in the show’s development over the past few years. “This is how I write a play,” says Diamond. “Especially one like this that has so many moving pieces and so many different voices to get it right. It is such an engine and each gear has to work. And that takes a lot of fine tuning.”

The show’s design elements also help to tell the story. “I feel that sometimes Black American stories on the stage get designed to look like they are set 100 years ago, or the 1890s,” says MacKinnon. “But this was in the 1950s; this is recent history.”

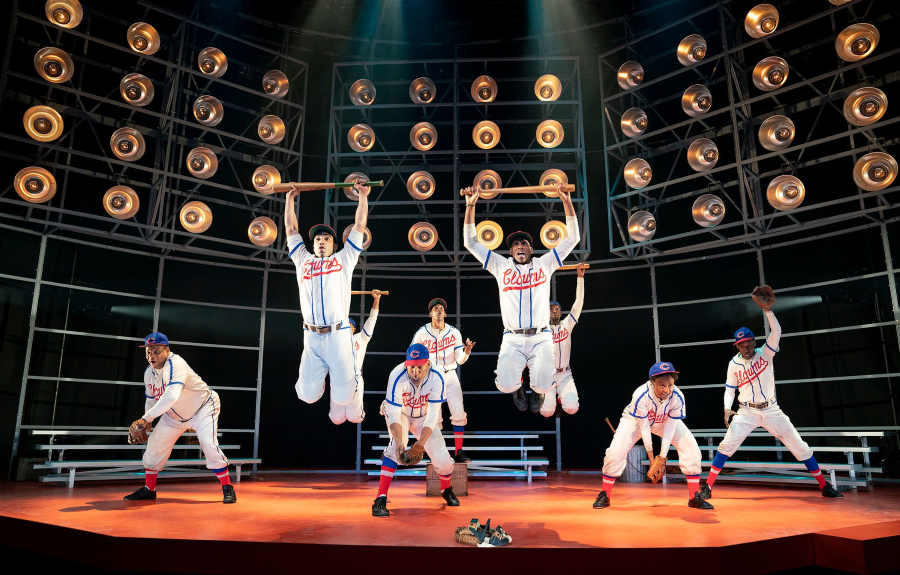

The Laura Pels Theatre is a bit like a stadium, with metal handles lining the aisles and a fan-shaped house. Set designer Riccardo Hernandez capitalized on these features and honed in on the ’50s setting with wooden and aluminum benches onstage, and bright orange colors. “It’s a nod to pop,” describes MacKinnon. “Baseball card Americana pop.” Allen Lee Hughes’s lighting design includes night lights that flash to punctuate dialogue; they’re also a piece of history, as the Negro League used night lights 55 years before the Major Leagues.

Another historical aspect of the Negro League is brought forth by choreographer Camille A. Brown’s movement. In addition to playing ball, many of the Negro League teams, particularly those with “clown” in their names, would perform bits between innings that had elements of minstrel acts. From juggling to dancing the Charleston, it was a tradition of the league. “There was always this sort of performative aspect as well as this athletic prowess,” explains Diamond. “I find that fascinating and complicated and such a part of our American story—and I wanted to look at it in an unflinching way.”

Despite the story’s acknowledgment of America’s disgraceful history on race, the play has elements of lightness. “I think that theatre should always have some laughs; we don’t go to just bleed,” says Diamond. “Theatre is most effective—and particularly political theatre—when we laugh. There is a tradition of laughter in African American culture. Sometimes you have to laugh to get through it,” she says.

“This is a play that could be about oppression, but all these players actually were doing what they loved—playing baseball,” says MacKinnon. “So it’s about pulling out these moments of unbridled joy.”

Some away games are already scheduled for Toni Stone: The play will bow at Washington, D.C.’s Arena Stage April 23-May 31, 2020, and at San Francisco’s American Conservatory Theater, where MacKinnon is artistic director, next season.

“It’s so hard in the American theatre to get a second production,” says Diamond. “So I’m very blessed to be able to have this happen. I want audiences to have met her and to be inspired. It is nice to have been able to introduce her to people who didn’t otherwise know her.”

*Samantha Barrie’s name was misspelled in a previous version of this piece.