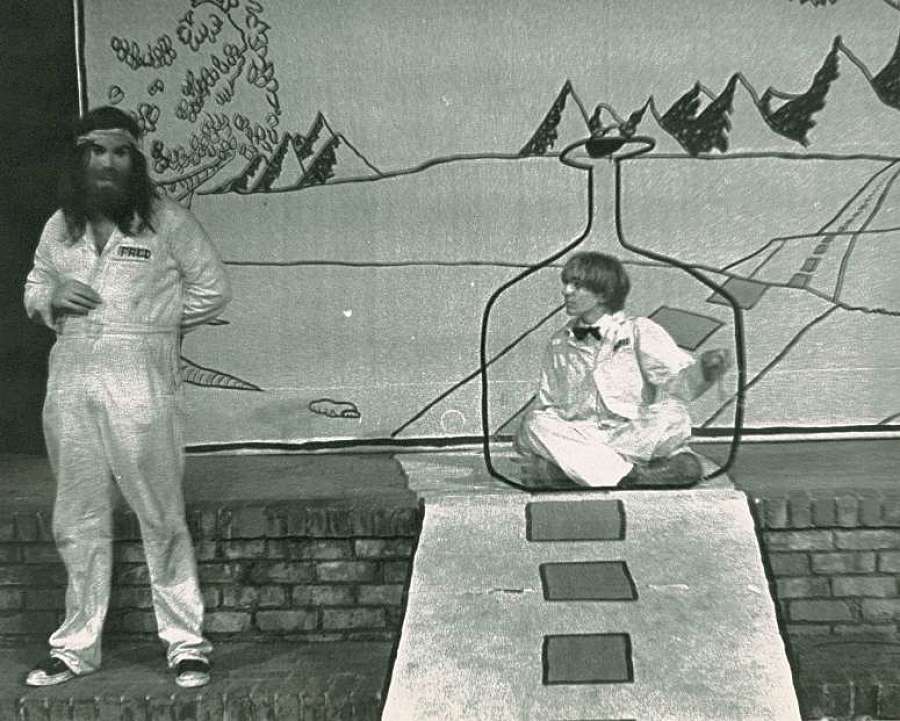

Robert Kelley was 20 years old and just out of Stanford when he and his fellow grads devised and staged an original antiwar musical called Popcorn at the Lucie Stern Theater in Palo Alto. That was in 1970, the same year Xerox opened a R&D lab in that college town, and just a year before journalist Don Hoefler coined the term “Silicon Valley” for the budding semiconductor industry that was taking root in the region and would soon transform it into one of the world’s central economic engines.

Next year Kelley will retire from the helm of TheatreWorks Silicon Valley, after having built it into an $8-million LORT fixture known for both new-works incubation and strong epic-theatre revivals. I spoke to Kelley about his remarkable 50-year tenure just days before the American Theatre Wing announced that TheatreWorks would be this year’s recipient of the Regional Tony.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: Congratulations on 50 years at the job.

ROBERT KELLEY: Thank you very much.

Take me back to 1970, that first season. What kind of space were you doing it in? The first show was an antiwar musical, is that right?

It was, yes. It was about the war and especially about our community here, which was very divided between generations. Our show was trying to find ways to bridge the gap between people, but it certainly started out with an antiwar demonstration. It became kind of an overnight hit, because just before we opened there was a huge demonstration and hundreds of young people were arrested in downtown Palo Alto. So we were almost a movie of the week. The show was a great big hit. It was a world premiere, but we didn’t call it that at the time. It was just the work that we had created to launch the company.

In those early years, actually for the first couple of years, we only did new work. And for the first five to seven years, a lot of it was in found spaces, restaurants and parks, nature centers. We did an Alice in Wonderland musical in an underground parking garage in one of our local buildings. It was a very fun time as we were getting started and experimenting.

Was Silicon Valley already a tech hub then?

No, but actually our growth curve as a company parallels almost exactly the growth of Silicon Valley as a thing. And I credit our success and durability as a company with the fact that we were in this unique area that was changing rather dramatically over time over this same period. It was becoming one of the most international and diverse places on earth, really. And diversity is one of the big commitments of TheatreWorks, one of our core values, and that was something that made the company, we think, increasingly attractive to people in the region. It was clearly a space that put a great deal of emphasis on creating new things. And our commitment to new work, we think, resonated very strongly with the ethos of the area.

We really kind of upped our game and in terms of new work in 2002 with the beginnings of our New Works Festival, which has continued since then; since we launched it, we’ve done 26 world premieres. That’s obviously quite a while after we began; next season will be the theatre’s 70th world premiere, with Paul Gordon’s new musical of Pride and Prejudice. We don’t exclusively do new things, but that has been a significant part of our growth and of our alignment with the spirit of this part of the country, of the Silicon Valley.

Has that proximity also helped you financially—have companies or individuals from the local industry been among your audience or board?

Definitely, being in this region which was generating a lot of wealth and a lot of people who were ultimately looking for a high-end experience, a professional experience, as opposed to anything else in terms of the arts, that was a niche we were able to fill. This is not a great area for corporate support, despite the huge number of tech corporations; most of their charitable giving actually goes outside of the Silicon Valley. But meanwhile, a large number of individuals were emerging or moving here that were part of the tech world, and we have found wonderful individual support for our work. That’s really what’s helped us to create a medium-sized regional rep in a suburban area. I think that might be a trend we were at the beginnings of, which may eventually be common across the country.

There are a couple of foundations that were very helpful for us also. There’s both a Hewlett and a Packard Foundation that have been very strong for the arts. They certainly helped us, but they’ve helped the arts throughout the region. And so that has also been a significant part of our growth.

My awareness of TheatreWorks has been in part your new-works focus, but also there’s been an emphasis on new musicals, right?

It’s definitely been part of what we do. Really from the beginning, one aspect of our work was a kind of a celebration of the intersection of music and drama. That doesn’t just mean musicals; it means music and the ways it can blend with serious drama, with comedy, with everything. As a result, we’ve typically done at least three music-theatre productions from the beginning over time, and in some cases more. It’s interesting, because certainly in the early years of the company, the first few decades, you could look around America’s regional theatres and not see a lot of musicals, really. It has become a much more recent phenomenon that they are being prominently done everywhere now. So there’s certainly been a sea change over the last 20 years.

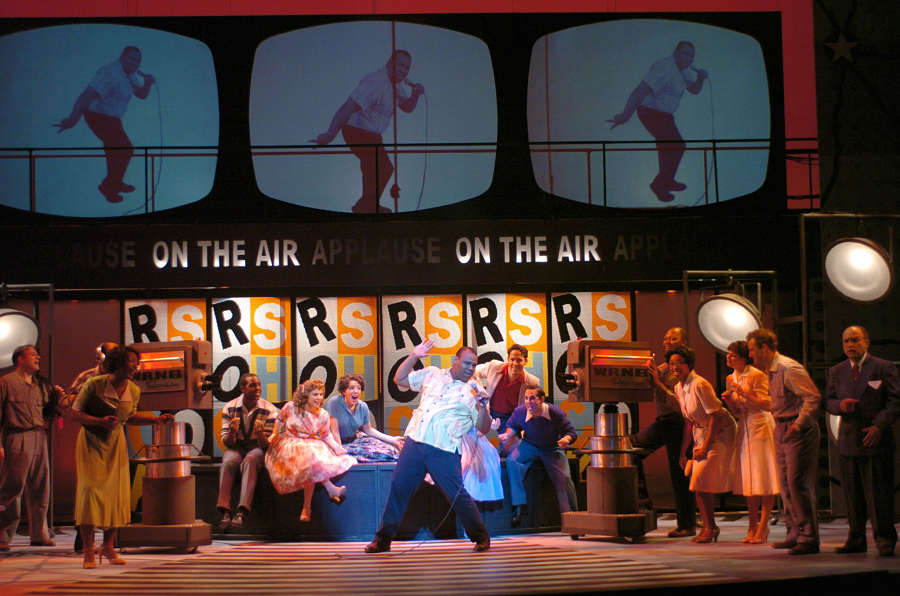

Certainly we had great luck with Memphis, which was in our very first New Works Festival in 2002. I actually directed the first reading of it. It then went onto our mainstage in 2004, then kind of lay dormant in the hands of a big producer, who finally passed away, unfortunately, and the piece moved on to Junk Yard Dog, which became the producer of it in New York and won the Tony in 2010. So that was pretty amazing. We thought it would take us four or five years of our New Works Festival before we’d see anything on the mainstage. We had felt we needed to build up our chops. But sure enough, in our first festival there was Memphis.

Interestingly enough, in that same festival we did a production of a dramatized version of My Antonia by Willa Cather, written by Scott Schwartz. Scott was an up-and-coming director at that time instead of a wonderfully established one as he is now. But just a few weeks before the festival, he called us and said, “I know it’s a drama, but it really feels like it needs some music to kind of create the mood.” And we said, “Well, okay, we’ll stretch and see if we can find someone to find or maybe write some accompanying music for it.” And he said, “Oh, no, I’m going to bring someone along if that’s okay with you.” And sure enough, he did. It was his dad, Stephen Schwartz.

Jackpot.

And he was there at our first New Works Festival, and wrote a complete score for this piece, which I doubt many people have ever heard. It was just beautiful. And we put it on two years later on the mainstage with music and a small orchestra to play it. We really formed a wonderful artistic relationship with Scott and with Stephen as a result; we did several other shows that Scott directed or that Stephen came and helped us put on, and it finally all came together in the world premiere of The Prince of Egypt here in 2017.

So you’ve definitely been part of the Northern California theatre scene, but you’re also obviously part of a national scene. How did that come about? Is it sheer longevity—that you’ve just been doing it a long time, so more and more people know you? Or have you made an effort to create a network of people and companies you’ve worked with over the years?

There are certainly people we know and have gotten to know over time, and some have led to world premiere productions. Paul Gordon—I think we’re up to five of his world premieres now. And certainly the relationship with Stephen. My own take is that we haven’t worked hard at being a nationally focused company. We’ve been proud to be who we are, and in some ways have been able to develop new work somewhat off the beaten path so that people could do things without feeling they were going to be swamped in a deluge of blogs analyzing their every move. And that has made it attractive here.

I did read about some lean times in your early days—that on one show your cast bought you groceries to keep you going.

That was our very first show, actually. There was almost no salary for me and I was just trying to get by. So for an opening night gift, the cast filled my car full of food. It was remarkable, and I actually lived on it for the better part of a year or so, dry goods and so on. It was a great way to start. I think of it as our first charitable contribution, the first philanthropy.

But it wasn’t that lean for long.

Well, it took quite a while for the company to become large enough to support people for real. We didn’t start as a professional company at all, and we gradually built ourselves first up into a community theatre, and then a big one, and eventually semi-pro, and finally into a LORT theatre in the early 2000s. It was a careful journey, but it wound up with achieving one of my dreams, which was that artists of all kinds, designers, actors, composers, and authors could make a living of some sort here in an area where it’s difficult to support yourself.

Was it always such an expensive place to live?

No. I guess you’d call it a standard California suburb at the outset. Not that it was ever easy to make a living in the arts, but of late this part of the Silicon Valley is one of the real estate peaks in the country as far as home ownership. I mean, it’s certainly a complex population of people of all kinds and all levels of wealth. But it definitely is a challenge for people who live close to our office or close to our theatres.

I want to ask about the audience. You’ve been there long enough to have seen generations of audiences come through the theatre. But are there some folks who’ve stayed with it the whole time? And do you feel hopeful that there’s a new audience that’s invested in what you do and will sustain the theatre?

I feel the theatre is rock solid all over the country and will continue to thrive. The audiences do tend to be older. People who have seen their children grow up and maybe gone to college are much more likely to have the time and the resources to be part of a season of plays. Younger audiences are coming to single shows; it’s pretty hard to explain subscription to anyone under the age of 30, maybe even under 40. But subscription continues to be the foundation of most if not all of the regional theatres in America. There’s turnover because audiences age, but on the other hand there are new old people made every single day.

That’s very true.

It’s not as if the audience is disappearing. There are a lot of things tied to the economy, and certainly theatres all over the country had to survive the recession and some unfortunately didn’t. But most did. I think our world of art creators is looking good these days and feeling strong.

Obviously the theatre hasn’t named a successor yet, but do you feel positive about the future? Are you going to come back and direct a few shows now and again?

I will. We’re not going to put any restrictions or obligations on a new person. We want an independent thinker. But I’m not leaving this area. I’m fiercely dedicated to the theatre, and I’m certainly going to do anything and everything I can to keep it going strong and be helpful in the transition. We’ve had a lot of exciting candidates we’re beginning to consider now, and I think we will end up with a very strong leader as we move forward. It’s certainly been amazing to watch the number of companies that have looked for or sought new leadership just in the last couple of years. So we’re in a kind of common territory with many of the companies around the nation as we do our search. I think change is going to be good for the American theatre. We’re going to see a whole lot of new leadership, and I think it will reinvigorate an already invigorated world of American theatre.

Apart from Memphis, which you already mentioned, can you name a favorite show or moment from your years at TheatreWorks?

I have a few shows that are favorites. We’ve done, I think, 21 Sondheim productions over the years, and my favorites have been Into the Woods and Pacific Overtures, which we’ve done actually twice and both times with remarkable success. I also have to say I love Ragtime and what it has to say. I love the music, but more than anything I love its embodiment of the essence of American potential even as it decries American prejudice and resistance to immigrants—that kind of mixed bag of welcoming but also spurning people from afar, and ultimately ends up celebrating the American dream. We had a wonderful production of it years back that was a landmark for the company, and I’ve decided to do it as my final musical at TheatreWorks next year. I kind of feel that a lot of the things we’ve had to say about the world and about America and about the human experience will essentially be summed up in that production and in that show.