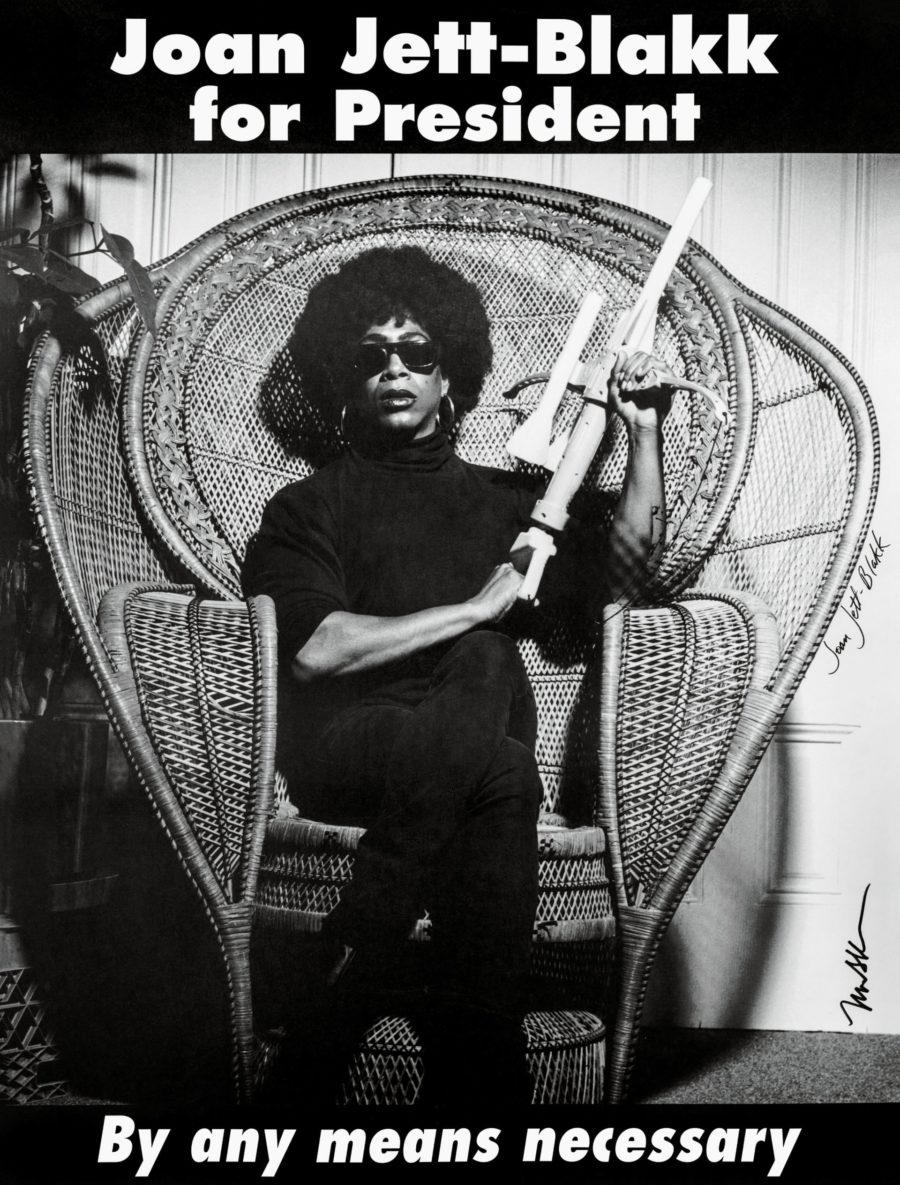

Before Pete Buttigieg, there was Joan Jett Blakk. In 1992, Blakk, a drag queen, became the first queer person to run for president under the banner of the Queer Nation Party, not long after first running for Chicago Mayor. Her “camp-pain,” as she called it (“Putting in the camp, taking out the pain”) was meant to raise awareness about the AIDS crisis and LGBTQ+ issues. Obviously Blakk did not win, though she did buck gender norms to announce her candidacy, in drag, on the floor of the Democratic National Convention.

This slice of queer history has since been forgotten by the mainstream. That is why this month, frequent collaborators director Tina Landau and Oscar-winning screenwriter and playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney, are bringing Ms. Blakk back in a new play they co-wrote, Ms. Blakk for President. Billed as “part campaign rally, part nightclub performance, part confessional—and all party!,” the play runs at the Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago through July 14.

In addition to cowriting it, Landau is also directing the show and McCraney himself is stepping into heels to play Blakk. If you’re wondering what the real-life Blakk thinks of all this, Terence Alan Smith, the performer behind Blakk, not only wholeheartedly approves; he was a consultant on the show. Smith, who lives in San Francisco, will return to Chicago to host a post-show series called “Late Nite with Joan Jett Blakk.”

I spoke to Landau and McCraney recently about why it’s important to remember activists like Blakk, and how theatre can help promote civic engagement (indeed, there is voter registration in the Steppenwolf lobby after the show).

DIEP TRAN: How did you both decide to have Tarell play Blakk?

TARELL ALVIN MCCRANEY: Tina basically wanted to do a project in which I did my own work or did a role in which I had helped create. So that was a given before we started writing the piece. This story is necessary. It’s about a queer person who decided that the world wasn’t paying attention, or giving enough attention, to the death around them and the sickness around them and the turmoil that was going on in their community. He decided to do something about it with love, light, humor, and agency. They took space where there was none. And I thought that was really compelling. Especially since I spend a lot of my time looking at my current political psyche or psychosis and feeling angry, bitter, and enraged; here was this person who found a way, through one of the most terrifying times in our history, to smile.

Joan Jett Blakk called her presidential run a “camp-pain”; it seemed like she was turning her candidacy into a performance. I feel like since then presidential politics has become more of a performance, and people become personalities more than real human beings.

TINA LANDAU: I think Joan began the campaign as a candidate for the Queer Nation Party, for [activist organization] Queer Nation. I think that the thing that was at the front of the action was less a performance and more of a political action. It was meant to garner attention and visibility for the queer community and for issues around AIDS. I think Joan and her cohorts were very aware of the time of politics as drag, as performance, as farce. They talked a lot about it in the time. Joan’s take was, “Well, I’m here creating a farce because that’s what our political system is.” The intent was to draw attention to exactly what you stated.

Tarell, what kind of research have you done to prepare for your role?

MCCRANEY: Listen to Tina. She had the good fortune of meeting Terence first and doing a 12-hour interview with him about that time. It’s really interesting, a lot of this story is hiding in plain sight. You could literally Google these words and they come up. For me, that’s one of the reasons why it was so important to do it—because this story was sitting right there and I never heard any part of it. Be it Joan Jett Blakk’s mayoral race or the presidential race in 1992, or getting on the floor of the Democratic National Convention in 1992. I had never heard of any of those things. I never heard of Queer Nation. I’d heard of ACT UP; as a kid I would see and hear about these activists who were chaining themselves to hospital beds. But I didn’t know the nuance that was there. I’ve also been watching documentaries and figuring it out. And remembering how to walk in heels.

Mainstream queer history is often very white-focused. Was the aim for this project to lift up a person of color who has been overlooked?

MCCRANEY: Yeah, I think for me as a Black person who identifies as queer, it really is important that I own up that a lot of my history has been taken from me and hidden from me. Some of it on purpose, some of it by way of just people dying and passing away. I think it’s important that we unearth that history so that we can continue the legacy of it. Because that means that there’s a legacy of Black political queerness in this country since its start, but it’s very hard to track down, and so if we let any part of it drop away for even a moment, our history will be skewed.

Joan lost that presidential campaign, as well as a subsequent 1999 mayoral race in San Francisco. How do you account for those setbacks within the piece? And what does the audience or the character learn from it?

MCCRANEY: I don’t know if it’s a setback to get onto the floor of the Democratic National Convention as the first Black drag queen candidate. I mean, there is something in the move itself that is bold and brought attention. For example, I think the way Queer Nation used the word “queer” and the way in which we use it now is evidence of the change they effected, the success that they had. I think in the play we wanted to shine the light on how those heels walking into that floor was an important moment.

I feel like coming off last year’s midterm elections, the message was that anyone can run, and anyone should be able to.

LANDAU: Yeah, very much. The piece is very much about, among many other things, representation. The question of, is our democracy and our electoral system really built in a way that offers a place at the table for everyone? It’s so interesting because they called 1992 “the year of the woman” at the DNC, there were so many female candidates [Ed note: The “Year of the Woman” in 1992 was actually in reference to the record number of women elected to Congress]. So there were crazy parallels that are like: Gosh, so much has changed, and yet nothing has. We’re still dealing with the same issues. It was funny, recently Terence said to me, I forget what candidate we were talking about, but they were kind of touting themselves as the first gay candidate for president—

Pete Buttigieg?

LANDAU: Yeah, it might have been him, and Terence was like, “What is he talking about? I ran in ’92.” I think Terence’s story is very much about the desire and the impossibility and the dream and the necessity of participating as a full citizen in this country, which is not always a given for too many people.

How did you settle on the format of presenting it in an immersive experience?

LANDAU: It’s my taste these days. I’m not really interested in theatre where I go see a play that’s in a little square box that I’m removed from, that doesn’t reach out and speak to what’s actually happening. Part of it just stems from Tarell’s and my shared interest in the live event and capitalizing on what theatre does best, which is create an experience that actually occurs, in which something actually happens in the time you have together in a room. And it just seemed like the spirit of Queer Nation and the spirit of Terence/Joan was a political happening and a party. That’s what the DNA of their actions were and it felt appropriate to say, “We will meet that and match that and transfer that to our time in the theatre.”

Tarell, you’re nominated for a Tony this season for Choir Boy, and Tina you were nominated for a Tony last season for SpongeBob SquarePants. Do you think the mainstream is becoming more friendly to artists like you?

MCCRANEY: I don’t know. First of all I have to be candid by saying I have always kept the idea of Broadway or commercial theatre quite separate from the work that I’ve done. For example, Tina and I did not have a play six months ago that was written down. It’s so new that we couldn’t give it to you for an interview for press. That just wouldn’t fly in the commercial industry. If we were going to be meeting press at this juncture, they would want to be handing out scripts and want to be having conversations in specific ways.

The work I need to do for my own spiritual upkeep has to have a kind of nimbleness to it, for a lack of a better word. I think for me in the way in which the play came about, the vocabulary of the play, the way in which it moves through time and space, feels very much like theatre of necessity, of what we need to tell this story, and not formulas in which we will aim toward an audience laugh every three pages, or whatever the very necessary formulas for commercial work can be.

I think that audiences are always up for shifts in models. I think that’s why they both come downtown and to Off-Broadway and to Broadway. I think specifically in Chicago, you’ll see people who go to see Broadway in Chicago and come to Steppenwolf and go to storefront theatre.

LANDAU: I’m thrilled that on the one hand there’s a certain kind of representation of different kinds of artists, of different backgrounds and colors, etc., represented on Broadway. But I also think there’s a long way to go. It depends what side of the statistics you’re looking at—like, there’s so much great representation in one area, but then you look at the gender of directors or the race of designers.

MCCRANEY: And who’s nominated and who actually wins.

LANDAU: Right. What I appreciate about a lot of the works that have come to the floor—I’m thinking of Choir Boy, Hadestown, What the Constitution Means to Me—these are pieces that were developed for their own end. They weren’t aiming for Broadway. I’m happy to see that. I think what we’re learning is that if we stay true to ourselves and make the work that matters and work really hard at it so that it gets good enough, some of these pieces have a shot at a broader audience. Which is what we want.