Jeff Daniels’s ground-floor dressing room at the Shubert Theatre has the feel of a tiny New England cottage, its clapboard walls adorned with canvas photo prints of family and pets; a floor lamp, divan, espresso maker, and acoustic guitar only complete the sense of a comfy but temporary home away from home, a gentleman’s man cave. It’s here that Daniels, a quintessential Midwesterner who learned his craft on the New York stage but made most of his money in Hollywood, cools his heels before going onstage eight times a week as an Alabama lawyer in To Kill a Mockingbird.

“This is one of the rooms Bette Midler had,” said Daniels of the Hello, Dolly! star who previously headlined the theatre. “She had a couple other rooms as well, but then she had many more costumes and wigs than I do.”

Daniels employs no wigs at all, in fact, to play Atticus Finch, a role for which he is nominated for a Tony, along with two of his castmates, the play’s director, Bart Sher, and the show’s designers—but not, conspicuously, Aaron Sorkin, the writer whose new adaptation of Harper Lee’s iconic 1961 novel has broken box-office records to become the most successful American play in Broadway history. Acclaimed by most critics and embraced by audiences, the show also has some detractors, who either deplore Sorkin’s departures from the beloved novel or see the whole project as a misguided racial whitewash, a theatrical Green Book.

Both critiques have merit but sell Mockingbird short: Sorkin’s adaptation isn’t just dramaturgically smart, it’s also more complicated than a simple white-savior narrative. For one thing, Sorkin’s Atticus, though centered in the play more than in the book or the film, isn’t quite a hero. He doesn’t just lose the case to exonerate a falsely accused Black man, Tom Robinson; he also consisently, even pigheadedly, reads his town and his time disastrously wrong, believing mistakenly that the goodness buried deep in everyone, even the unrepentant racists, will somehow awaken in the light of reason and triumph in the end. The way Daniels—in many ways one of our best not-quite-the-hero actors—etches his own take on a character previously imprinted by Gregory Peck is to double down thanklessly, even self-effacingly, on Atticus’s stubborn, blinkered liberal righteousness. We can tell he believes what he says in good faith, even as we—and most of the rest of the characters in Sorkin’s wised-up adaptation—can see how Atticus’s fine ideas aren’t just insufficient to the urgency of his moment, they may in effect be part of the problem. It’s that sense of disproportion, between an outrageous injustice and an ineffectual response of “good” people to it, that places this Mockingbird squarely in our Trumpian age.

In an interview in his dressing room before last Friday night’s show, Daniels was clearly feeling both the weight of the role and some of the fatigue of a Tony campaign that had him perorating about the show’s meaning on Lawrence O’Donnell’s MSNBC show the night before. At 6’3”, he’s the kind of tall, taciturn Michigander who doesn’t seem imposing unless he wants to be, but when he leans into a point, you definitely feel it.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: How’s this run going?

JEFF DANIELS: We’re still a hit. We start our eighth month tomorrow.

Are you counting?

I am. We started Nov. 1—we count previews around here. We had 45 of them. The official record will say opening night was performance No. 1. That’s crap. That was performance No. 46. We opened middle of December, and tonight is number 239. I only know because I’m looking at 250 which is, I think, the Tuesday after the Tonys.

When are you done?

I’m done in a year, on Nov. 3.

Will that be your longest run on Broadway?

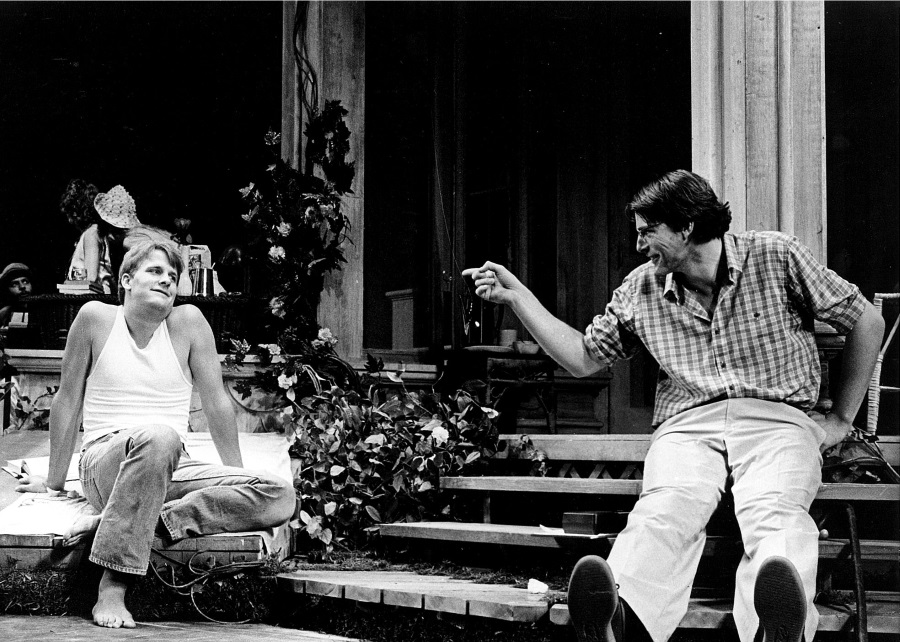

Well, Fifth of July, back in 1980; that was seven months. And God of Carnage was March to Thanksgiving, but we took August off because James Gandolfini wanted to go to the Jersey Shore.

Then you later went back into that show and played Gandolfini’s part, an extraordinary acting feat, and that gets me thinking about your “type.” Until Atticus, and maybe Will MacAvoy on “The Newsroom,” I hadn’t thought of you as the kind of actor who gives big speeches or blows his top. I wonder if you think the role switch you made in Carnage, from basically playing the nebbish to playing the heavy, sort of crystallized that transition?

No, that’s crap. That’s something a critic would say.

Well, that’s me.

There is no plan to it. What happens is that you get out of the gate in Terms of Endearment, and that’s who you are. You’re not going to be a leading man after that. So now you can play the guy who’s in trouble: Something Wild or Purple Rose of Cairo, where you’re a leading man, sort of, but you have flaws and you fall. You know? So now you’re playing interesting people, like Jack Lemmon did. He never played the square-jawed hero. You wouldn’t buy that anyway, because his strengths were elsewhere, and he liked to make it complicated. I was always headed toward that, and then I started doing comedy because I can, and I think that it’s equal to drama, and it is. Then along comes Dumb and Dumber, where you completely blow up whatever your brand is, and it worked. And then it’s 10 years later and you get The Squid and the Whale, and you get God of Carnage, and then Netflix, and HBO, and Showtime happen, where the writers are king and queen. They get to write complex characters that last over eight episodes, which is like an eight-hour play or an eight-hour movie, and now you’re playing complex people.

And “The Newsroom” comes in.

That was something that Aaron wanted to write, and physically I fit it. The one thing he did say was, “I’ve never seen you get as angry as McAvoy has to get.” So I told him a story about this production we’d had and what I did; I was in the Four Seasons Hotel at a breakfast meeting with Aaron and Scott Rudin, and I pounded the table and glasses moved, and Aaron’s going, “I got it. I got it. I got it.”

You can do anger.

“Oh, that’s what you need? Yeah, I can do that. Nobody’s asked.” It’s not this: I need to do seven plays or projects where all I do is rant. That’s shit. It really is. You put Atticus in the same diner with Will McAvoy; they’re two different guys. And The Looming Tower guy, and then you bring Frank Griffin in from Godless. That’s the fun of it for me, and that’s what the theatre has always taught us. We’re not supposed to do what we did before. You’re starting fresh each time. That’s the direction that theatre has always pointed me in. And it’s not until you get to Hollywood that you hear, “Could you just do the same thing?”

Right. Do you feel like maybe accumulating that sort of repertory company of characters within you is what, after all this time, gives you the weight to stand centerstage and be Atticus?

Well, I’m Atticus, and I’m not Gregory Peck. We’re not putting him on Mount Rushmore on page one. You get him at eye level; that was part of the risk Aaron took. He’s a small-town lawyer who gets paid in vegetables, is raising two kids without a wife, and does land disputes, service agreements, foreclosures. That’s what he does. A judge comes over one day and changes his life. Says, “It’s a no-brainer, the guy’s 100 percent innocent. Even a white Christian jury, you’ll get one guy to go, ‘Yeah, you’re right. He’s not guilty.’ Go help this guy. Keep him out of prison for 18 years.” “Okay. Yeah, all right.” That’s who he is.

You make it sound pretty matter-of-fact.

It’s pretty simple. It’s small-town.

That’s the way he thinks about it, but everyone around him—and we—can see that he’s mistaken. This guy is not going to get off, and there are real, irredeemable racists in his town. Everyone seems to be ahead of him on this point.

He’s just digging in. His beliefs are as strong as the rule of law and taking an oath to tell the truth. Frank Johnson was a federal judge that could have been Atticus grown up. Real guy. He would toast people saying, “To the Constitution.” That’s what Frank did, and Atticus was that strong. When Mrs. Dubose has her racist rant, and Atticus says, “She’s a sick old lady, and it’s the morphine talking”—he thinks there’s goodness in everyone, and you just have to get through the weeds to get to the goodness, even in Donald Trump. That’s Atticus’s belief. That’s being questioned now today, and the people in the play turn to Atticus and go, “You’re not going to get what you want by sitting around the porch saying, ‘Everybody’s got a better angel.’”

The line that pops out for me is when he tells Scout, “Yes, I’m a 100 percent right and they’re a 100 percent wrong, but they’re still good people.”

They’re still our friends and neighbors, yeah. They’ll come around. You don’t have to change everybody today.

Let me ask: How do you as an actor play against something you know? Not just in the sense that you know the ending of the play, but in the sense that you might know better than your character?

Well, I’m not there. It goes back to Circle Rep. It’s so simple. Marshall Mason would preach, “What are your given circumstances? Not only going into a scene, but each moment: What do you know? And forget what you don’t know. Forget what you think you know. Forget what the actor knows. We don’t care.” I mean, is there some, Oh, I better set that up for later, and so you point the performance to there? Yes. But once you’re in that moment, that’s what makes it easier to do in your eighth month—there’s an innocence going in moment-to-moment. Meryl taught me that. She’s nowhere else except present. And when you work in the present, and use the other actors to push you into the next moment, you aren’t playing anything else except what’s going on right then.

In this staging, the jury seats onstage are empty, and at one point you basically turn to the audience and give the speech to us, as if we’re the jury. Is that the idea?

Definitely. They’re the jury. When you turn, you know it’s a theatrical device, and that you’re seeing 1,435 people’s ears pinned back, because suddenly he’s turning to you and guiding you in a very strong way: We have to heal this wound, or we will never stop bleeding. I’m talking to you, all you white people sitting in your Broadway seats. And of course Tom Robinson doesn’t get off, and the audience feels it, which is different than the movie, which you watch, or the book, that you read and put down. You feel it. It’s the use of that direct address, and then coming out of it and pulling you right back into the courtroom, that spins the audience who thinks they know this story.

What makes the play unsatisfying, in a way—I don’t mean unsatisfying aesthetically, but morally—is that there’s not the kind of closure you get in the film or the book, I think.

What’s the moral closure in the film?

Though Atticus doesn’t win, you feel his way is right, ultimately, and if we could all just be like him, it will all work out. That’s not what you get from this version; his approach is not vindicated.

Correct.

He just tragically can’t see it. I think he does glimpse it, a bit, but by then it’s too late.

Tomorrow. It’s about tomorrow. And that’s what Sorkin, I think, is saying; it’s not about today. It’s about what you’re going to do tomorrow, America. It’s time to get off the porch!

Did you have an Atticus in your life?

My dad was the closest one. He really was the guy in a small town who was: There’s the right way and all the other ways.

Was there a point you sort of saw through or questioned him, or rebelled?

That’s a great question. Because Dad—man, he was generous. Man, he was kind. I’d gone to New York, and later in life I would tell him stories of how I had to make it in Hollywood, and how you got to go nose-to-nose with an asshole producer, and this is what you have to say, and you have to quit the project, and see if you’re called tomorrow morning. “I can’t just sit there, Dad, and have a gentle conversation about what’s right to do here.” And it’s the same thing Jem and everybody else are saying to Atticus: “You can’t just sit there, you got to fight back. You got to fight for what you believe that is right, good, and decent, all that stuff.” My Dad was, “I know you think I’m too nice to people.” I said, “Dad, I went to college on the streets of New York for 10 years in a business that is cruel, so, no, I don’t think you’re too nice to people, but you could throw a right hook once in a while.”

What’s the key thing you learned from working with Lanford Wilson at Circle Rep?

He and Marshall were the first true artists I ever met. I didn’t know what that was until I came here in ’79. I was 21 years old. Lanford wouldn’t doctor screenplays. “I’m a playwright.”

He wouldn’t take the easy buck.

Wouldn’t do it. He might teach at a college. He might do a speaking engagement. But he would not take a screenplay job. I said, “Lanford, it’s six figures and your name’s not even on it.” “No. I won’t do it. Movies are bupkis.” That allegiance to his art was to be admired. He never told me what he thought of Dumb and Dumber.

Circle Rep was the model for your own company, Purple Rose, in your hometown of Chelsea, Mich., wasn’t it?

Yes. Usually Circle Rep revolved around a one play a year by Lanford. He was able to write one a year, and I took that as the model for Purple Rose. There was a period of, I don’t know, 10 years or so where I wrote one a year. The thinking was, we need one from me because they will come to see a play I write, and I got to get them into the theatre.

How’s Purple Rose doing?

We’re stronger than ever. The board of directors we have is the best we’re ever had as far as involvement and support, and not only financial, but emotional and creative. We’re into an endowment now, and we’re still bringing people to the theatre who’ve never been to a play. As often as possible, we try to hold a mirror up to them. That’s what I keep telling the playwrights: I’m not interested in what you think. I’m interested in what you think about what they think. Show them themselves. They will identify. They will be pulled in. Reflect the times, whatever it is you want to write about, but use them. Don’t write something that you hope goes to New York. Don’t write something that really should be a screenplay. Hold up a mirror to these people.

That’s why I wrote Escanaba in da Moonlight, about five guys deer hunting in Upper Peninsula. They came in droves. We had people showing up, 12 men in their hunting gear, camouflage, hunting tags on their back, sitting in row G, seeing it for the fifth time. Those are the people you want to get in the habit of going. The American theatre, with all due respect, often has its head up its ass.

I’m not the American theatre, I just write about it. Go on.

I mean, I used comedy. The last time I looked, the Greeks were holding up two masks. Why not? If you can write funny and tell a story, like Escanaba, or I did this play Diva Royale last fall, about three Midwestern housewives who go to New York City to see Celine Dion, and everything that can go wrong goes wrong. It’s a little bit modeled after Jack Lemmon and Sandy Dennis in The Out-of-Towners, but it’s like Neil Simon on acid. It was the largest-selling show in our 28-year history. Guy Sanville, who’s the artistic director—he’s like the Marshall Mason for me. I write the play and Guy directs it. I’m writing one for January, and Guy’s coming here in July, and we’re going to work on it. There’s a draft in already, and then it’s like the pony’s up on its legs.

Did you have anything like that when you were growing up there?

No! There were two stoplights. There’s a documentary on the internet somewhere about the Purple Rose, and they interviewed all these people about what the theatre has done for this little town. When we opened the theatre in ’91, there were 25 businesses downtown, 12 of them were empty. Now you’ve got restaurants. You’ve got hotels. You’ve got B&Bs. You’ve got art galleries. You’ve got a bar with music afterwards. And the guy who runs the furniture store comes over and says, “We have sold so much carpet and couches. We sold a couch. A guy came in. He said, ‘I was seeing the play, and I said that’s a great couch, and we had a price on a couch over where we live near Detroit, and we bought a couch.'”

That’s amazing.

The guy who runs the furniture store loves the theatre. He loves it.