If you close your eyes in the backstage wings of the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, you can almost fool yourself into thinking you’re on a country farm. You can hear sparrows tweeting and waterfowl squawking and, off in the distance, the sound of hunting rifles piercing the bucolic serenity. Though from the audience these sounds are just gentle, drifting reminders that The Ferryman is set on a farm in Armagh, Ireland, from backstage the soundscape is enveloping. And if you open your eyes, the farmland vanishes; with all the warm-up activity and foot traffic around you, it feels more like you’re at a pumped-up pep rally.

For a few performances, I got a peek (and a listen) at the backstage action of Jez Butterworth’s sprawling, three-and-a-half hour drama about a farming family in Northern Ireland preparing for the annual harvest in the summer of 1981, as the “the Troubles” are coming to a head. In the shadows with me was the talented artist Michael Arthur, as we observed the Tony-nominated play from wings, the dressing rooms, the green room, even the animals’ quarters. I can attest that there is as much excitement backstage as there is onstage, possibly even more. How could there not be, with a cast of 21, plus a few geese, bunnies, and adorable human babies?

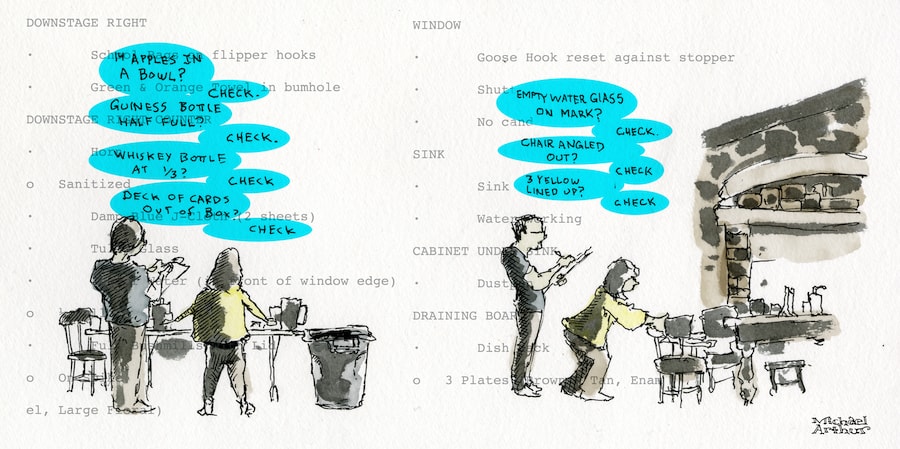

Before the show, the crew members set props and prep food. The stage managers Morgan Holbrook and Shelley Miles, led by production stage manager Jill Cordle, have a counting system for making sure the overwhelmingly long list of props are in their respective places on the prop table or set onstage. This tried-and-true system, a holdover from the show’s London run, quickly taps through apples, Connect 4 pieces, candles, water glasses, and more.

Indeed the entire backstage process has been informed by the show’s original London crew, though some U.S. union rules and regulations differ from the U.K. For example, stage managers in the U.K. are also the props folks and can move set pieces. “In America, stage managers are more big-picture,” Holbrook explains. “It’s more about making sure that everything runs smoothly, that people are where they need to be, and problem-solving as things come up.”

The props team has more than enough on their hands. Props master Clem Zajac prepares the show’s 16 beer bottles: the Guinness bottles, filled with water and black food coloring, and the Harp Irish Lager bottles, filled with non-alcoholic beer to achieve foam and bubbles. The play’s director, Sam Mendes, “likes the realness of things,” says Zajac.

The verisimilitude extends to the onstage food; actors cook eggs and bacon onstage in the set’s kitchen. For an actual onstage feast in Act Two, Zajac prepares potatoes roasted in goose fat (a customary cooking method in Ireland), as well as mashed potatoes, vegetables, and a turkey—actually a prop turkey layered with roast beef for the actors to eat. “This is one of the biggest consumable shows I’ve ever been on,” says Zajac, pointing to the bags of groceries delivered weekly. There are bushels of apples, boxes of teabags, candles, herbal tobacco, pre-rolled herbal cigarettes, and jars of goose fat lining the shelves.

Upstairs the wardrobe team prepares costume pieces and cast members are equipped with microphones and wigs. A rousing singalong of “Baby Shark” erupts. Ralph Brown, who portrays IRA heavy Muldoon, is feeling under the weather. “I have a cold, but Muldoon does not,” concedes Brown as his mic is placed. He credits “Dr. Footlights” for his miraculous recovery onstage the night before, which halted his sniffles. He’s equipped with a handkerchief from the wardrobe team just in case.

In the hallway, the cast’s youngest girls wait their turn for the wardrobe chair. Brooklyn Shuck, who plays Nunu Carney, says the constant supply of dried mangoes, throat lozenges, and Tootsie Rolls backstage keep the cast energized through shows. The girls busy themselves trying to guess the middle name of fellow cast member Fred Applegate—a game the whole cast has been occupied with for months.

“Backstage there are so many actors, baby, geese, and crew people—there is a choreography of its own back there,” says Ashley Simeone, one of the show’s three dressers. “It took all of tech and all of previews to sort of figure out where you can stand in what moments.”

As the audience fills the house, the cast readies in the wings—and crew members find their out-of-the-way corners. Brian d’Arcy James, the show’s lead, stretches before his entrance. Shuler Hensley places apples in his pockets alongside his scene-stealing partner, a Netherland Dwarf rabbit named Pierce. And Michael and I perch on folding chairs in the dark, taking in the adrenaline rush of pre-show excitement.

Before Act Two we make our way to stage left to see what the cast and crew call the “baby business meeting.” Two babies, with their parents in tow, wait backstage before the show resumes post-intermission; one is on standby. Coos and oohs and ahhs fill the wings. Stage manager Jill Cordle, who holds court at stage left for the show’s entirety, welcomes the babies into her solitary corner of screens for a much needed reprieve mid-show.

On stage right, things get dirty. The goose Peggy (the show also has Gertie, who switches off for performances) hovers above a tarp for makeup. “The geese have different personalities,” says Hensley. Peggy the goose is nestled under his jacket as globs of mud are placed on her feathers, her webbed feet swimming in the air. “Peggy is a little bit more calm, in general, and Gertie is a bit more vocal,” he says of his castmates. “They have slightly different habits onstage too,” adds Eric Mitchell, the show’s animal handler.

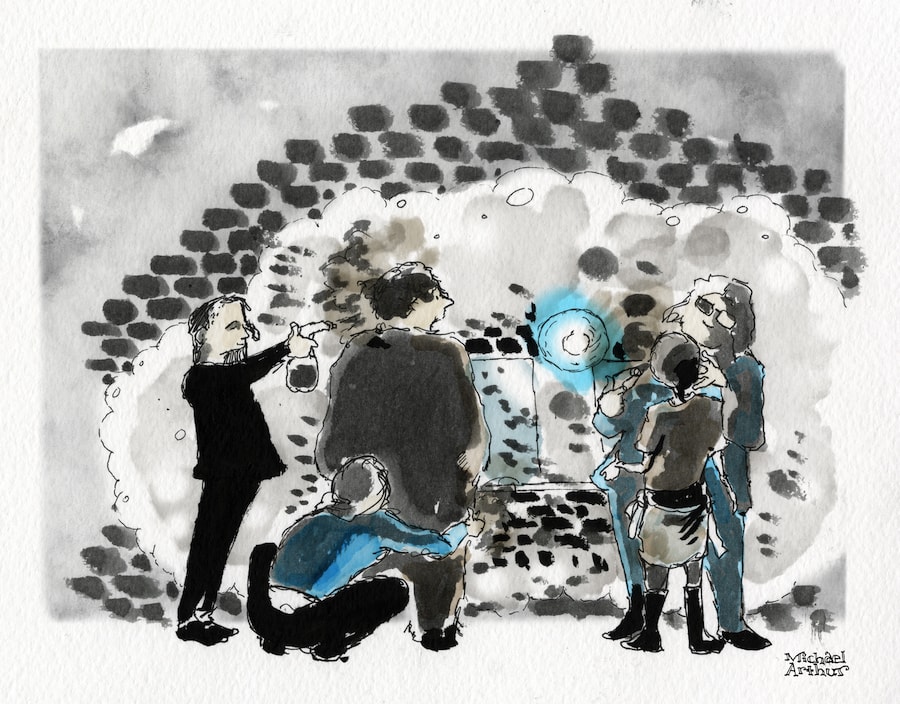

Backstage the Carney boys get muddied up too. “This is my favorite part of the show,” whispers Lauren Hanson, a member of the wardrobe team. She’s armed with spray bottles of water and a bandolier of bobby pins. Cylinders of brown makeup powder line the backstage vanity. She’s got a different routine for each of the actors, fit to their personalities, like an individualized handshake. The application of dirt looks like a choreographed dance, with spins and extended arms resulting in sweaty armpits and dirty clothes. “It’s always different, fun, and silly,” she says. A cloud of powder forms, and suddenly the Carney boys look like they’ve just come from a day in the fields bringing in the harvest.

“1, 2, 3!” quietly shouts Sean Delaney (Michael Carney), and 14-year-old Michael Quinton McArthur (Declan Corcoran) drops into the dark of the stage right wings and does 10 push-ups. He’s egged on by his older onstage brothers to do more, but he demurs: “It’s a two-show day!” A team huddle has formed now, and the boys count down before loudly bursting into the Irish folk song “Monto,” then run onstage—a cloud of dust behind them.

Downstairs, the offstage characters are enraptured in a game of Bananagrams. The word-play game “is a staple, at least two games a show,” says Trevor Harrison Braun, one of the show’s 10 understudies. “There is a lot of real down time,” says Ann McDonough, the cast’s Aunt Pat. “It’s very Shakespearean—Shakespeare always gave his characters a nice long break.”

“The stool is coming, kids!” effuses McDonough and the attention directs to a screen. At each performance the offstage cast gather around the screen displaying the performance upstairs to see just where a stool, thrown in a fight scene, will land. Bets are placed if it will ricochet upstage, downstage, or, worst case scenario, into the front row as it did a few weeks ago (there were no injuries!). “This is what I live for,” says understudy Griffin Osborne with a laugh.

Peggy the goose wanders in and stretches. The Carney girls Bella May Mordus, Willow McCarthy, and Brooklyn Shuck use the Act Three break to choreograph impressive dance routines. Osborne is shopping for furniture; Braun resorts to studying for finals. Soon the ceiling begins to rattle from the sound of howling Banshees, and everyone’s attention returns to the action onstage. The sounds rouse the backstage crowd and they ascend the stairs for the curtain call, accompanied by another howl—the enthusiastic audience.