I love a good romantic comedy. My favorite is When Harry Met Sally, which I first saw when I was 13. Even now I can still recite the entire film from memory. I wanted to be Meg Ryan, Julia Roberts, or Sarah Jessica Parker when I grew up: opinionated, with a take-on-the-world-in-heels attitude. It didn’t matter at the time that they were white and I wasn’t. And it only sort of mattered that every time an Asian woman showed up, she was usually doing a white woman’s nails or serving her dinner.

But I didn’t see myself as a quiet sidekick, a hypersexual prostitute, or the invisible servant. I was the hero. And if the hero was a white girl, I could be the white girl.

Then in 2015 I saw a Pacific Playwrights Festival reading of Vietgone by Qui Nguyen, a play about how his parents, Tong and Quang, met in a refugee camp and fell in love after the Vietnam War. I’m Vietnamese. My family are also Vietnam War refugees. It was the first time I had ever seen our story represented in American entertainment. I laughed, I cheered, I rejoiced in the display of Asian excellence and sexiness onstage. I even teared up a little bit.

There is a line in The Scarlet Letter: “She had not known the weight, until she felt the freedom.” I hadn’t known the weight of transposing myself into other people’s bodies until I no longer had to do it. There’s a certain mental gymnastics all marginalized people do when they see another body onstage (usually white, often male). It’s an unconscious impulse: “This is the person I have to relate to; I will pretend to be this person for the next two hours.”

When you’ve had to pretend to be someone else for so long, there’s freedom in being able to just be yourself. That’s why, in the span of two years, I saw three different productions of Vietgone (in California, Oregon, and New York City). I wasn’t the only one obsessed with Vietgone. Since 2015, Nguyen’s play has been produced 14 times around the country, with 6 upcoming, according to rights holder Samuel French. In tandem with the runaway success of Crazy Rich Asians, it’s clear audiences are ready for a splashy Asian romcom.

This past April I traveled to California to see Poor Yella Rednecks, the sequel to Vietgone, also as part of South Coast Repertory’s Pacific Playwrights Festival, though this time it was a full production. South Coast Rep stands a mere 10 miles from the house I grew up in, where my parents still live.

As Nguyen told me when we spoke for The New York Times, he plans on writing a five-play series about his family’s journey to America and their settling down in El Dorado, Ark. His second play, Poor Yella Rednecks, finds Tong and Quang living in Arkansas in 1981. If Vietgone is partly about the euphoria (and messiness) of new love, Poor Yella Rednecks is about what comes after the happily ever after. It’s an anti-romcom, with a dose of immigrant existentialism thrown in. In one scene, Tong talks about trying to communicate with her son’s teachers, only to be met with condescension. “I tried to talk to them about it, and they just stare at me with those dumbass smiles, like I’m too foreign to understand when I’m being talked down to,” she says. If everyone looks down on you and treats you like you’re invisible, do you really exist?

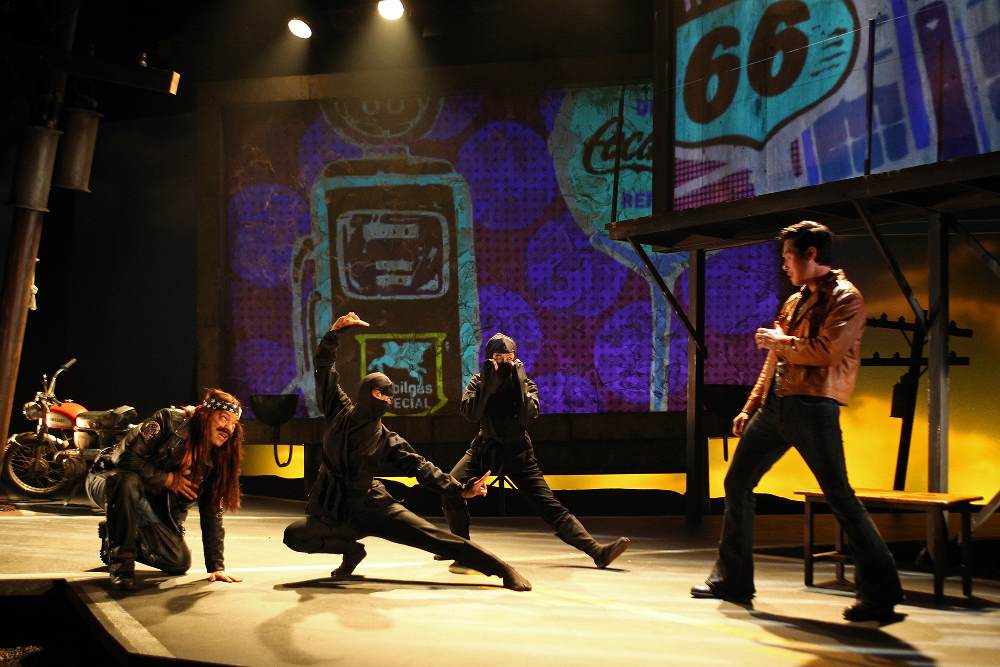

Though Poor Yella Rednecks contains the essential elements of a Qui Nguyen play (kung-fu, profanity, rap songs), it is also a more serious work. The problems these characters have—living in a country where they don’t speak the language, working minimum-wage jobs where they’re harassed and disrespected—won’t be solved by spin-kicks but with grit and ingenuity. In Vietgone, I saw something close to the stories my father told me when I was growing up, about the Vietnam War and its aftermath. In Poor Yella Rednecks, I got to see something even more personal: my own story.

I was born in Đà Lạt, Vietnam, and my family immigrated to America when I was 2. In one photo in the family albums, I stand by myself, crying, my mouth open and eyes wide, looking directly into the camera. My parents told me that as we has boarded the plane in Saigon that would take us to California, I kept sobbing, saying, “I want to go back to Aunt Tám’s house.”

Vietnamese was my first language. When I think back to my earliest memories, the scenes at home are clear and the scenes at school are cloudy, with white adults who sound like the grownups in Charlie Brown specials. In one memory, I’m sitting outside of the principal’s office in kindergarten. The grown-ups are talking to me, and they’re speaking so fast I don’t understand. I know I’m in trouble, but I don’t know why. I sit there for an hour as people go in and out of the office. Finally a Vietnamese man comes out and sits next to me. He says, in Vietnamese, that someone had complained about the necklace I was wearing, a gold Buddhist swastika, a gift from my mom. I guess they thought I was a Nazi. I didn’t wear that necklace again, and I realized then that to fit in, I had to leave some parts of myself at home.

Little by little, as English became clearer for me, the Vietnamese receded to the background. In 2001, when we went back to Saigon for the first time in 11 years, Aunt Tám said to me, “You speak Vietnamese like a foreigner.” Vietnam has a word for those who live abroad: Việt Kiều. Those of us who have a hyphenated identity are foreigners wherever we go.

In Poor Yella Rednecks, we see the heavy price assimilation exacts: loss of home, loss of culture, loss of language. One of the play’s threads follows a young Qui Nguyen, who is bullied in school and has trouble learning because he barely speaks English. The teachers recommend that Tong and her mom, Huong, speak only English to him at home. The tragedy is that Huong doesn’t know English, and taking away Vietnamese means she can’t fully communicate with her grandson.

“What happens when he learns English so well that he doesn’t think in Vietnamese anymore?” asks Huong. “What happens when his insides no long match mine? What happens when he looks at me the same way the people here look at me? Like I’m less. Like I’m invisible.”

Tong’s answer: “We either assimilate or die.”

If Vietgone is primarily about leaving Vietnam for a new country, Poor Yella Rednecks is about the formation of that new country, which we can call Asian America. In one scene the characters travel to Houston, which in 1981 was only starting to become a Vietnamese enclave. Today there are almost 40,000 Vietnamese Americans in Houston, out of 1.3 million in America. The only thing separating a Vietnamese immigrant in 1980 from an Irish immigrant in 1880 is time. For better and worse, eventually this land makes Americans of us all.

That’s not to say Nguyen’s plays are perfect. In both Vietgone and Poor Yella Rednecks, the rap songs lack polish and sometimes slow down the action. Poor Yella Rednecks, unlike the more streamlined Vietgone, also suffers from a surfeit of plot (the South Coast production was the premiere; it will play in 2020 at Manhattan Theatre Club and at Oregon Shakespeare Festival). There are three different narrative threads at play and, though I laughed, I also left feeling emotionally fatigued.

But despite its flaws, Poor Yella Rednecks does something more groundbreaking even than Vietgone: It positions Vietnamese immigrants independent of the Vietnam War, in the process making the case that we are just as American as anyone in the audience. It does this most ingeniously through language: the Vietnamese characters speak perfect English while the white characters speak gibberish like: “Yeehaw! Get’er done! Stevie Nicks!” We are meant to put ourselves into the shoes of these refugees as they face and overcome adversity. Rooting for the underdog: What’s a more American pastime than that?

My main criticism of the popular musical Miss Saigon has always been of its treatment of its Vietnamese characters. That show is not made for us to see the world through their eyes. They are foreigners, people “over there,” who “we” (Americans) failed to save. For a war that killed 3 million Vietnamese, the prevailing narrative in the U.S. has always been about how Americans feel really bad about it. In this narrative, and in so many Hollywood films, the Vietnamese body is a vessel for white guilt.

Then again, treating Asians as concepts instead of people is common in Western culture: Whether it’s Madame Butterfly, The King and I, The Last Samurai, or the upcoming films A Thousand Paper Cranes and The Greatest Beer Run Ever, Asian stories only have validity if white people are involved. This is not to say non-Asians can never write Asian stories. But if white authors are trying to listen to another community and tell their stories with authenticity, they shouldn’t insist on inserting themselves into the center of those stories. In this paradigm, bodies of color become either a tool to teach white people a lesson or victims for them to save.

If Vietgone turned that narrative on its head by repositioning Vietnamese people as survivors who can love, laugh, and fight as well as any white person, Poor Yella Rednecks makes the case that these people are your neighbors. Instead of a foreign “them,” they are part of an us, part of the fabric of America. This play defines “Vietnamese” as something more than “war refugee.” In Vietgone, Quang tells Qui: “I am more than the eight years that I fought.” Poor Yella Rednecks shows us the flawed yet resilient people who were, in the final words of the play, “climbing mountains while the rest of them are sleeping.”

Recently, I asked my parents who their Congressional House Representative was in Anaheim. “Lou Correa,” said my mom. “He was at a rally the other week and he greeted us with kính chào quý vị (‘Welcome, everyone’).” A Mexican American politician, speaking Vietnamese publicly! We Asian Americans may have settled into the American fabric, but we’ve also stitched our own designs onto it.