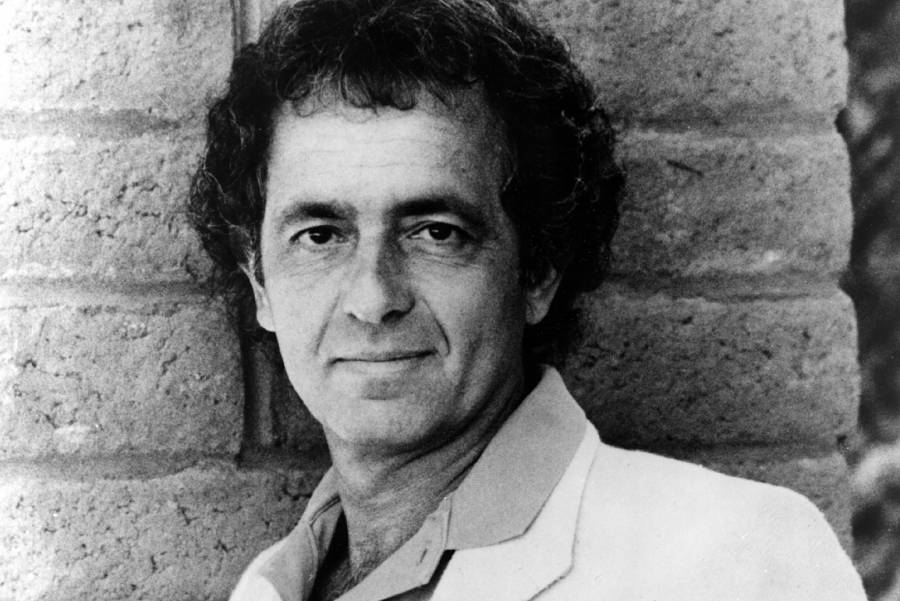

Playwright Mark Medoff, who won the Tony and the Olivier for his play Children of a Lessser God and who taught screenwriting and acting the University of New Mexico for 27 years, died on April 23 at the age of 79.

I first met Mark Medoff at an audition. It was at the Mark Taper Forum annex in Los Angeles, and I was reading for him and the director Gordon Davidson, for a role in Mark’s new play, Children of a Lesser God. Though I had read the play, I had not been given scenes to prepare and perform for the audition, which was highly unusual. Instead, in front of Mark and Gordon, I was given a lesson in American Sign Language by a professional teacher—a long paragraph which they observed me learning, and which I then had to speak and sign at the same time. I was nervous and self-conscious, but Mark made the moment light, even fun, with his self-deprecating but incisive and hilarious comments about his own struggles with the process.

He had met Phyllis Frelich, a Deaf actress, in Las Cruces, where he taught at New Mexico State University, and had become fascinated with the idea of writing a play about her relationship with her hearing husband, Bob Steinberg. He did, and they had performed the play at the university, and were now bringing it to Los Angeles for a second production. I had seen Mark’s play When You Comin’ Back, Red Ryder? six years before in New York, so I was aware of his ability to write very dark and abrasive characters, and I was struck by how gentle, funny, and even shy he was in person.

A few days later I was called back, this time to read a scene or two. I sat in the waiting area with a dozen other actors holding their scene pages, mostly women and men older than me, not the usual group of guys who looked exactly like me. At one point, April Webster, the casting director, came in out of the audition room, and rather abashedly announced that all the other actors could go on home—their roles had been cut from the play! Mark appeared behind her, apologized to all the bewildered actors, and thanked them for driving down there. After they left, he told me he felt terrible about it, but said, “We’ve made some changes! We’re still working!”

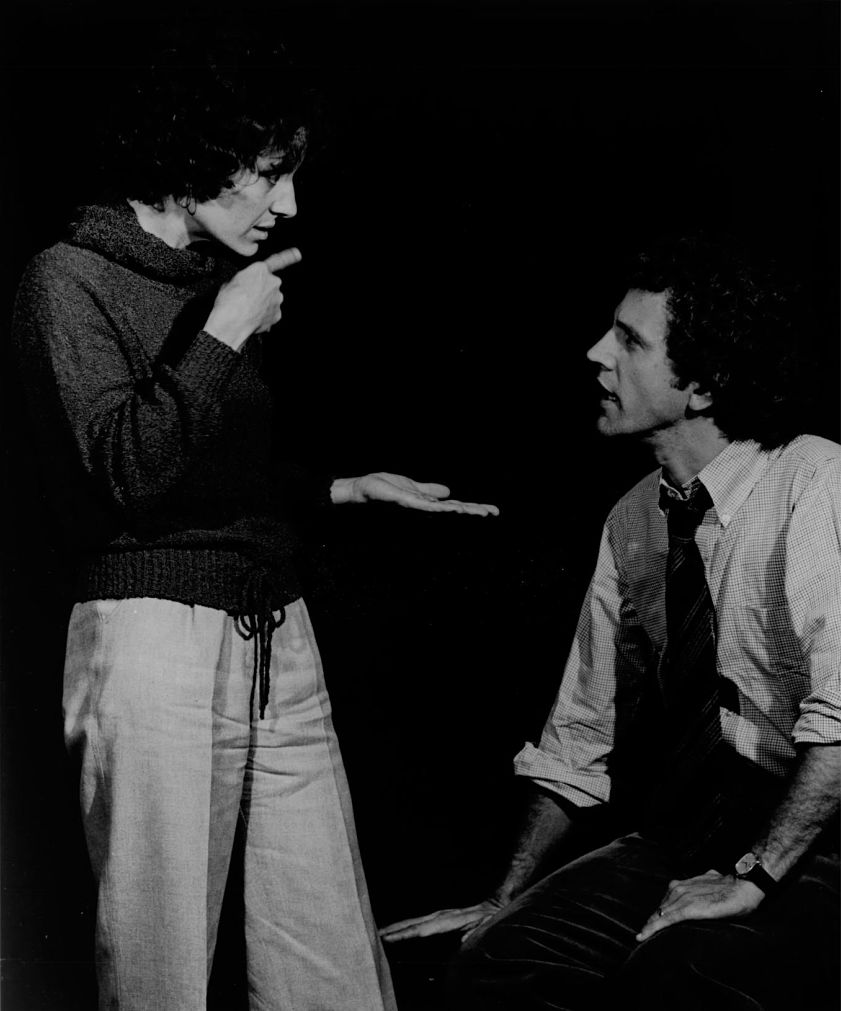

I was overjoyed to be offered the role of James Leeds, a speech therapist at a school for the Deaf, and we plunged into rehearsals. Phyllis Frelich was magnificent, saintly in her patience with me as I tried to learn the voluminous amount of words and the accompanying signs. Mark was nowhere to be seen. Our scripts contained only a first act, and the second act we had all read, and which Phyllis had performed in Las Cruces, was gone. Where was he? In an office on the second floor, hammering out an entirely new second act.

I had been in original plays before, where the playwrights would make changes and cuts on a daily basis after watching rehearsals. I had never known a writer to start from scratch on a new act with the clock ticking and the first preview looming in three weeks! Mark was a hero. He brought that second act to us, and while we tackled it in the rehearsal room, he stayed in the room, listening and writing, and new pages came in every day.

The play went well in L.A., and during the run we were told we would be going to New York in a few months to open on Broadway. Before leaving, the cast was called to meet with Gordon and Mark to talk about the play. Another first for me: a playwright who was open-minded enough to want to hear detailed reactions and ideas from the actors! The meeting went long, and the discussion was both emotional and pragmatic. When we reconvened in New York, Mark yet again added a brand new section to the second act, one which added a whole additional color to the drama. The audiences were ultimately taken on a very particular and soaring ride, one which moved their hearts in ways they hadn’t expected.

Even after all the accolades, awards, and success, Mark kept working on the original fascination he had with what Deafness is, how it affects both Deaf and hearing people, and how it creates a sense of separate but conjoined “worlds” that presented unexplored challenges and obstacles, as well as the possibility of liberation and discovery. It clearly opened portals to his own burgeoning imagination. His plays The Hands of its Enemy and Prymate, both written for Phyllis, continued the journey they had begun together.

The last time I saw Mark was, again, at the Mark Taper in L.A. This time it was at the memorial for Phyllis after her untimely death in 2014. Many of our Children cast and staff were there, and when Mark spoke, it was more than apparent how important she had been to him, as a muse and friend and colleague. His life’s work will be appreciated, I think, mostly through that lens: of his trying to understand and illuminate for others the “worlds” of not only the Deaf, but of people on all different paths who are attempting to bridge the gaps, to find the means of communication and connection to each other, to somehow improve humanity’s lot. I was fortunate and honored to be able to be close, even for a brief period, to Mark’s energetic and devoted commitment to that ideal.

John Rubinstein is an actor and director based in Los Angeles.