I have a confession you might find surprising: I don’t care about the Tony Awards. In fact, I don’t much care about Broadway in general. But wait! Hear me out before you close this window.

As someone who covers theatre on Broadway, Off-Broadway, Off-Off, and regionally, I regularly see around 150 shows a year (and yes, I’ve been known to get on a plane to see theatre). And if I had to choose between a new work by a young playwright playing Off-Broadway or a Broadway musical based on a movie, I will pick the play every time. I go where the great art is, and great art is everywhere. So why don’t the Tony Awards recognize that?

For those who don’t know, the Tonys recognize just Broadway productions. I dug a little deeper into what constitutes a Broadway production, and the answer I found was anything that plays in an eligible Broadway house, which is often defined as any venue in New York City with a seating capacity of more than 500 that stages primarily theatre (as opposed to concerts).

That seems cut and dried. Except it isn’t.

The rules are actually quite arbitrary and dependent on location. It’s not sufficient to say the Tonys honor commercial work, because commercial producers also work Off-Broadway, and four nonprofit companies have Tony-eligible Broadway houses. It’s not sufficient to simply say houses of 500 seats or more in NYC, because if that were the case such venues as the Brooklyn Academy of Music (top capacity: 2,109), Park Avenue Armory (top capacity: 1,500), and St. Ann’s Warehouse (top capacity: 700) might be considered eligible Broadway houses. If the rule is that only venues in Manhattan’s theatre district qualify (an area bounded roughly between 42nd Street and 54th Street, and 6th Avenue and 8th Avenue), then why is the Vivian Beaumont (owned by Lincoln Center and located on 66th Street) eligible as a Broadway house, while the Armory, also located on 66th Street but on the other side of Manhattan, is not?

A representative from the American Theatre Wing explains that it’s not just seats, it’s the labor agreement: Broadway contracts are the highest-paid in the business. In other words, Broadway is measured by money, not artistic quality.

The Tonys were first established in 1947, at a time when Broadway was the only theatre game in town. But times have changed since the 1940s, and they’ve changed since the late 1950s and ’60s, when Off-Broadway was born as an alternative to Broadway. Artists are no longer making theatre just in midtown, or just in Manhattan. They’re making theatre in Brooklyn, in Denver, all around the country. They’re making theatres in black boxes, backyards, and bars. An artist can make a living, and an impact, without ever setting foot on Broadway.

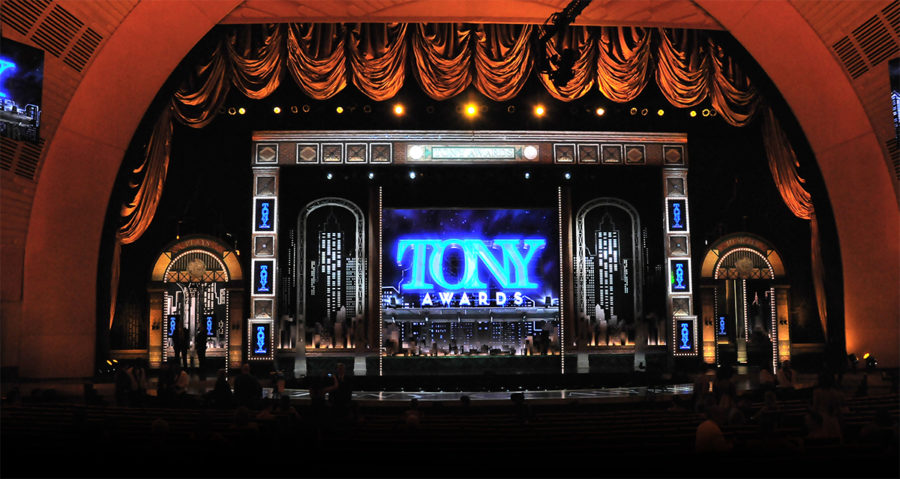

Yet the Tony qualifications remain unchanged. Millions of people around the country view these awards each year on CBS, which recognize only a tiny sliver of the nation’s theatrical ecosystem as “the best” of what the art form has to offer. If the Tonys are an indication of “the best” theatre in America, then what defines “the best” are big-budget works that can play to 500-plus people, almost invariably in a proscenium-style theatre (Circle in the Square notwithstanding). As anyone who has seen work in a black-box or site-specific setting can tell you, powerful works can happen in any kind of space, for audiences of 2 or audiences of 1,000. Great theatre occurs at any budget level, and in fact some works can have their impact diluted when scaled up to a larger house with the audience only facing one direction (I actually preferred the in-the-round staging of Hadestown at New York Theatre Workshop to its current Broadway configuration).

Imagine the Oscars only giving awards to big-budget studio films, and ignoring indies, documentaries, and shorts. That wouldn’t be a credible “best of” awards show, would it?

This is why I believe it’s high time for the Tonys to recognize Off-Broadway productions.

Off-Broadway is generally designated as New York theatres with 99 to 499 seats. Off-Broadway is where the great artists—and often shows—of our time are first presented. Before he was an Oscar winner, for instance Tarell Alvin McCraney—who finally made his overdue Broadway debut with Choir Boy this season—had been presented Off-Broadway multiple times. And 8 of the 34 shows that premiered this year on Broadway were transfers from Off-Broadway houses. So was Broadway’s hottest show, Hamilton.

Obviously the Tonys think Off-Broadway counts sometimes, since it placed Hedwig and the Angry Inch in the 2014 best revival of a musical category despite the musical never having been produced on Broadway, but because it first premiered Off-Broadway in 1998. It was a cult classic long before it won a Tony.

Increasingly what is considered the most artistically valuable work in the country isn’t even on Broadway (or doesn’t start there). In the last 20 years, 15 of the Pulitzer drama winners were works that debuted either Off Broadway or regionally (in 6 of those instances, the Pulitzer certainly helped propel the play to a Broadway run). But most of those plays won’t be nominated for the best play Tony. Jackie Sibblies Drury may have just won the Pulitzer (for Fairview), but because her play isn’t on Broadway, fewer people will be able to see it. And because she won’t appear on television for the Tony Awards, fewer people will know her name. If its Off-Broadway runs (at Soho Rep and Theatre for a New Audience) were eligible for Tonys, Drury wouldn’t have to go to Broadway at all to get the boost the nation’s most prestigious theatre award can confer.

It’s certainly not news that Broadway has a diversity problem. Out of this past season’s 34 productions, only 3 plays and 3 musicals were created by women (for a total of 18 percent), and only 3 works were created by authors of color. According to the Interval, What the Constitution Means to Me by Heidi Schreck is only the 12th play written by a woman to be nominated for a Best Play Tony. By contrast, around the country, 30 percent of all works produced this season are by female-identified authors (the number is better for new plays, of which 66 percent are female-authored). Artists of all backgrounds are creating work, but you wouldn’t know that from looking at the Great White Way.

Schreck had a long career as an actor and writer before making her Broadway debut, and she’s noticed the assumption that stories by women and people of color are “small,” while stories by white men are universal. “I’ve been in 200 plays in my lifetime and I think that 175 of them are by women,” says Schreck when we spoke earlier this spring. Male domination becomes a self-reinforcing cycle; because Broadway is a commercial realm where ticket sales are essential, and most Broadway shows are by men, people therefore “think that only plays by men make money.” It can lead to two-tier system, she points out, where “all of the uptown plays when I was coming up were by men and all of the downtown plays where I worked were by women.” In fact, Schreck never thought What the Constitution Means to Me, which began its life as an Off-Off-Broadway play, would ever get uptown.

Women and people of color also have to jump through more hoops to get to Broadway. White male playwrights such as Christopher Demos-Brown or Lucas Hnath can get produced on Broadway with some critical acclaim, but it took Pulitzer and Oscar wins for writers like Lynn Nottage or Tarell Alvin McCraney to make it to the Main Stem.

For playwrights, a Tony can mean not just commercial revenue for their show (though that doesn’t hurt). It also can mean an assured future for their work and a chance at career longevity as an artist. To the casual theatregoer, the phrase “Tony-winning” is a mark of quality. You can have a flop on Broadway that becomes a hit regionally, because of marketing. And the Tony telecast makes for a great marketing platform, as any Broadway producer will tell you.

Not every great theatre artist will get a Broadway production, and not every show is scalable to Broadway. This is where the Tonys could play a role: by shining a light on more artists making great work, not just the few lucky enough to catch the eye of Scott Rudin. Yes, there’s the annual Regional Tony. But if they want to truly represent the American theatre, the Tonys should find a way to recognize work at all budget levels, not just the most expensive. Perhaps the Tonys could take a page from the Oscars and allow any New York producer to submit their productions for Tony consideration. How would they get voted on? Since Off-Broadway productions already accommodate voters for the Obies, the Lucille Lortels, and the Drama Desk Awards, how much of a stretch would it be to add Tony voters to the mix? The idea was floated in a 2000 New York Times piece and the case for it feels even more urgent now.

There would be a lot of logistics to work out. Maybe in return for consideration, Off-Broadway producers would have to chip in to help fund the awards show, or since the American Theatre Wing adjudicates both the Tonys and the Obies, why not just combine those two voting pools. If the Tonys are essentially a giant ad for theatre, at least with Off-Broadway in the mix there would be more truth in advertising.

And while I know this isn’t going to happen this year or even next, if the Tonys are serious about showcasing the vibrancy of the art form, and why it’s necessary and relevant for today’s audiences, why not get our best minds together to figure out how these awards can be made better, more inclusive, less limited and limiting? The Tonys recognize some great artistry, and Broadway is the home of so many accomplished artists. But the American theatre is much richer than what the Tony broadcast on June 9 will show you. To quote a musical currently running on Broadway: “Country-a-changin’, got to change with it!”