As the U.S. theatre field goes through a much-needed and much-noted leadership turnover, it is also going through a programming transition, as new leaders put their unique stamp on casting, hiring, commissioning—in other words, who and what shows up on their stages.

Of course, not every transition is immediate or seamless, and filling these breaches are interim or acting leaders—and along with them, slates of plays they might claim some credit for as they mind the store. At Kentucky’s Actors Theatre of Lousville, for instance, artistic director Les Waters left the helm a full year ago, and his replacement, Robert Barry Fleming, was only recently announced. For this past season, then, the theatre’s programming has been spearheaded by two people, artistic producer Emily Tarquin and literary director Amy Wegener. It’s a particularly heavy lift, given that Actors Theatre essentially puts on two seasons in one, or rather one nested inside another: a mainstage slate that runs from September to April, plus the hugely influential Humana Festival of New American Plays, which is embedded in the larger season’s final months.

When asked whether this year’s Humana program, which ran March 1-April 7, should be thought of as their handiwork, Tarquin and Wegener were reluctant to claim it entirely as their own. As Tarquin put it, “As many theatre professionals will understand, in reality there is very rarely a single ‘stamp’—a central font of all ideas, artistic taste, and vision. The curation of the Humana Festival involves a ton of thoughtful conversation among staff across the artistic departments, and that ethos of sounding out multiple perspectives in the play selection process has remained a constant in our approach.” According to Wegener, who has been with the theatre since 1997, many of the decisions regarding this year’s Humana programming “were made while Les was still at the helm, and his leadership also continues with us. Our artistic team worked closely with him, and continues to function as a collective brain trust that works collaboratively with the whole organization.”

Fair enough. Theatre programming isn’t built in a day, or even a year. And certainly, having visited the Humana Fest three times now myself, the sense of continuity—those same three theatre spaces, the spirit of artistic risk inherent in essentially staging a whole season of new plays in just a few months, the free-flowing camaraderie (and bourbon) of the closing industry and press weekends—is perhaps as striking as any departures in style or personnel that can be clocked over the years.

But perhaps “continuity” is too static a word for Humana’s steady evolution. I definitely felt, as I watched this year’s four full-length shows and one short-play anthology over the festival’s closing weekend in April, that these new works were in conversation with past Humana offerings—and that the conversation had noticeably moved forward, in large part thanks to some vital new voices who’ve joined it.

For example, among the first plays I saw at Humana, in April 2003, was Theresa Rebeck and Alexandra Gersten-Vassilaros’s Omnium Gatherum, which conjured an otherworldly dinner-party debate about the so-called war on terror just as U.S. troops were barging into Baghdad. This April in the same theatre I watched Ismail Khalidi and Naomi Wallace’s earnest, affecting adaptation of Sinan Antoon’s novel The Corpse Washer, about an Iraqi family (barely) living through a series of U.S. or U.S.-backed incursions: first the Iran-Iraq war, then the first Gulf War, and finally the invasion of Iraq. How far we’d come, and not come, I thought, in the years between our comfy armchair debates about terrorism and the life-shattering impact of the wars launched in our name, wrenchingly embodied before our eyes.

I could also draw an instructive line from the Adam Rapp play I saw at Humana in 2011, The Edge of Our Bodies, which dealt in part with a young schoolgirl’s sexual experience with older men, to Lily Padilla’s blistering, heart-rending play this past season, How to Defend Yourself, about young women in the confounding crosshairs of collegiate rape culture. Or I could trace the bumpy road between Peter Sinn Nachtrieb’s garish tour of twisted Americana, BOB, also a 2011 offering, and this season’s ambitious race revue, Dave Harris’s Everybody Black. Or, not to belabor the point, I could construct a tripartite echo chamber of haunting theatrical legerdemain containing Rinne Groff’s magic-themed Orange Lemon Egg Canary (2003), Anne Washburn’s Philip K. Dickian mindfuck A Devil at Noon (2011), and this year’s paranormal parlor stunt from Lucas Hnath, The Thin Place. The more things stay the same, it seems, the more they change (and vice versa).

Did Tarquin and Wegener feel any of these resonances, either over the years or within the offerings at this year’s festival? I wondered.

“Any time you experience works of art as a collection,” said Tarquin, “you can’t help but draw parallels, perceive patterns, and take away themes.” True that. For her part, Wegener noted that this year’s festival featured “plays that really revel in their theatricality—that make the most of unfolding live in the room with the audience,” and that “what resonates with us is what’s resonating in our communities, for the artists, and in our industry.”

That said, Wegner added that the “curatorial impulse has been one of contrast, of celebrating stories and styles that feel different from one another.”

Mission accomplished with this year’s four full-lengths (previous years have featured as many five or six such offerings; Tarquin explained that the number reflects “a balancing act of fully producing the stories we want to share, production budgets, and how we can best support and serve each play’s development process”). While The Corpse Washer contains its share of time-splicing and magical realism, as dead friends and family hang around and speak to Jawad, the young embalmer of the title, it mostly follows a straightforward expository theatrical style. The fluid staging by Mark Brokaw, and a richly appealing cast, helped show the play in its best light.

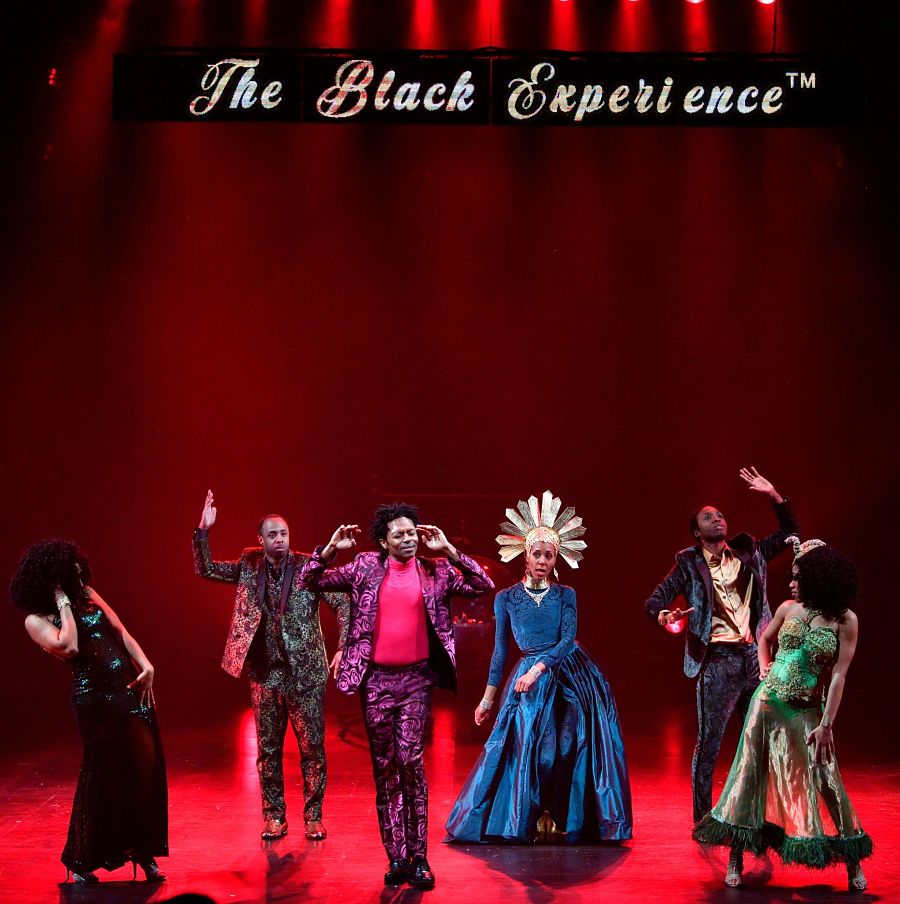

Harris’s Everybody Black, meanwhile, is a sparkling and self-assured entry in a new canon of African American meta-theatre that is interrogating the white gaze on its own unapologetically Black terms, and often having a blast doing it. Like Jordan E. Cooper’s Ain’t No Mo’, Harris’s anthology format owes some debt to George C. Wolfe’s The Colored Museum, with its fat-target call-outs of leering Black sitcoms, clueless hoteps, and “official” Black historiography, while its onion-layered form and relentless self-interrogation recalls the work of Jackie Sibblies Drury or Branden Jacobs-Jenkins (who gets his own in-joke call-out).

Hnath’s The Thin Place has the playwright’s signature mix of bluntness and indirection, of disarmingly conversational dialogue and roiling subtext. It follows a young woman (played with glistening opacity by Emily Cass McDonnell) whose apparent psychic abilities unsettle and ultimately unseat those of a professional adept. The play’s climax involves some eerie, even spine-tingling stage trickery, though to me the play’s center felt like a free-ranging party scene in which wine and candor lead a quartet of tenuously related folks to some unexpected, even dangerous places. Directed without frills by Waters, it represents Hnath at his most gnomic and impish.

The play that hit me hardest (and I wasn’t alone, based on conversations with other theatregoers there and since) was Padilla’s How to Defend Yourself. With its sexual frankness, emotional rawness, and moral fervor about the bodies and souls of young women, it bears favorable comparison to the likes of Ruby Rae Spiegel’s Dry Land, Sarah DeLappe’s The Wolves, Ming Peiffer’s Usual Girls, and Clare Barron’s Dance Nation. Following the ostensible self-defense workshops attended by five sorority girls and two frat boys, Padilla’s play ranges widely and unflinchingly over familiar youthful territory—desire, consent, peer pressure, social media bullying and one-upmanship, self-harm—and makes these hot-button themes pop and sting with fresh urgency. Padilla (whose pronouns are they/them) doesn’t shy away from broad gestures, but they also display fine attention to detail. Though the focus is mostly on the shifting alliances between and among the genders, Padilla makes subtle but indelible reference to racial difference as well: Near the top of the play, when two white girls barge into a gym where a Latina and an Iranian girl are talking, they instinctively hesitate and check in with each other, “Um, is this the right…?”

I also caught the anthology show, We Have Come to Believe, which as always proved a diverting if slightly wearying exercise in showcasing Actors Theatre’s eager acting apprentice company. Purportedly themed around the subject of religions and cults, it mixed droll sketch-comedy twists and baffling theatre-game-like gambits. The apprentices also made themselves seen and heard memorably before each performance, delivering curtain speeches that went beyond the usual cellphone-and-candy-wrapper warning to voice the festival’s mission, concluding thus: “Actors Theatre is working to become a brave space for all and appreciates your support in that goal. Listen, learn, and engage in this experience together. Thank you for showing up.”

I asked Tarquin (whose pronouns are they/them) about this, and they told me that it was a conversation with Padilla that “propelled a lot of the language” of that core-values statement. “We learned that people were really listening to that message,” Tarquin said, “and many took time to contribute thoughtful feedback and suggestions that we will continue to learn from.”

The listening and learning continues. The closing weekend of the festival featured the presentation of the Steinberg/ATCA Awards, which went to Lauren Yee’s Cambodian Rock Band, with finalists including Jen Silverman‘s Witch and Noah Haidle’s Birthday Candles. Jim Steinberg, a trustee of the Steinberg Charitable Trust and son of the new-play awards’ namesakes, cultural philanthropists Harold and Mimi Steinberg, opened the awards ceremony with a speech about the “sea change” the field is going through. Giving a thumbnail history of American theatre since the Little Theatre movement of 100 years ago, Steinberg hailed “the emergence of a new generation of leaders: young, smart, aggressive, and often more political…This is the sea change that we’re talking about, and these are our new boat rockers. This is another new beginning. And we need to acknowledge this, and we need to support them. I don’t know where this new generation of leaders will take us. But I do know we’re all anxious, interested, and very excited to see.”