“We are trying to do a fun thing in a hard way,” says a character named Cora, with a wide-eyed look of impatience, and members of the audience laugh in recognition. The 10-year-old character, the eldest of three kids, is balking at the effort necessary for the activity her brother and friend have cooked up in their basement: a simulated night in the woods, conjured with the aid of a sophisticated mobile app, objects lying around the basement (hand warmers, a Christmas tree color wheel), and some imagination.

It’s that last element that eludes Cora, at least for the moment. Imagination is also the thing that promises to make the kids’ evening, and the play they’re in, a magical experience. The play they’re in is called The Ghost of Splinter Cove, but it’s only half a sort of theatrical double feature called the Second Story Project, a first-of-its-kind joint commission by Children’s Theatre of Charlotte and Actor’s Theatre of Charlotte. It comprises two plays penned by Steven Dietz, crafted for the two theatres’ different audiences: Splinter Cove is the family-friendly show at Children’s Theatre, following the exploits of Cora, brother Nate, 8, and 9-year-old Sydney, while The Great Beyond, performed at Actor’s Theatre of Charlotte, explores what the parents are up to on the house’s main floor on the same night. It’s a concept that recalls such Alan Ayckbourn projects as the contemporaneous diptych House and Garden or the trilogy The Norman Conquests; each play stands alone, but they also play well together. In the case of the Dietz works, some pre-recorded dialogue allowed a handful of lines to appear in both plays, and some design elements (especially the lighting and sound for The Great Beyond at Actor’s Theatre) give a nod to what’s happening in the alternate piece.

The two theatre organizations in North Carolina’s Queen City staged the plays with overlapping runs that wrapped up in the first week of April, which means I had the chance to catch them both on the same day. It’s rare to see two theatre companies in one town come together in quite this way. The result showcased a component of theatre many in the field hold up as unique: its ability to unite people. Coming together and family were also, perhaps not coincidentally, among the themes of the plays. This project brought together theatregoers of different generations in different parts of the city (CTC in NoDa, the city’s arts district, and ATC in the historic Myers Park neighborhood), fostering something akin to an extended family among Charlotte’s theatre workers and theatre audiences. It seemed only fitting that a pair of plays about the completeness of family, a pair of plays that highlight the sense of family that exists even when its members are apart, should resonate with the process of their making.

It doesn’t hurt that both were presented in kid- and community-oriented spaces: Children’s Theatre operates out of ImaginOn: The Joe & Joan Martin Center, a sprawling complex that also houses a branch of the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library, which shares a couple of staffers with the theatre. And Actor’s Theatre, resident theatre of Queens University of Charlotte, performs in the campus’s Hadley Theater, located in Myers Park Traditional Elementary, part of the local public school system.

While the piece for young audiences is lighter in tone, both plays, as their titles imply, grapple with death. In The Great Beyond, Monica—Nate and Cora’s mom—has recently lost her father, who owned the house where the characters in each play congregate. The passing of her dad has reunited Monica with her ex-husband, Rex, and her sister, Emily, and has introduced Rex and Monica to Emily’s partner, Rene (Sydney’s mother). While the kids in The Ghost of Splinter Cove end up navigating their family mysteries through play, the grown-ups in The Great Beyond are on the main floor sorting out their issues, dealing with each other’s tensions, regrets, and hang-ups, a process that leads them to hold a séance. (Early in Splinter Cove, before the kids’ activity gets going in earnest, Cora laments, “It’s been 20 minutes. How much ‘adult time’ do they need?”)

The kids and the adults occupy different worlds—as Dietz wrote in the playwright’s note that appeared in both shows’ programs, “Childhood and adulthood are different continents, separated by a sea of time”—yet both groups of characters have more in common than they know, as both invoke something ethereal in wrestling with complex issues. (One impetus for the plays’ premise, Dietz told The Charlotte Observer, came to him when he was “thinking about something to do with a séance, and I wondered, ‘What if the adults conducted one and accidentally sent someone into the other world downstairs?’”) The characters within each play, and between the two plays, fortify the bond with each other along the way.

This sense of camaraderie was made all the more palpable by the communal experience of seeing two plays at theatres in different locations and realizing that many of the attendees were at the same pair of performances. Of course, not everyone taking in both shows got to see them on the same day—there were only three such Saturdays when that itinerary was doable—but for me it heightened the experience. During his pre-performance speech, Actor’s Theatre executive director Chip Decker, who helmed The Great Beyond, asked audience members to raise their hand if they’d gone to the other play that afternoon. The majority of hands went up.

Unity was baked into the project from the start. Between the afternoon and evening performances, Decker and Children’s Theatre artistic director Adam Burke told me that they’ve met regularly since Burke came to Charlotte in 2013 to take the position at Children’s Theatre and reached out to various theatre leaders in town. At one of these meetings in 2015 they joked that their respective companies should do something together.

“We laughed about it,” Decker recalled, referencing the stark difference in programming between his company and Burke’s, “because it’s like, ‘Yeah, I’m gonna come over there and drop a bunch of F-bombs on your stage.’”

Then it dawned on them that the idea wasn’t ridiculous at all. Decker, who’s worked at ATC in various capacities since 1996, said he realized that Burke’s audiences “are my future audiences. This is a no-brainer when you get right down to it.” So the two artistic leaders went back and forth, brainstorming what a collaboration might look like, eventually landing on the two-commission idea.

To secure funds for the commission, CTC managing director Linda Reynolds, at the time the company’s director of advancement, sought out “a philanthropic partner who shared and encouraged our experimentation and learning along the way.” Reynolds found that partner in Charlie Elberson, trustee of the Reemprise Fund, a Foundation for the Carolinas initiative that supports nonprofits in risky, “potentially game-changing” ventures. Elberson said he was enthusiastic about the concept from the first conversation he had with Reynolds and Bruke about it. “I had recently been reading about the ability of performing arts to create and drive empathy in audiences, especially among children and young people,” Elberson said. “The potential for families to share the experience, bridging each other’s perspectives in a manner never before attempted, was inspiring and certainly seemed worthy of our support.”

The Reemprise Fund contributed $171,000 toward commissioning, workshopping, and production expenses for Splinter Cove, including an in-depth research component, suggested by Elberson and conducted by a group of theatre and psychology professors at UNC: Beth Murray, Jeanmarie Higgins (now at Penn State), and Lori Van Wallendael. Though the funds were earmarked for Splinter Cove, Decker noted that those resources allowed CTC to provide workshopping and non-production support for The Great Beyond. The work on the Actor’s Theatre side was also made possible by a $10,000 grant from the National New Play Network.

Once funding was lined up, the two organizations needed to choose a playwright, seeking an artist comfortable writing for both general and family audiences. Steven Dietz’s name dawned on them in 2015, when CTC staged Dietz’s Jackie and Me; Actor’s Theatre had done Dietz’s Becky’s New Car and Yankee Tavern. When they reached out, Dietz said he “just jumped at” the prospect. He had questions, though: When he gets a commission, he makes a point to “really drill down with an artistic director and make sure there isn’t a play they secretly hope I write.” Dietz was pleasantly surprised to learn that Decker and Burke truly wanted to leave possibilities open. “I didn’t really believe them,” Dietz said with a laugh. But they were sincere, and Dietz said he found the flexibility both exhilarating and frightening.

Dietz made trips to Charlotte to get to know the two companies better—though they’d each presented his work, he hadn’t seen a show at either theatre—and began writing, starting with Splinter Cove, and recommended as director for that play his former UT Austin student Courtney Sale, now artistic director of Seattle Children’s Theatre. (Incidentally, STC was responsible for Dietz’s only previous TYA commission, Still Life With Iris, which received its world premiere there more than two decades ago.) For Sale, who joined for the first workshop and remained with the piece through the Charlotte production, the project is all about bringing people together.

“When we are doing our work well,” she said, “we ask young audiences to connect story rather than collect story. For young people to know that across town in Charlotte a companion piece was occurring was as if we were letting the entire audience in on a big-scale secret—that truth drove the mystery and longing in both plays.”

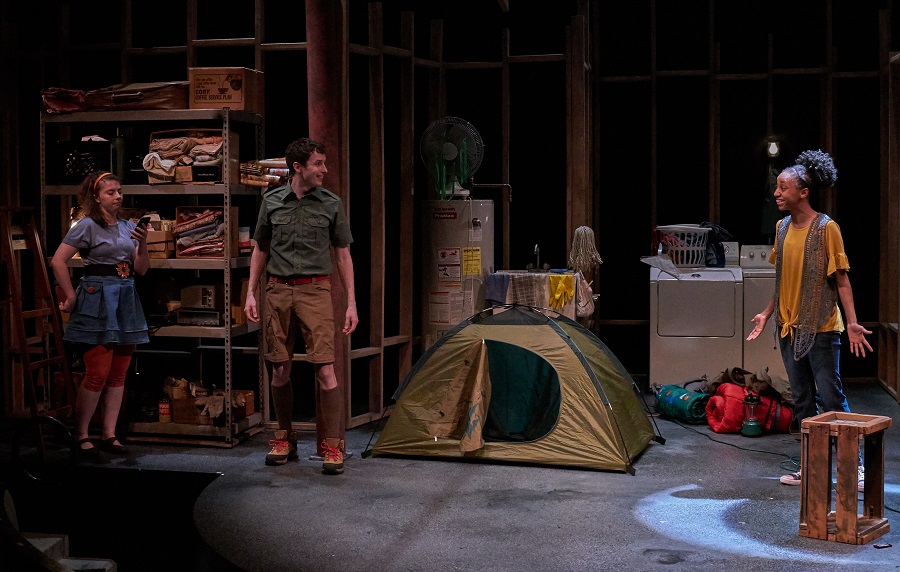

A similar sense of collaboration applied to the design team. For scheduling and other logistical reasons it wasn’t feasible to have 100 percent overlap for the designers of the two shows, but sound designer and composer Rob Witmer and costume designer Magda Guichard worked on both, and the other members of the teams were in conversation with each other throughout the process. (For The Ghost of Splinter Cove, Katie Pohlheber served as stage manager, scenic design was by Anita J. Tripathi, and lighting was by Fritz Bennett; the cast included Carman Myrick, Chester Shepherd, Kayla Simone Ferguson, Arjun Pande, and Mike Dooly. For The Great Beyond, Kathryn Harding served as stage manager, scenic design was by Evan Kinsley, lighting was by Hallie Gray, and props were by Carrie Cranford; the cast included Tonya Bludsworth, Scott Tynes-Miller, Robin Tynes-Miller, and Tania Kelley.)

For those interested in following up on this kind of joint effort, a number of people involved in the Second Story Project have some helpful advice. “For future companies, I would say that utilizing the same design team (with lots of careful tech planning!) makes for a dynamic and deep experience,” said Sale. “It’s also an opportunity that is yearning for marketing, development, and education areas to engage in bold collaboration and shared learning across theatres—something we don’t often see in the field.”

CTC’s Reynolds stressed the importance of finding funders like Elberson at the Reemprise Fund, a backer “who gets that the creative process for something this unique can be messy; needs, challenges, and opportunities will shift along the way, but the rewards, learnings, and possibilities are an amazing outcome.” Added Elberson, “I would recommend to any funder that this dual-audience approach provides rich opportunities for optimizing the impact of a performing arts investment. As with Second Story, it opens up new opportunities for audience engagement programming in ways that allow different generations to see from one another’s points of view.” That’s one thing theatre, like family, can do.