Japan comprises a people, place, and culture that both glance backward to celebrate and preserve a rich past, while simultaneously seeking ways to innovate and blaze forward into the future—much like a god or demon in kabuki theatre who can see in all directions while standing still.

This dynamic can be seen in a striking campaign by Tokyo Tokyo Old meets New, a government initiative branding Tokyo as a city “where unique traditions and advanced culture coexist and come together.” The ads depict a woodblock print of a geisha in contrast with an image of the humanoid holographic singer, Hatsune Miku, and a Shochiku kabuki actor alongside Robi, the interactive robotic companion.

This paradox of two distinctly different worlds comfortably coexisting is so deeply imbued in the culture that it becomes obvious to anyone who’s ever visited Japan—perhaps even more than to the Japanese themselves, as this juxtaposition is such a part of daily life it may go unnoticed. History and tradition are glorified and honored, while the desire to rack up new achievements is so strong that many from the Land of the Rising Sun—so called because the dawn comes so early, Japan is literally in the future compared to most of the world—are so overworked they fall asleep in transit or at work.

Though the nation boasts the most centenarians and oldest human beings overall, it also has a high suicide rate and a rapidly declining population due to a low birth rate. Despite these challenges, the Japanese live by the code of gaman—a term meaning “enduring the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity,” commonly simplified as “perseverance.”

The nation’s paradoxical old/new dynamic is especially true in Japanese theatre, where centuries-old practices are still performed by both traditional and contemporary companies, while cutting-edge technology and pop culture have become regular players as well—and the two often intersect.

Understanding Japanese theatre today is a way to understand Japanese culture itself. A multitude of layers are revealed, like a lotus unfurling its petals one by one, or a Pandora’s Box exploding with so many contradictions and dimensions that it can feel overwhelming at times. To get as complete a reading as possible of the pulse of Japan’s theatre scene, I visited the archipelago nation in February 2019 with my partner and translator/coordinator. In two weeks we conducted more than 30 interviews and meetings and saw 20-plus shows in six cities (Tokyo, Yokohama, Kyoto, Hyogo, Osaka, and Shizuoka). We also attended TPAM, an annual performing arts networking and cultural exchange conference that also hosts TPAM Direction, a curated international platform of diverse contemporary performance offerings, particularly from Asia, and TPAM Fringe, an open-call outlet for theatrical groups from Japan and elsewhere to showcase work to both locals and visiting presenters.

A few aspects unique to Japanese theatre are worth mentioning up front. First, public or government funding was not really a factor until the foundation of the Japan Arts Fund in 1990. That seismic shift, as well as 1998 legislation “to promote specific nonprofit activities,” a.k.a. the NPO Law, combined to dramatically expand support for the performing arts. The Japan Foundation, the Agency for Cultural Affairs, and more recently the Asia Center (created in 2014) have also been key players in promoting cultural exchange on a local, regional, and global scale. These developments are very recent compared to long-established nonprofit or subsidized theatre culture in the West. That means that commercial theatre in Japan still often takes the lead—though in Japan it doesn’t function quite the same as in the West. It’s more like a hybrid of the two sectors. There’s an awareness of the bottom line, yes, but also a mission of community outreach, and equal attention to upholding history and to forging dynamic visions for the future.

Second, there is kaisha, which refers both to the companies that employ around 40 percent of the Japanese workforce for a lifetime and to the lifelong “company man” ethos this practice embodies. In Japan, goals and ambitions are typically thought of in terms of “we” rather than “I”; politeness, humility, respect, and consideration are cardinal virtues; and the good of the group is prioritized over individual success.

Third, Japanese theatre tends to be character-driven rather than text-centric, with a focus on physical attributes—not that words are unimportant, as many have been preserved for centuries and are still performed faithfully. Fourth and finally, the Japanese have a penchant for perfectionism, which is as clear in their performing arts as in everything else they do.

While it is as impossible to give a comprehensive overview of the nation’s theatre as it would be to summarize its entire culture in a few pages, here are some of our discoveries about the complex, fascinating, and diverse world of contemporary Japanese performing arts.

Traditions Transforming

Three of the nation’s oldest theatrical art forms—noh, kabuki, and bunraku—thrive in present-day Japan. The government encourages cultural preservation, but it’s not a stale museum approach to these live arts: Alongside lineage holders proudly maintaining the traditions for generations are spirited visionaries continually emerging to adapt these styles to the tastes of modern audiences, catapulting the ancient arts into the new millennium with no end in sight.

Noh and kyogen, its comic version, are the earliest and oldest continuously practiced forms of theatre. They also laid the foundation for kabuki and bunraku puppet theatre, both of which use some of the noh repertoire of about 250 plays (one-third of them by Zeami, noh’s 14th-century creator). It’s also the basis for most Japanese performing arts, even contemporary musicals and plays. Noh and kabuki are highly stylized and rooted in archetypes, much like commedia dell’arte, which is one reason they’ve been easy to pass down through the centuries. Times and circumstances may change, but basic human desires and emotions rarely do.

That’s why the art form has survived, contemporary noh actor Kanji Shimizu believes. Shimizu, who trained under late masters at the Kanze School, both performs the classical noh repertoire and helps create new noh plays with fresh relevance. “The issues involving humanity in modern society are different from those in medieval times,” he says. “I believe it is necessary that we tackle these issues by writing contemporary noh plays.” Holy Mother in Nagasaki, for instance, is about the U.S. use of the atomic bomb and its many nameless victims, and At Jacob’s Well, a collaboration with an Austrian writer, addresses the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Noh may soon become even more known on the world stage. Mansai Nomura, a third-generation kyogen master (he’s the son of Living National Treasure Mansaku Nomura and grandson of the late Manzo Nomura IV), has been chosen for the coveted role of orchestrating the opening and closing ceremonies at the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Nomura, who’s artistic director of Setagaya Public Theatre in Tokyo, will now be responsible for, as honorary Olympics president Fujio Mitarai puts it, “implementing the spirit and vision of the Tokyo 2020 Games.” Nomura represents an ideal fusion of old and new, having appeared on a Japanese children’s show to promote kyogen and other ancient Japanese arts.

Bunraku, a form of puppet theatre, has also gone through various incarnations over the years. The traditional form, kept alive by the Bunraku Association, requires three puppeteers per puppet. Gloriously crafted and adorned, they can express extraordinary subtleties of human emotions. Koryu Nishikawa V is the fifth-generation master of Hachioji Kuruma Ningyo Puppet Theater, a 170-year-old style inspired by bunraku which translates to “puppets on wheels,” in reference to the form’s single puppeteer, positioned on a wheeled dolly for more mobility. Nishikawa, who brought his troupe to the Japan Society in the U.S. in early 2019, constantly seeks new ways to engage new audiences and refresh the tradition: He demonstrates the art at kindergartens and elementary schools, tours extensively, and collaborates with an American puppeteer, Tom Lee.

Alongside these traditional practices is a more recent innovation, butoh, a form of avant-garde dance theatre born from the same Japanese post-WWII counterculture movement that birthed angura (underground) theatre. Influenced by Neo-Dadaism, French mime and literature, ballet, gymnastics, and modern dance, butoh embraces the grotesque and surreal, and still thrives at such theatres as Kyoto Butoh-kan and at the annual New York Butoh Institute International Festival, which gathers practitioners from around the world.

Japanese stages are also filled with various hybrid forms of contemporary dance, which thanks in part to its nonverbal expression is a natural for international touring. Some outstanding examples we encountered during TPAM Direction and Fringe: the striking visuals of the high-tech, high-concept company Nibroll, led by choreographer/playwright Mikuni Yanaihara, in collaboration with video/lighting artist Keisuke Takahashi and composer/musician SKANK; the comedic physical theatre, dance, and mime troupe Company Derashinera, helmed by Shuji Onodera; and Co. Un Yamada, whose Ikinone, inspired by a 700-year-old flower festival, evoked Pina Bausch’s Rite of Spring.

Perhaps the most widely recognized Japanese performance form is kabuki. The tradition is in excellent hands with Ippei Noma, executive officer of Shochiku Co., Ltd. Founded in 1895, Shochiku has always been among Japan’s foremost cultural innovators, from stage presentations (including the earliest Shakespeare and musical translations) to film, television, and multimedia explorations, as well as being the official exclusive promoter of kabuki in Japan. All this may seem a heavy weight to shoulder, but Noma, equal parts traditionalist and trailblazer, is unafraid to take risks with his work in the service of this 400-year-old dramatic art.

Noma believes that classical kabuki is Japan’s equivalent to opera, and as a theatregoer I concur. Not only does the experience thrill and engage all the senses in “the world of extraordinary” immediately upon entering the theatre; as in opera, many of the stories are tragic yet transfixing. A typical day at the kabuki theatre features two distinct matinee and evening programs of three pieces each (two text-based and one dance), spanning about four hours with breaks in between. During these intermissions, elegant audiences take out their Makunouchi (“between acts”) bento boxes, a tradition dating back to the Edo period (1603-1898). Noma explained the ubiquitous kabuki shout of “Yoooo!,” followed by the thump of a drum: In the absence of a conductor, it’s a lead-in cue for the background music.

Shochiku has also looked to the future of the form. Thanks to a series of serendipitous events, beginning with the reconstruction of the Kabukiza Theatre and Kabukiza Tower in Ginza, Tokyo, in 2013, when Japan was in a financial and national crisis, the company developed a relationship with one of the new building’s tenants, the internet-based entertainment enterprise Dwango Co., Ltd. Dwango urged Noma to explore more radical approaches following the success of their kabuki adaptation of the popular manga/anime One Piece. This in turn sparked the conception of cho (extreme/super) kabuki, integrating 3-D projections and video mapping into kabuki performances, and casting Dwango’s biggest attraction, Hatsune Miku—a teal-pigtailed singing virtual humanoid who sells out arenas all over the world—alongside kabuki superstar Shido Nakamura.

Other forms of Japanese theatre follow theatrical templates more familiar to Western audiences. Indeed Gekidan Shiki (founded in 1953 and named for the four seasons) is best known for its joyous renditions of licensed Western musicals, including the works of Disney and Andrew Lloyd Webber. Shiki boasts a massive full-time employee roster of artists, technicians, and administrators and eight theatres across Japan. Cats and The Lion King are its ongoing staples, but don’t expect Hamilton there any time soon (“It’s too American for our audiences—not universal enough,” remarks president and CEO Chiyoki Yoshida). Likewise Toho Co., Ltd., which was established in 1932 by Ichizo Kobayashi, stages American musicals as part of an entertainment empire that includes film, anime, video games, and its most famous property, Godzilla.

Takarazuka Revue, now 105 years old, stages lavish shows with production values rivaling Broadway, Las Vegas, or the Rockettes. But the revues put on by this all-female company, in which women also perform the male roles (in direct contrast to the still all-male kabuki) are unlike any other musical theatre you’re likely to see. The closest comparison might be to such Western artists as David Bowie or Prince—flawless technicians who could seamlessly execute different styles, genres, and gender expressions, and who were always reinventing themselves.

Pop Goes the Cutting Edge

It probably comes as no surprise, given the strong association of Japan with modern technology, that today’s Japanese theatremakers are keen to explore tech’s endless possibilities. Equally exciting, though, are possibilities afforded by one of Japan’s other popular exports: its pop culture. The biggest and most pervasive boom involves stage incarnations of anime and manga, dubbed “2.5D entertainment.” These are such a big part of Japanese culture it’s shocking that this crossover didn’t occur sooner. (See related story here.)

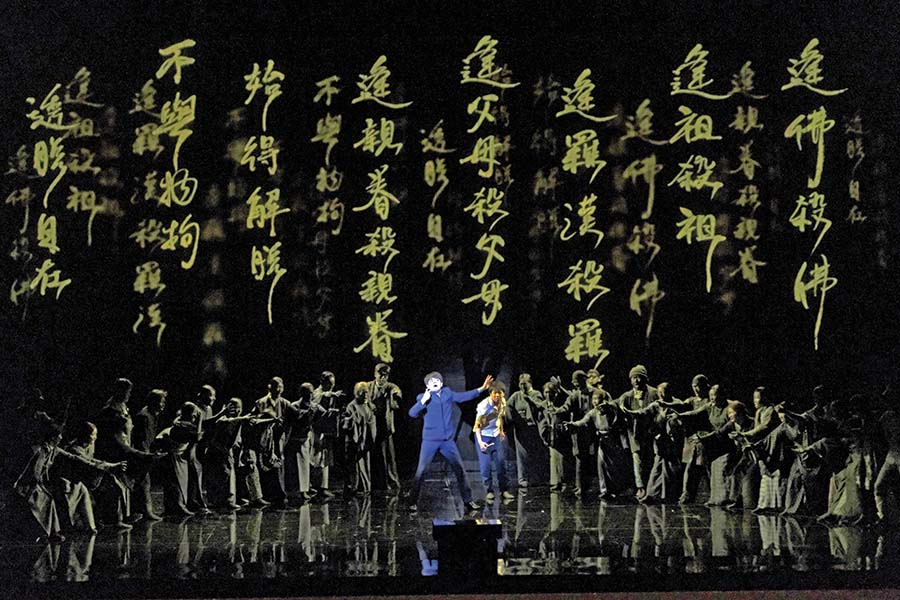

Some theatre innovation is architectural. TBS (Tokyo Broadcasting System) broke new ground with a 360-degree revolving theatre, IHI Stage Around Tokyo, modeled after Holland’s Theater Hangaar. The new 1,300-seat venue was built on reclaimed land in the Koto Ward Toyosu Wharf district atop Tokyo Bay, as there was simply no room at a reasonable cost in central Tokyo. The theatre’s debut show, Seven Souls in the Skull Castle—an amalgam of Shakespearean drama, rock opera, comedy, and an epic samurai film—is a repertory favorite written by Kazuki Nakashima for Gekidan Shinkansen, a punk-rock theatre troupe formed in the 1980s. With five rotating casts featuring renowned stars, Seven Souls ran for an unprecedented 15 months at IHI Stage Around Tokyo. Next is the theatre’s first Western musical, a 360-degree West Side Story. (Sadly the theatre’s lease is up in 2020, leaving the venue’s future uncertain.)

A first-time visitor craving a buffet of Japanese culture (with some Western flair) might try KEREN, playing from late February-August 2019 at Cool Japan Park Osaka. The word keren refers to the gimmicks or “tricks” used in kabuki to delight and impress. Directed and written by Tetsuo Takahira, KEREN takes these stage tricks to the extreme with outstanding visual art by a Canadian multimedia studio, Moment Factory, and some Broadway glitz in the choreography department, provided by the legendary Baayork Lee, renowned tap star HIDEBOH, and chanbara (sword fighting) by Kill Bill fight choreographer Tetsuro Shimaguchi. In an explosively energetic spectacle, audiences get treated to a winking parade of Japanese stereotypes: salarymen chasing vixens in schoolgirl outfits, conveyor belt sushi, dancing Toto bidet toilets, ghosts from ancient folklore, and thrilling yakuza battles.

Western musicals aren’t the only imports beloved by Japanese theatremakers and audiences. Recently HoriPro presented the David Hare version of Chekhov’s Platonov, brilliantly acted and breathtakingly directed by Shintaro Mori. Satoshi Miyagi’s exquisite vision of Antigone, slated for New York City’s Park Avenue Armory in September, sets the Greek masterpiece in a large river and stirs in contemporary noh, Indonesian shadow play, and Buddhist philosophy.

Shakespeare is also enormously popular, with Japan second only to the U.K. in the number of productions of the Bard’s works. Macbeth seems to be the favorite, perhaps due to the humility-favoring society seeing it as a cautionary tale. The variations are legion: There’s Macbeth by SYAKE-speare, an all-female contemporary noh company; Gekidan Shinkansen’s Metal Macbeth at IHI Stage Around; and Ashita no Ma-Joe (a.k.a. Rocky Macbeth), performing at New York’s Japan Society May 15-18. And there was Ninagawa Macbeth, an astonishing production that adorned stages worldwide with cherry blossoms, a symbol of impermanence, and took its final bow at Lincoln Center in the summer of 2018, closing the book for its acclaimed late auteur, Yukio Ninagawa.

A lineage and kaisha mindset is so prevalent in Japan that the torch-passing is almost unconscious. Visionary directors like Toshiki Okada of the company chelfitsch followed in the footsteps of Oriza Hirata’s contemporary colloquial theatre, but made it his own by contrasting naturalistic words with aloof or absurd gestures, and focusing on concerns of a more global society. Carrying the flame for the still active directing legend Tadashi Suzuki are Satoshi Miyagi, as artistic director of Shizuoka Performing Arts Center (SPAC), a role Suzuki originated, and Anne Bogart with her New York-based SITI Company. Both artistic heirs to the SCOT/Suzuki lineage have carved out their own creative domains.

Meanwhile the prolific powerhouse director Amon Miyamoto has staged more than 120 productions, including plays and operas. But his heart belongs to musicals. Though his first production in America, I Got Merman, had the misfortune of opening the week of 9/11, it led to his directing the 2004 Broadway revival of Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman’s Pacific Overtures; he was the first director from Asia to helm it. His recent Japanese original musical, Ikiru (“to live”), based on the famed Akira Kurosawa film and produced by HoriPro, attracted multigenerational audiences, raising hopes for its fortunes abroad. He is also working on a top-secret Broadway-bound musical with U.S.-based Gorgeous Entertainment.

Significant female contributors include the aforementioned Mikuni Yanaihara (represented by female-driven producers precog co., Ltd., who also look after Okada and others); director Erica Ogawa; and Tokyo-born, Brooklyn-based translator/director/playwright Aya Ogawa, who in early 2019 had her play The Nosebleed at New York City’s Under the Radar festival, and recently directed Kristine Haruna Lee’s Suicide Forest, inspired by the real-life Aokigahara Forest near Mt. Fuji, at Bushwick Starr in Brooklyn.

Indeed I would be remiss if I didn’t mention here the enthusiastic efforts of two New York angels: Yoko Shioya, performing arts director of Japan Society, who acts as a sort of fairy godmother to Japanese artists of every genre, often giving them their U.S. debut, and Kumiko Yoshii of Gorgeous Entertainment, who acts in a similar role for the commercial sector. Both are regular game-changers.

East, West, and in Between

The West is no longer the only option for Japanese companies looking to tour, create, and collaborate, as there is more cultural understanding, interest, and funding available than ever before among Asian nations, including South Korea, China, and countries in Southeast Asia. This cross-pollination is a focus of organizations such as the Japan Foundation and most particularly the Asia Center. A rich inter-Asian cultural exchange is building steadily and strongly, aided further by important platforms such as the Tokyo International Arts Festival and the TPAM conference in Yokohama, a renowned arts city.

“Communism and capitalism in Asia” was the implied theme for TPAM in 2019, because, as festival director Hiromi Maruoka puts it, “Asian artists are still dealing with this history.” Politics figured heavily in immersive/interactive pieces (100 Cassettes from Japan/Philippines, and Post Capitalistic Auction from China/Japan/Norway), in tech-rich productions (Mysterious Lai Teck, from Singapore), and in lecture performances (Nominal History from Malaysia, Constellation of Violence from Indonesia, and A Haphazard Stanger’s Rough Report from Japan/Peru). More Japanese artists now favor Asian tours and collaborations over similar opportunities in the West, including directors Toshiki Okada and Mikuni Yanaihara, as well as commercial organizations like HoriPro, Gorgeous Entertainment, and Takarazuka Revue (who have many Taiwanese superfans).

That said, for many Japanese theatremakers the impulse to make work palatable to Western tastes remains strong. In the commercial and private sector, this is driven by the desire to generate more international business, a pressing issue in the face of Japan’s current low birth rate and hence declining theatregoing population. At the current rate, as Gekidan Shiki’s Yoshida put it, the audience will be about one-third smaller than it is now by 2050. That’s why Shiki is interested not only in licensing successful works from the West but in creating more universal originals to be toured and licensed as well.

This isn’t driven simply by market forces, though; true to his generation and the kaisha culture, Yoshida says, “We owe it to ourselves and our ancestors before us to make it happen.” He continues optimistically: “It may not take place in my generation, but Gekidan Shiki will be on Broadway. We don’t want to be perceived as the ‘exotic Oriental spice’ but as the basis of the meal, like bread or rice.”

Broadway dreams always beckon, and outside of Miyamoto’s achievement, Japan has yet to make a major mark in U.S. theatre. With all of the exceptional talent, extraordinary productions, and sincere intentions, it is less an “if” than a “when” or “who” will be the first to break onto Broadway (and beyond) with an original expression of Japanese contemporary theatre.

Yuzo Kajiyama, an assistant manager at HoriPro, thinks that the musicals Death Note and Ikiru could be strong contenders for the international market, based on global appeal and title recognition, not to mention their excellent productions. Shochiku too is interested in expanding overseas, as with Kabuki Lion Shi-Shi-O, presented by Panasonic at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas. The 2.5D musical “Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon” The Super Live sold out four showings in Washington, D.C., and New York City late March. And after witnessing the entertaining work of Gekidan Shinkansen or KEREN, I’d be surprised if their flying swords and biting wit didn’t find their way to the States at some point. Takarazuka Revue may seem the most natural fit for the bright lights of Broadway, though its production values and cast size alone could be too much to sustain in the U.S.

But the States aren’t the only foreign place Japanese theatre has found a welcome. Okada’s plays with chelfitsch, for one, have made a splash in Germany and Brussels; the work was even better received there than in his native Japan. And France’s love affair with Japan resulted in Japonismes 2018, a jointly organized cultural season extending from July 2018 to February 2019, designed “to showcase the unrevealed beauty of Japanese art in Paris and France.” Featured were the work of 2.5 Dimensional Musical, Shochiku, Haruki Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore, directed by Ninagawa (produced by HoriPro), kyogen masters the Nomura family (father, son, and daughter), and Okada. Even the humanoid singer, Hatsune Miku, made an appearance. Directors Amon Miyamoto and Satoshi Miyagi both had productions in Japonismes 2018 (YÛGEN, an integration of noh with 3-D technology, and Mahabharata, respectively), and have found regular success in France outside this instance, as both are directors who understand the interests and nuances of other cultures.

“The French adore something that leaves them thinking and questioning, so you can’t be too obvious,” Miyamoto explains. Miyagi, who feels that the French are “more open to shows in other languages than their own,” had the distinct honor of being the first Asian director to open the prestigious Avignon Festival with his Antigone.

In summary: The Japanese are making some of the most exhilarating, entertaining, and innovative theatre anywhere, and it has been evolving rapidly, especially in the past few decades. Even as Japanese theatremakers have begun to craft their work with an eye to accessibility for younger generations and international audiences, they’ve never lost sight of their rich history, traditions, and distinctive culture. Like the omniscient gods and demons in their most ancient expressions, Japanese theatre is looking everywhere and missing nothing.

Cindy Sibilsky is an international entertainment producer and writer/reviewer with a focus on meaningful global cultural exchange. She is curator/guest editor for this issue on Japanese theatre, which was made possible in part by a grant from the Japan Foundation.