One night in February at the Kyoto Theater in the heart of Kyoto, Japan—a city both ancient and modern, where skyscrapers and centuries-old castles coexist—a sophisticated, well-dressed, and 99 percent female audience eagerly yet patiently waited for the show to begin. For many of them, this was not their first or even second visit, as indicated by the merchandise they wore proudly, like badges of honor, in support of their favorite performers.

Superfan-hood comes naturally to the show, titled Touken Ranbu: The Musical—Mihotose no Komoriuta. A semi-historical sword-fighting epic, it’s derived from a Japanese PC/smartphone-app video game, Touken Ranbu Online, in which legendary swords come to life as warriors called Touken Danshi (Sword Boys) to defeat enemies who plot to change the course of history.

The show is sharply divided into two parts: A nearly two-hour Act One unfolds an epic tale of courage and camaraderie, filled with fantasy, drama, flashy musical numbers and intense action scenes with breathtaking sword-fighting—all staged in a style as sharp and angular as a cartoon. The climactic end of this portion left the majority of attendees in tears.

After intermission, Touken Ranbu turns into a full-out concert, with most attendees waving a spectrum of glow sticks in perfectly illuminated choreography, color-coded to reflect the dominant hue of the leading characters’ costumes.

But as off-the-charts as the devotion of these Japanese otaku (superfans) seemed to be, they nevertheless appeared restrained, clapping politely, and generally demurring from showing adoration with screams of praise for their favorite performers, characters, or moments. Their hearts may have been bursting on the inside, but they remained contained and controlled despite their glee.

American audiences had no such reservations when they first encountered this relatively new and rapidly growing Japanese theatrical phenomenon in March, as “Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon” The Super Live became the first “2.5D musical” (as they’re called) to grace the U.S., with performances in both Washington, D.C., and New York City. All shows were sold out well in advance and attendees flew in from 41 states to be the first to see live what was previously only available overseas. In contrast to their Japanese counterparts, American fans shouted and squealed with delight from start to finish; it almost became an interactive experience when iconic moments were recreated onstage. In a scene where the title character first meets her crush, Tuxedo Mask, and has an outrageous musical fantasy about him, the audience was whipped into an absolute frenzy. The enthusiasm is hardly surprising, given that “Sailor Moon” is among the most beloved and recognized anime series in the U.S. since the ’90s, and Sailor Moon manga—comic books—have sold more than 36 million copies worldwide.

Director and choreographer TAKAHIRO blends high-tech production values with timeless theatre tricks, impressive fight choreography, and an electronic pop and rock score by Hyadain with diverse elements ranging from piano ballads to metal music to gothic, tango, and Asian influences. Unlike the two-part Touken Ranbu, “Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon” is a 80-minute thrill ride of non-stop, unabashed entertainment.

Another difference between the two productions: While Touken Ranbu features an all-male cast, similar to kabuki, Sailor Moon boasts an all-female company portraying both genders, a la Japan’s revered Takarazuka Revue Company. The latter is not a coincidence, as Sailor Moon book writer Akiko Kodama has also written and directed for Takarazuka. This approach, a proven formula for success, has its female performers embody the iconic male characters with such elegance and grace that they bring the mysterious men of manga to new and vivid life.

The worldwide popularity of manga (Japanese comic books or graphic novels), anime (Japanese animation), and video games is undeniable. The manga style began in the late 19th century, though its roots can be traced much further back into earlier Japanese art. Since the 1950s it has been a substantial part of the Japanese publishing industry, and saw a major burst of interest and demand beginning in the ’70s, when many popular mangas were animated—a trend that continues to grow rapidly today.

Anime began in the early 20th century but gained wide recognition and acceptance in Japan in the ’60s with series like “Astro Boy,” among others. Its cult following in the West grew in the ’80s thanks to VHS distribution, then DVDs in the ’90s and 2000s. This is when many Westerners met such household names such as Sailor Moon, Dragon Ball Z, and Pokémon. Anime is now a multi-billion-dollar business globally, due to easily accessible streaming services (Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Crunchyroll) offering dubbed or subtitled versions.

According to the annual Association of Japanese Animations (AJA) Report for 2018, published last December, the market size reached 2.153 trillion Japanese Yen ($19.38 billion USD). The total market value for the anime industry has increased continually at the rate of about 10 percent per year since 2013. The latest figures for the manga market cited by the All Japan Magazine and Book Publishers and Editors Association (AJPEA), are 196.5 billion Japanese Yen ($1.77 billion USD) for digital consumption, in addition to a similar number for print.

Meanwhile in Japan, various manifestations of anime, manga, and video games are so interwoven into the cultural fabric that they’ve become commonplace, blending seamlessly into daily Japanese society so that they’re almost invisible precisely because of their hyper-visibility. Hello Kitty recently appeared in an ad for hair removal and has her own festival. Anpanman, a beloved superhero whose head—a red-bean paste-filled pastry called an anpan—graces virtually every children’s product imaginable, as well as snacks and a museum, has more than 80 million books sold as of this past February.

The action hero manga-to-anime franchise Dragon Ball started rolling in 1984 and has never slowed its momentum. Considered the most successful anime brand, it boasts mind-blowing numbers in all forms of media, as well as video game outlets, licensed merchandise, an official holiday in Japan (May 9th, “Goku Day”), and even a religion, Gokuism.

In Japan anime can be seen on TV almost any time of day on a variety of networks, or in cinemas nationwide. Some eventually get a live-action rendition. Manga is consumed by people of all ages, from children to salarymen—both can be seen engrossed in their reading on public transit. It can be picked up on a weekly basis in black-and-white print at the local 7-Eleven (a Japanese-owned franchise, by the way). Genres cover everything from sports and mecha (mechanical, e.g. giant robots) to shōjo (girl-centric) and shōnen (boy-centric) graphic novels, with subgenres such as yaoi/yuri, focused on LGBTQ male relationships or female relationships, respectively. The modes of expression are boundless—there are as many genres of anime as there are for film, and as many categories for manga as for literature.

With such demand it was only a matter of time before an interactive element was introduced to this page-and-screen phenomenon. Otaku seeking community spirit, engagement, even reenactment (through cosplay) have made conventions a booming business. Many draw tens of thousands, and the biggest—Anime Expo in Los Angeles—commands crowds of more than 100,000 attendees for its annual event.

Now stage adaptations made in Japan are finding their way to both Eastern neighbors (South Korea, China and Taiwan) and the West (France and the U.S.). In 2016, the Japan Foundation reported 133 titles of this uniquely Japanese contemporary art form were produced, resulting in 1,889 performances, attended by more than 1.5 million people. According to AJA, the category of “live entertainment” saw a 30 percent increase in sales for the industry as a whole in 2017.

Though stage versions of manga and anime didn’t gain major attention until the early 2000s, they have taken off extraordinarily over the past decade, especially the last five years. The interpretations are staged by companies young and old, and vary from avant-garde to unabashedly commercial. But anime and manga theatre didn’t occur overnight; it took patience, sincere belief, and enthusiasm, plus a dose of trust in a once untapped market for theatre.

The first notable anime/manga live adaptation, after Takarazuka Revue’s The Rose of Versailles (1974), was Saint Seiya (1991). But the current movement can be marked by the 2003 debut of Musical: Prince of Tennis. Makoto Matsuda, the pioneering chairman of Japan 2.5-Dimensional Musical Association, first brought the show affectionately called Tennimu to his stage as an experiment. Even the moniker “2.5D” was coined by fans of the budding spectacles, which combine two-dimensional anime, manga, or video games with live, three-dimensional entertainment. Matsuda said he believes the lack of previous anime or manga-inspired productions may be due to the Japanese performing arts being “somewhat conservative. When we first started manga onstage, people definitely saw it as kind of strange.”

But the gamble paid off, with Tennimu now in its 16th year, having reached some 2.7 million people since its inception and still playing to sold-out audiences. This success led Matsuda and others to consider the interests of less traditional theatregoing audiences who were flocking to the show in droves, primarily young women in their 20s-30s. It’s a phenomenon akin to the burst of tweens, teens, and 20-somethings flocking fanatically to Wicked—a trend that initially caught Broadway off guard but has since led to an increased awareness of the potential for reaching younger audiences.

In Japan that faction typically dominates the “idol groups” scene. Idol stars are often flawless-looking boy or girl groups who sing, dance, and command a godlike status among their adoring otaku. While this kind of fan culture already existed for the 105-year-old, all-female Takarazuka Revue (especially for the actresses portraying the otokoyaku, or idealized male roles), and essentially originated with the adulation of kabuki theatre actors, such repeat-viewing devotion was relatively unheard of among Japan’s theatre community and the fickle, unpredictable miha (trend follower) culture. But the extraordinary response of this audience led Matsuda to develop more 2.5D musicals from popular mangas/animes/video games, including Touken Ranbu and “Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon.”

Another significant contribution made by Matsuda and 2.5D Musicals Association is nurturing and cultivating young newcomers to the stage who rise to stardom in their specialized field. This follows the kaisha model that Gekidan Shiki, Takarazuka Revue, and others employ—a process by which performers are rigorously trained in a company’s style, standards, and legacy. Company members, in turn, are treated like family and enjoy steady, secure, long-term employment, with many going on to becoming even greater stars after their tenure.

This kind of mutual investment and stability is almost unheard of in the U.S. “To date there are about 300 Tennimu alumni,” Matsuda beamed proudly, adding that it was the same for Sailor Moon. Next up: a staging of another favorite, My Hero Academia: The Ultra Stage.

Perhaps inspired by the runaway success of 2.5D, other renowned companies and artists have begun to create their own distinctive versions of theatrical anime, manga, and game adaptations. Some of the more notable and varied stage transformations include Death Note the Musical (2015), which has been performed in South Korea and Taiwan as well as Japan. Produced by HoriPro, it features music by American composer Frank Wildhorn (who has also worked with the Takarazuka Revue). NARUTO (2018) and Super Kabuki II: One Piece (2015) are two other massively popular manga/anime series that were transformed into authentic kabuki versions by Shochiku Co., Ltd. The Takarazuka Revue Company has continued to innovate with lavish adaptations of classic mangas, such as The Widow of Orpheus, as well as ultra-modern pieces, with two shows based on the video game Phoenix of Wright. All productions have been highly acclaimed, vastly expanding multi-generational attendance and further establishing the genre as more than a passing trend.

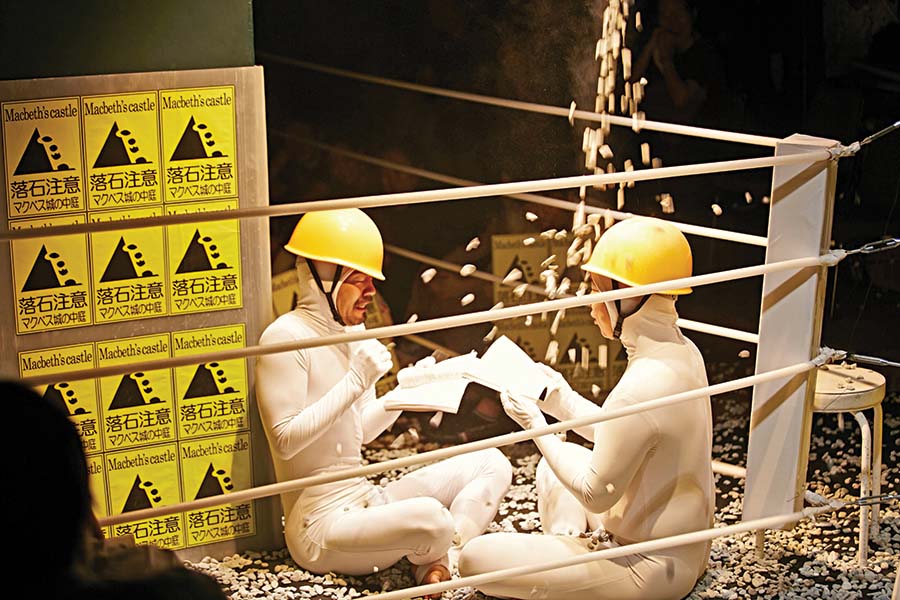

For other more experimental interpretations, the approach may differ but the motivation just as strong. In May, Yu Murai, writer and director for the Theater Company Kaimaku Pennant Race (KPR), brings his hybrid of Shakespeare and manga to New York’s Japan Society. Ashita no Ma-Joe: Rocky Macbeth cleverly juxtaposes the ’60s-era manga Ashita no Joe (Joe of Tomorrow), a story of the transformation of a delinquent young man into a boxing star, with Macbeth. Having seen firsthand the powerful unity and inventiveness of KPR’s company, I have no doubt that this seemingly mismatched mashup will be masterful, profound, and deeply engaging.

In some cases the inspiration has flowed the other way, from stage to screen. Stop-motion animation master Tomoyasu Murata has combined his love for the centuries-old form of Japanese puppet theatre bunraku with his admiration for Czech animation to create the delicate, subtle movements and slowed-down sense of time for his hand-crafted puppets on film. A recent commission from a popular sports manga (top secret until next fall) poses new challenges and opportunities for Murata, while further opening up new artistic avenues for anime and manga.

Straddling both worlds is Kazuki Nakashima, who has since 1985 been a resident playwright for Osaka-based Gekidan Shinkansen (meaning “a new sense of feeling,” and a homonym for a famous Japanese bullet train), and is also a prolific anime screenwriter: Re: Cutie Honey, Guerren Lagann, Oh! Edo Rocket, Kill la Kill, Batman Ninja.

“There is not much of a difference as a writer,” Nakashima noted. “They’re all stories, essentially. But in live theatre there are many limitations to consider, where in anime there are none.”

But despite his proficiency in both mediums, he prefers they not intertwine—which is why he hasn’t been keen to see stage adaptations of his anime work. “I like to keep those separate and write them individually,” he said. Still, both his stage and animated productions are strikingly similar: incredibly complex and astoundingly entertaining. Many of his theatrical works feature fictional characters alongside historical figures: In Dokurojo no Shichinin (Seven Souls in the Skull Castle), the powerful daimyō (feudal lord) Oda Nobunaga from the 16th century, and Minamoto no Yoshitsune, the great 12th century samurai, are put into supernatural situations, with plenty of chanbara (swordplay) action scenes and a disarming sense of humor. “For more than 40 years I have been addressing the issue of how to make something so grand within stage limitations,” said Nakashima.

What lies ahead for this ever-expanding world of theatre? Matsuda offered some predictions.

“Manga, anime, and certain video games are uniquely Japanese cultural creations,” he said. “We want people around the world to see them as such, and we’d like to use creative minds from Japan as much as possible. But what if we can also do something with great talents abroad, like Cirque du Soleil? Perhaps we could create something completely innovative by both preserving Japanese soul and mentality and working with others.”

With newfound openness and domestic demand, the future of such stage expressions could come to resemble the anime, manga, and video games industries themselves: dependent on the vitality of further cooperation, collaboration, and fusion of international talents working together on productions of Japanese origin with universal appeal and eager audiences. These new developments may give us all something to scream about—or, if you’d rather, clap for vigorously but politely.

Cindy Sibilsky covers Japanese culture (including anime) as a writer, moderator, panelist, and producer. She is curator/guest editor for this issue on Japanese theatre, which was made possible in part by a grant from the Japan Foundation.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story misspelled Hyadain as HAYADIN.