Jigsaw puzzles—that’s how Laurie Metcalf occupies her offstage time, she told me recently after a rehearsal for the Broadway premiere of Hillary and Clinton, in which she’ll play a version of the former First Lady and presidential candidate. It’s a tempting metaphor for the way she pieces together her performances from discrete clues and suggestions and choices, or for the way she’s assembled a uniquely distinguished career of stage and screen roles over four decades.

It also feels wrong, on more than one level. Though a typical Metcalf performance comprises thousands of tiny details and decisions—an odd inflection that brings out both a line’s meaning and its opposite, a birdlike twist of the neck at unexpected news, a gait that somehow conveys the pace of her thoughts—there is nothing piecemeal about the effect. She may work like a pointillist, laying down her dots with meticulous care, but the canvases she produces give us portraits of whole people, even when those people are shattered. Indeed if I had to come up with one word to describe her work, it would be soulful (yes, even in the comedies; especially in the comedies).

It’s also a mistake to see her far-flung stage résumé—roles in London, New York, L.A., Chicago (see timeline below)—as scattered or disparate. One of the founding members of the Steppenwolf Theatre Company, Metcalf found in that basement-ensemble-turned-regional-powerhouse both a home base and that most precious of theatrical commodities, a true company ethic. She’d play a meaty lead in one show, do a scene-stealing walk-on in another, contribute sound design to a third. And though she’s no longer based in the Windy City and has appeared at Steppenwolf only twice in the last decade, the ensemble ethos is in her bones, and theatres are her homing beacon in whatever city she’s in; she can’t stay away for long from the collaborative frisson of a rehearsal room, whether it’s at the National Theatre in London or in a North Hollywood storefront. “I’m such a theatre addict,” she told me, without qualification or apology. Said her ex-husband, Steppenwolf co-founder Jeff Perry, “Laurie would perform with a hat on the sidewalk for spare dimes, all the way to large checks with several zeroes—I don’t know if it matters to her at all.”

But there’s a more mundane reason jigsaw puzzles can’t describe what she’s up to: She currently has no backstage time to do them, as she’s in every scene of Hillary and Clinton. The same was true of her two latest Broadway roles, in last year’s revival of Albee’s Three Tall Women and in the previous year’s premiere of A Doll’s House, Part 2. In short, theatregoers are, lucky for us, getting a lot of Laurie Metcalf these days. She’s getting a lot in the bargain too—not just Tony Awards for the last two years running (with little question she’ll be a top contender this year too), but the satisfaction of doing her life’s work at the very top of her game.

“It gives me energy,” she said after an early rehearsal for Hillary and Clinton (now in previews, opening April 18 and running through July 21), her sympathetic brown eyes alight and her taut frame coiled in a plastic chair. She could have been talking about the rehearsal process, in which she throws as many ideas against the wall as she can before sculpting their shards into a final, repeatable performance; or about the adrenaline of performing in front of an audience, which can render her, by her own admission, “too wired onstage, a little too tense. Sometimes I catch myself not breathing.” But in fact she was commenting in passing on an idea that once flickered through her mind: to do Voice Lessons, a zany one-act farce by L.A. scribe Justin Tanner she’s performed in tiny theatres a number of times since 2009, as a midnight show after Long Day’s Journey Into Night, which she assayed in London to resounding acclaim in 2012. No intrepid producer ever took her up on this ploy, but the notion itself captures a few essential Metcalfian details: the whiplash-inducing range of her tastes and abilities, for one, but also her seemingly superhuman stamina.

How would you even do that? I wondered incredulously. Her simple reply summed up the non-zero-sum exchange with both collaborators and audiences that has sustained her spiritually if not always materially since the late ’70s: “It gives me energy.”

Let’s be clear: Though she’s seemingly been discovered anew, thanks in part to her recent Broadway winning streak, her searing, Oscar-nominated turn in the 2017 film Lady Bird, and the TV trauma-com now known as “The Conners,” Laurie Metcalf has, by all accounts, been at the top of her game since she hit the field. Perry remembers seeing her in two productions at Illinois State University when they were both teenagers: Joe Orton’s What the Butler Saw and Lanford Wilson’s Home Free. In retrospect, he said, that double header was “a microcosm of what I would later marvel at: a range of remarkable comedic craft and stunning, authentic, unsentimentalized emotional embodiment.” Behind the scenes in the succeeding decades he bore witness to her “combination of natural ability and fierce, gym-rat persistence.”

Instincts and work ethic: These would seem to be the twin power sources of the Tesla coil that is Laurie Metcalf, from her early days balancing secretarial day jobs with wild nights in Steppenwolf’s Highland Park church basement. Indeed it’s hard to avoid talking about Metcalf in terms of dualities: not just comedy vs. drama (“She always had an uncanny ability for finding the funny in the sad, or the sad in the funny,” as fellow Steppenwolfer Randall Arney put it) or small vs. large (“I was warned when I was gonna step into sitcom land that you’re acting in front of a camera now, it’s not a 200-seat house or a 1,000-seat house, and so you’ve really gotta pull back,” Metcalf told me, “but I found that not to be true, really, if it’s based in reality”). One of her most striking and oft-noted polarities can only be thought of as a kind of double consciousness.

“She can be in absolute emotional chaos, as far as we can tell, but while working with her you realize she’s also capable of the weird double awareness that the person in the third row of the balcony coughed too much or got up to leave,” marveled Perry. Joe Mantello, who directed her in Three Tall Women and is doing the same in Hillary and Clinton, recalled a moment when, while rehearsing Sharr White’s play The Other Place, Metcalf was “in the middle of a devastating scene, and did this bit of business that was so funny, she looked out at me and busted a gut—then went right back into it.”

Tales of this uncanny ability being deployed in the commission of merciless onstage pranks are legion. Said Anna D. Shapiro, Steppenwolf’s current artistic director, who first directed Metcalf in Bruce Norris’s Purple Heart in 2002: “She’s well known for being able to be in the throes of anguish in a role, then flash someone offstage.” For her longtime Steppenwolf compatriot Rondi Reed, Metcalf’s practical jokes were an education in themselves. “People have said to me, ‘You don’t ever seem to crack onstage,’ and I say, ‘That’s because I had to deal with Laurie Metcalf all my life. If you’ve been subjected to that, you have no worries.’”

But this isn’t just the idle foolery of a pro showing off; it speaks to a larger capacity. Lucas Hnath, who wrote A Doll’s House, Part 2 and Hillary and Clinton, thinks that Metcalf’s astounding ability to “occupy two contradictory mental-scapes at the same time” makes her an ideal interpreter of his work. “Her brain is like a supercomputer—like having extra processing power in the room,” said Hnath. “She’s a highly technical actor without sacrificing emotional integrity, which is the perfect actor for me. I like to work technically, but there’s that risk of it being cold and steely, and you don’t have that with Laurie.”

For her part, Metcalf thinks of these as complementary muscle groups. “I hope that after all these years that both sides are equally strong, both the technique and the instinct,” she said. “So if they’re both working together, that’s what allows me to do that—to have one foot still in the emotional, but technically be able to remove myself.”

The careful assembly work begins as soon as she gets a script and looks for “a kernel in there where it lands with me emotionally, and I think, ‘I know exactly how to do this.’” She then starts “daydreaming how I might play it; I visualize it in a blurry way,” including rough stage pictures which—interestingly, for an actor who is avowedly camera-phobic—include herself. “I think I have a third eye that is watching,” Metcalf said, though she was quick to add, “It’s certainly not a director’s eye.”

Directorial or not, this extrasensory perception is more than just a freak talent. Mantello said that Metcalf, who is “always aware of the big picture,” puts that awareness in the service of storytelling; if she has a third eye, it’s looking on from the theatre seats. “It feels like, being in the room with her, that her goal is to make the kinds of choices that will give the audience the ride of their lives,” said Mantello. “She’s willing to do anything to make that happen.”

Anything indeed: Colleagues gleefully related instances of her pronounced lack of vanity, bordering on self-abasement. Mantello laughed about the hideous wig she insisted on wearing in David Mamet’s 2008 Broadway comedy November. Shapiro said that Metcalf taught her “how critical humiliation is to humor.” Hnath mentioned her eagerness to vomit onstage, including in one scene in A Doll’s House, Part 2 in which that impulse, though unrealized, helped underline a problem area of the play that called for a dramatic solution. “She was dramaturging,” said Hnath admiringly. In a 2006 production of All My Sons at Geffen Playhouse in L.A., she won permission to puke from director Randall Arney. For the climactic moment when Kate Keller reads her son’s suicide note, Arney said, “Laurie came to me with a twinkle in her eye and said, ‘Do you mind if I throw up a little in the hedge?’ She’s so good at finding an odd, funny way to expose a deep, deep hurt.”

“I try early on to look for unpredictable ways of attacking a line or a physicality that seem to work against maybe what your initial thought of the moment might be,” said Metcalf, who at one point in our interview got up to demonstrate a crotch grab she added to undercut one of Mary Tyrone’s tenderer monologues in Long Day’s Journey. “I just try to think outside the box from the very beginning.”

You might think that a taste for the extreme choice—“Go big or go home, that might sum up my approach,” she said—would make Metcalf a scenery chewer. No question she can command the stage, from her legendary 19-minute monologue as Darlene in Steppenwolf’s Balm in Gilead to Nora’s perorations in A Doll’s House, Part 2 to the devastating theatre-scene-on-TV she did with Louis C.K. on “Horace and Pete.” And anyone who saw it still talks about a moment in a 2010 New Group production of A Lie of the Mind in which her character crawled across the stage with a pair of socks in her mouth, like a dog delivering a newspaper.

But in part due to her long years of working in an ensemble, there’s nothing self-aggrandizing about even her wildest gestures. “Size without bravura” is how her Steppenwolf colleague Austin Pendleton characterized it. “It’s size without an announcement of size.” Arney described it in terms of her against-the-grain acting strategy, the way she marshals emotional resources so that she’s “so full of whatever that character is, up to her ears, that it’s a process of pulling back to keep the lid from coming off. We end up watching these powerful moments in spite of the character. She’s pulling against an emotion the character doesn’t want to reveal—which makes sense, because we usually don’t want to reveal ourselves.”

In short there’s a method to the madness. All those counterintuitive instincts—what L.A. playwright Justin Tanner calls Metcalf’s “perverse imagination as an actor”—are not mere quirks for quirk’s sake, but key signposts on her itinerary. “Sometimes it’s working backwards,” she explained. “If I know I’m in this emotional state for one part of the play, I think backwards to, where’s the furthest I can start away from it so I have the longest to travel?”

Maybe that’s why her characters’ journeys are so legible. Said Hnath, “She’s not content to be a passive recipient. There’s some part of her that restlessly tries to find the action that will help us see something.” Mantello echoed that, saying, “She makes thought athletic. When you’re watching her just sitting there, she’s never in repose, because she’s activating thinking. You watch her think.”

“I’d rather be busy than not. I’m happiest when I’m busy,” says the character Hillary in Hnath’s new play, set at a pivotal moment during the 2008 Democratic primary when her rival, Barack, has scored an upset in the Iowa caucus. Hnath insists that the play is set in an “alternate universe,” and that its Bill (played by John Lithgow) and Barack (Peter Francis James) are no more supposed to be the “real” articles than is Metcalf’s Hillary.

“If I was asked to do an impression, I wouldn’t be cast in the play, because I can’t do it,” said Metcalf, not entirely convincingly. “I want to be as different as I can be, physically and vocally.” So she’s avoided studying videos of the real Hillary, she said. Of course, no sentient adult who lived through the last few decades needs to do research to access either of the Clintons’ faces and voices, and the play is banking on—and playing with—a similar availability in audiences.

“Sometimes it’ll be like, ‘Okay, I know who they’re supposed to be, and I’ve always wondered what they were like in a room together’—but it’s not them,” said Metcalf. “It’s a weird optical illusion where the focus is gonna go in and out.”

Surely Laura Elizabeth Metcalf of Carbondale, Ill., feels some affinity for Hillary Diane Rodham of suburban Chicago? If not in her origins then in her destiny, as a fellow woman in a male-dominated field, frequently underrated, taken for granted, forced to perform in the shadow of men? Metcalf seems equivocal when asked, and not simply because Hnath’s Hillary isn’t supposed to be the “real” one. But Hnath could have written the line about being happiest when she’s busy to describe Metcalf, who admitted she doesn’t savor downtime between gigs, and whose supposed leisure activities are more intense than most paying jobs: Where some may take up knitting, for instance, Metcalf went so far as to shear and card her own wool from pygmy goats she personally birthed and raised on a farm in Idaho. (Her model-farm-wife phase ended when Metcalf said she realized, “This is fucked—this is way too much effort.”)

While not conceding much about her own links to the real-life Hillary, Metcalf did admit that, like many, she felt “completely” torn apart by the 2016 election. And though the play’s setting in 2008 means it isn’t poised to relitigate either the contentious Bernie-vs.-Hillary primary or the intensely polarized general-election campaign against Trump, it has no shortage of moments of reckoning between Bill and Hillary, between Hillary and Barack, and between Hillary and her unseen public and posterity. This Hillary, presumably like the real one, chafes at her thankless position in an impossible limbo somewhere between the spotlight and the shadow of her problematic husband, where she’s asked to somehow mean all things to all people yet feels as constrained by sexist expectations as by her own shortcomings, if these can even be disentangled.

Yes, it’s an “alternate universe,” but also, yes, Metcalf said she relishes the chance to “give the audience a way to feel a kind of catharsis in being able to hear Hillary say some of the stuff she says in this play. I’m sensing that that’s what the audience might need. I think it’s gonna be helpful for them. Emotionally.”

Which raises the question: What does Metcalf need, emotionally? What drives her? How does one of our greatest stage actors do it? The source of an actor’s work is inevitably themselves and their own life experiences, but there’s a delicate, not to mention properly private, alchemy between the role and the person, which Metcalf and her colleagues—and I—do well to respect. Peek too far behind the curtain and the magic may be spoiled. The rough personal sketch: Metcalf has been married and divorced twice, has lived in a number of places, though mostly in L.A. (despite not caring much for it), and has raised four kids, among them Zoe Perry, also an actor, who currently stars on “Young Sheldon” as a younger version of the tightly wound mom character Metcalf created on “The Big Bang Theory.” Perry, who acted with her mom in the Broadway run of The Other Place, was telling me about her mother’s approach to an individual role, but she could have been describing the odd directionality, amid ups and downs, of Metcalf’s craft and career when she said, “She’s always driving toward something. It’s a labor of love, but it’s a labor; she leaves no stone unturned.”

Steppenwolf’s Shapiro offered an analogy to illustrate the sharp divide between Metcalf on- and offstage. Recalling a college boyfriend who was a swimmer, she said, “He was incredibly elegant in the pool, but when he would get out and walk on the earth, his body was cumbersome; he lumbered along. For Laurie, when she’s able to put on a mask, that’s like being a swimmer; she is more comfortable when she is transformed. That is how Laurie communes with the world. She does it as an actor and as a mom, and that’s it. When you recognize that’s the way a person gets oxygen, you do everything you can as a colleague to get them to the air. I don’t think she could live without it. I think we’re all kind of lucky that she’s like that. I don’t know how lucky she is.”

As the sole founding member from one of America’s great theatre companies who is still crushing it in leading stage roles, luck may have nothing do with it. As Pendleton said, “The astonishing thing is that she’s as great as she always was. She had nowhere to go but down, but she hasn’t. There are different textures in the work now, but the quality is as electric as it was in 1979. It’s hard to be that good for that long.”

The key to such mastery may be a kind of letting go. I asked Metcalf about Darlene, the naïve prostitute from Lanford Wilson’s Balm in Gilead, whom the playwright described bluntly in a stage direction as “stupid.” If she’s able to let part of her mind step outside a play, I wondered, is she also willing to step outside a character and pass judgment on her?

“I don’t worry about laying into the negative aspects of a character,” she said by way of explanation, in the process offering a kind of manifesto for her work, from her intellectually disabled Laura in Steppenwolf’s seminal The Glass Menagerie all the way up to her still-gestating Hillary. “I actually find it kind of endearing that a character can be selfish, mean-spirited, ugly. I embrace the ugly, because generally I have provided the character also with a moment of the opposite. With Darlene, it was fun to lay into the stupid, because when she has moments of clarity that she doesn’t even know are coming across, it’s so heartbreaking to an audience. You know? I guess it’s not a judgment. It’s like a trust that the audience will see deeper. It might take a while. But when they do, then you’ve let your character earn their sympathy.”

An earlier draft of this story erroneously wrote that Peter Jay Fernandez was playing Barack in Hillary and Clinton.

A complete timeline of Laurie Metcalf’s stage career

1976

STEPPENWOLF ― The Lover

1977

STEPPENWOLF ― Our Late Night

Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead

Mack, Anything Goes Over the Rainbow

The Sea Horse

1978

STEPPENWOLF ― Home Free

Sandbar Flatland

Fifth of July

1979

STEPPENWOLF ― Exit the King

Waiting for Lefty

The Glass Menagerie

1980

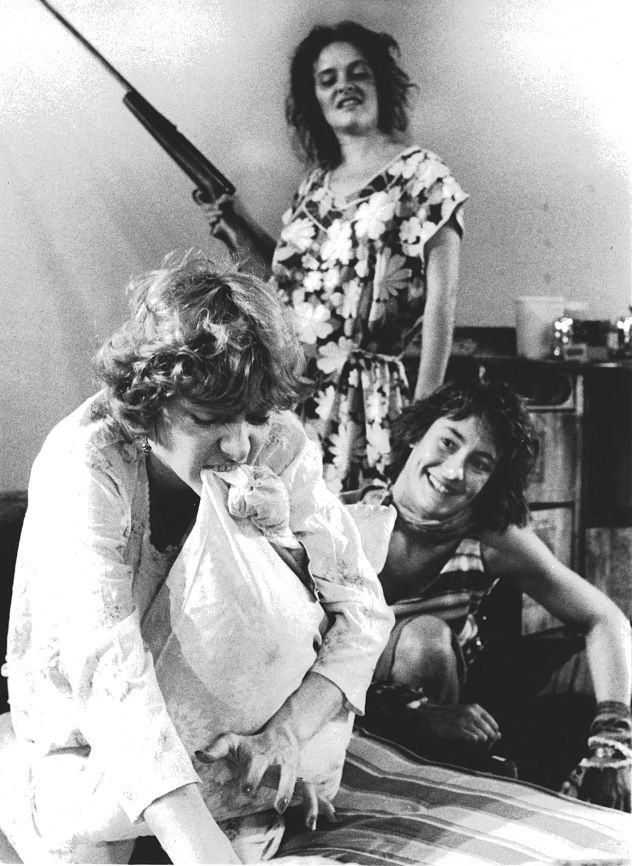

STEPPENWOLF ― Balm in Gilead

Quiet Jeannie Green

Absent Friends

Savages

WISDOM BRIDGE ― Getting Out

1981

STEPPENWOLF ― Arms and the Man

Balm in Gilead

Big Mother (as director)

Action

Waiting for the Parade

1982

STEPPENWOLF ― And a Nightingale Sang

True West

Loose Ends

COLUMBIA COLLEGE ― The Member of the Wedding

1983

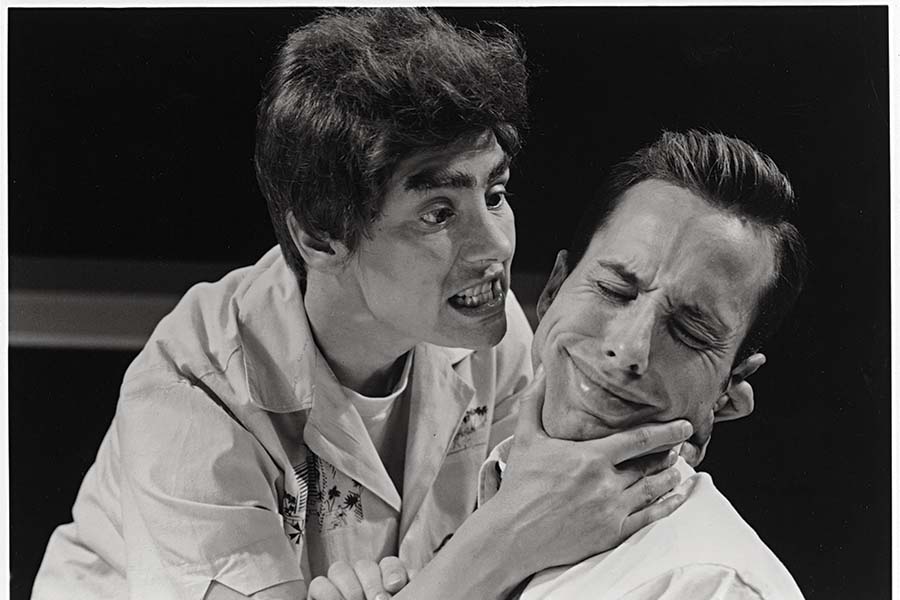

STEPPENWOLF ― Cloud Nine

Miss Firecracker Contest

NORTHLIGHT ― Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

1984

STEPPENWOLF ― Orphans (sound design)

1984

COLUMBIA COLLEGE ― The Man Who Came to Dinner

OFF-BROADWAY ― Balm in Gilead

1985

STEPPENWOLF ― Coyote Ugly

KENNEDY CENTER (D.C.) ― Coyote Ugly

1986

STEPPENWOLF ― You Can’t Take It With You

OFF-BROADWAY ― Bodies, Rest, Motion

WILLIAMSTOWN THEATRE FESTIVAL― School for Scandal

1987

STEPPENWOLF ― Little Egypt

Educating Rita

OFF-BROADWAY ― Educating Rita

1988

STEPPENWOLF ― Killers

1990

STEPPENWOLF ― Wrong Turn at Lungfish

Love Letters

1992

STEPPENWOLF ― My Thing of Love

1994

STEPPENWOLF ― Libra

1995

BROADWAY ― My Thing of Love

1997

CAST THEATRE (L.A.) ― Pot Mom

Happytime Xmas

1998

STEPPENWOLF ― Pot Mom

CAST ― Party Mix

1999

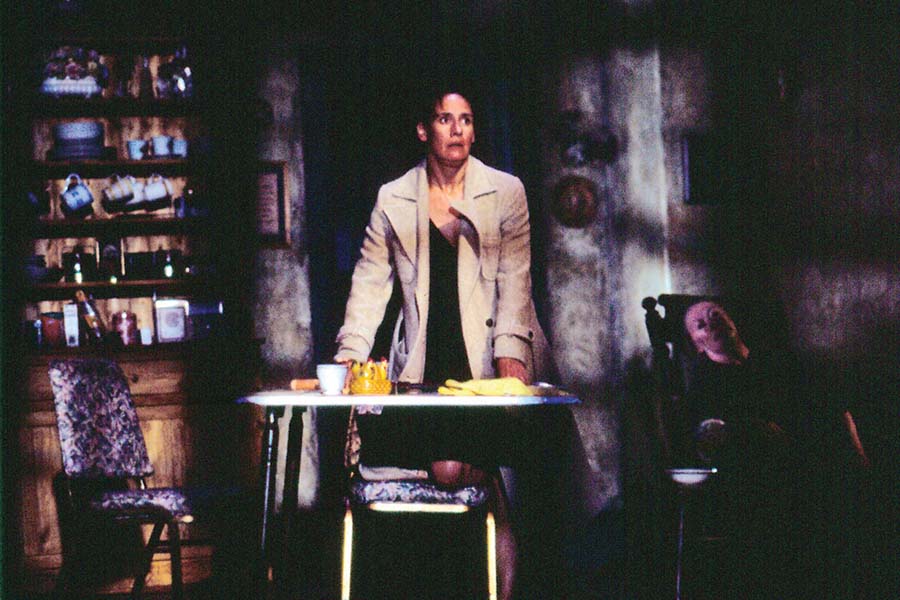

STEPPENWOLF ― The Beauty Queen of Leenane

CAST ― Still Life With Vacuum Salesman

2001

GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE (L.A.) ― Looking for Normal

NATIONAL (LONDON) ― All My Sons

2002

STEPPENWOLF ― Purple Heart

2004

STEPPENWOLF ― Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune

2006

GEFFEN ― All My Sons

THIRD STAGE (L.A.) ― Pot Mom

2007

GEFFEN ― The Quality of Life

2008

BROADWAY ― November

AMERICAN CONSERVATORY THEATER (S.F.) ― The Quality of Life

2009

ZEPHYR (L.A.) ― Voice Lessons

BROADWAY ― Brighton Beach Memoirs

2010

NEW GROUP (N.Y.) ― A Lie of the Mind

STEPPENWOLF ― Detroit

THEATRE ROW (N.Y.) ― Voice Lessons

2011

MCC (N.Y.) ― The Other Place

SACRED FOOLS (L.A.) ― Voice Lessons

WHITEFIRE (L.A.) ― Voice Lessons

2012

WEST END ― Long Day’s Journey Into Night

2013

BROADWAY ― The Other Place

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER ― Domesticated

2015

CIRCLE X (L.A.) ― Trevor

BROADWAY ― Misery

2016

STEPPENWOLF ― Voice Lessons

2017

BROADWAY ― A Doll’s House, Part 2

2018

BROADWAY ― Three Tall Women

2019

BROADWAY ― Hillary and Clinton