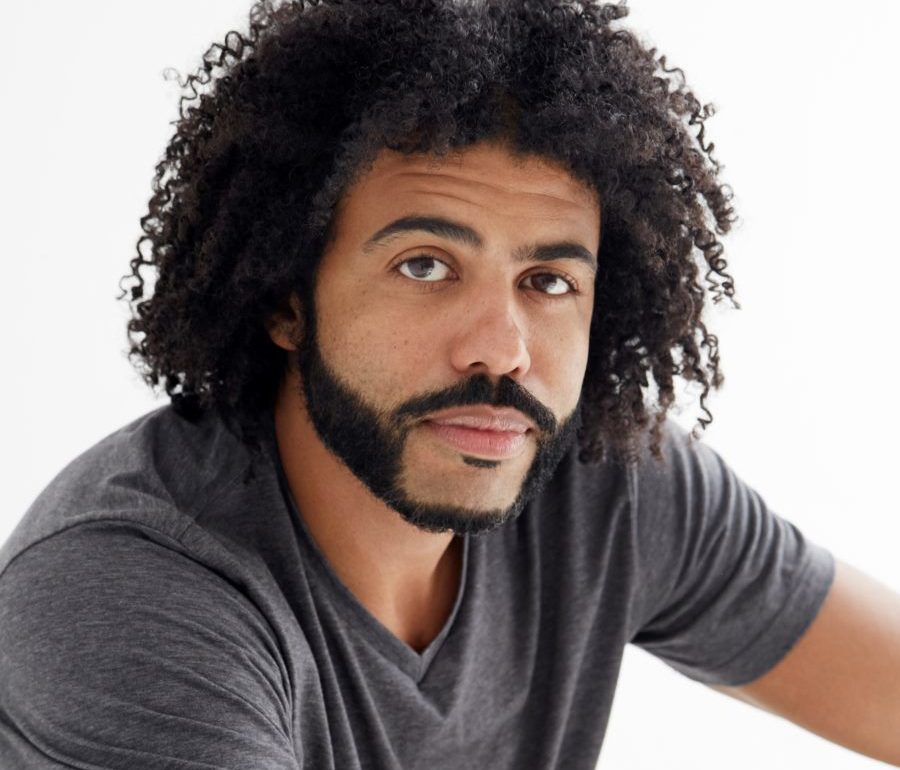

Daveed Diggs hasn’t been doing much theatre lately. After winning a Tony Award for playing Marquis de Lafayette and Thomas Jefferson in Hamilton (you may have heard of it), Diggs pivoted to Hollywood, taking on recurring roles in “black-ish” and “The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt.” Last year he produced, wrote, and starred in the film Blindspotting, about gentrification and race in Oakland, Calif., where he was born. He also starred in “Velvet Buzzsaw” (for Netflix) and will next be seen in “Snowpiercer” (TNT).

But he’s very happy to be back in front of a live audience this month for the world premiere of White Noise by Suzan-Lori Parks, his favorite playwright, at the Public Theater. The play is about a diverse, well-off group of friends whose lives are shaken when one of their own is racially profiled by a police officer. White Noise runs March 5-May 5.

DIEP TRAN: I was reading the summary of the play, because I wasn’t given a script, and it reminded me of Blindspotting.

DAVEED DIGGS: They are pieces in conversation for sure. They definitely are both examining how not just people of color, but all of us, deal with something it turns out is foundational about this country, that we often like to cover up with our politics and language. It’s about some of the inherent power dynamics that exist in interracial friendships, but also in inter-gender friendships. One of the great things about it is that all the characters in the play are really doing well. Everyone has their own hardships that they came from, but everyone is pretty successful by any normal American standard. In examining how race was designed to function in this country, they get in touch with a whole bunch of other shit—with a bunch of rage, with a bunch of fear—and start to doubt all the ways that they’ve been successful.

Did you read that Wesley Morris essay about black and white friendships and how they’re depicted?

I didn’t.

He was comparing stuff like Jeremy O. Harris’s Slave Play and Blindspotting to Green Book and Driving Miss Daisy—race narratives penned by Black people versus those penned by white people, and how there’s often a myth that these friendships are restorative when white people write on the subject, but when you have Black people writing about it, it becomes something a little bit more complicated, where there’s a negotiation of space and power.

I think I would agree with that, although white people were also writing Blindspotting. I think in examining the ways those pieces function differently, you can’t ignore the power dynamics in interracial relationships and how they affect everybody. I think one of the things that this play does particularly well is that it is not just Black people or people of color who are dealing with the legacy of slavery. We all are. The whole country is existing within it. No matter who you are, in some way or another, it makes you somebody that you don’t want to be or that you don’t think you are. We have to sort of acknowledge how we are all complicit in it.

What kind of conversations are we not having that you think we should be having?

There is a master-slave relationship that this country is built on, and it is still designed for that to be a very successful relationship. Most of us who don’t believe that is okay are working really hard every day to not buy into it. But it is the easiest way to be successful, right? For all parties.

I think that’s the conversation I find myself having with this show a lot that I think I’ve never had before. This is a crazy thing to say, but this is the kind of shit I’ve been dealing with in rehearsal: I might feel safer if I was closer to a slave. Does that make sense? If I aligned myself more closely with that role, if I sort of willingly gave up my freedom in a lot of ways? Some of the things that make me unsafe are the things that make me free. Whereas if I did not take those things, like gave those things up willingly, I might be treated with a different level of safety. I might feel less likely to be accosted by the police.

It’s like the illusion of safety is almost more dangerous, because then you don’t know who or where your enemies are.

Yeah, but also, if I were not in any way dangerous to the inherent power structures of the country, I wouldn’t be targeted, you know? There would be no reason to target me. That’s sort of for everybody. If you’re not threatening the patriarchy, then you’re not—you know what I’m saying? I think most of us who consider ourselves woke, we are actively fighting for everybody to not have to fall into those roles. But those roles exist and they were set up to be successful. And one of the things you lose by breaking them is protection.

I’ve read another interview where you talked about having been racially profiled and harassed by police officers. For you to go to work where you’re recreating that dynamic and there’s really no escape there, how do you stay sane and balanced?

The theatre is actually a very safe place to work through these things. It’s the opposite of being profiled, because we’re dedicated to the work and everybody in there is creating a safe space to examine these things. It actually is kind of a balancing force in and of itself, I think.

But I have really good friends who make me laugh a lot and help me not take my work home with me too much. Then I make music, too, so that’s also helpful [Diggs is part of the hip-hop trio clipping.]. Particularly rap music is a good way to feel powerful, you know? People who don’t participate in the culture give the sometimes aggressive nature of it a lot of negative attention. But realistically, they’re fantasies of power for everyone who participates in them—it’s often participated in by people who are relatively powerless. Rap music is a kind of escapism, and part of what you do as a rapper is make yourself into a superhero.

You’re based in Los Angeles now?

Yeah.

Well, welcome back for a bit.

It’s nice to be here. The last few years I have had not a great relationship with New York, but this time feels really good. The Hamilton experience here was so intense, and it became a pretty stressful place for me to be. That was a show that, at the bottom of it, it’s a bunch of friends getting together and making rap songs. I was involved with that show for a long time because my friend wrote it and asked me to come along for the ride. Everything on the inside of it felt very small, and everything on the outside of it felt very big.

It’s nice to hear someone be honest about that aspect of fame. I think a lot of people want fame and they don’t realize what it entails.

Yeah. It’s a lot of answering the same questions.

Have I asked you stuff that you’ve answered many times before?

No, you have been fantastic. And we’re talking about a different show. Also, any time you have time to actually sit and talk with somebody, it’s gotta be great. It’s more the five-second sound bite: how do we spend four minutes together and get a bunch of information about a thing that I spent four years on, you know? That Lin-Manuel Miranda spent nine years on. Sort of boiling that down in to talking points is, like, why do we even do that? You’ve read it and you’ve seen it and you have summaries of it. What’s the point?

You were a middle school teacher and you worked with a lot of young people. There are always these questions that artists wonder about: How do you get young people into theatre—especially poorer, less white people? What do you think would help?

The percentage of poor kids of color who are going to be excited about theatre is the same as any group of kids. It’s just you have to make it available to them. When I was in high school, we were down the street from Berkeley Rep and they would do a really great job about letting us come see previews. The educational outreach director there, Cliff Mayotte, used to just let us come sit in their library and read all their plays, or if there were interesting talkbacks, he would let us come to them. I think that relationship with an actual, practicing theatre is why I love theatre. I was given the access to it. And it was allowed to be on my terms, and the space was opened up for all of us. We used to have poetry slams at that theatre.

I think the Broadway for-profit model has a hard time with this, because you have to sell all of those seats for so much money in order to keep the lights on during the run of the show. So it’s gonna be tricky for you to do the kind of outreach necessary to really bring folks into it.

This isn’t me trying to be an asshole, I’m just really curious, because I think a lot about access and I think a lot about who can afford tickets. So when you were doing Hamilton, a show you made with your friends, it was in part to let kids of color see themselves, but most of them couldn’t get in because the tickets were being bought up by people who had money and had access. How did that make you feel as a performer?

It wasn’t great. But what was great were the hundreds of student matinees that we did, and the sort of commitment to get every 11th grader in public school in New York to come through that show. I’d never heard of any show that did that before. Those performances were different; they were better. And then, not only that, but the educational outreach element—there was curriculum built into it, so kids were getting to create their own sort of Hamilton-style retellings of historic events in their schools.

We were at the Richard Rodgers Theatre all day on those student matinee Wednesdays. We would come, like, at 9 in the morning. These kids would show up, and they would perform the thing that they wrote for their peers. Those were my favorite days.

Do I wish that the regular audiences, the everyday audiences, were a little more diverse, not only in terms of ethnicity but in terms of age? Yes, obviously. But at least there were some attempts to try and figure it out, because you have to do something to combat the fact that all of the tickets are getting bought up and resold for rates that are really for the top of the one percent. People were paying insane amounts—thousands, tens of thousands of dollars for a couple of tickets.

Tens of thousands?

Like Lin’s last show! The StubHub prices for those tickets were things nobody had ever seen before.

It’s a weird irony when you’re like, I can’t even afford my own show.

Yeah [laughs]. There’s no way!

Since you’re a Bay Area native, what’s a thing about Bay Area theatre that not many people know?

It is so vibrant. There’s so much of it. It feels like Chicago in the sense that there are places really committed to developing new work. There’s places like Berkeley Rep or American Conservatory Theater or Marin Theatre—the larger companies there are sort of Broadway-bound, developing work for commercial spaces. There’s also a bunch of really small theatres that are committed to doing really out-there stuff.

What are some of your favorite theatres there?

I love the SF Playhouse. They were a second home to me in a lot of ways when I was coming up. I love a little tiny theatre called Custom Made Theatre. That was my first professional gig with them. I did a Václav Havel play with them just out of college [Temptation]. It was a hard play, the final stage direction was basically that the whole theatre burns down. Very Havel [laughs]. And we were performing in a converted office space in the Mission.

Do you ever think you’ll go back to doing plays in tiny 99-seat houses?

I love performing in smaller houses. I think you get a different kind of connection there. I’m excited to be doing any play, period, after spending a couple years being in front of a camera. This is a very welcome return. You get a different kind of intimacy in a small space, and I think everybody gets to know each other a little better.

As much as I loved performing on Broadway, I don’t care if I ever do that again. I like telling stories in places where everyone is part of the storytelling. I get much more out of it when we all have to be in it together, when the audience isn’t hidden and where you can really see all the energetic exchanges going on and we’re all in conversation together. We’ve spent however many weeks with me working on my ideas on it. Now every night we get a new group of people in there and have to build the thing from scratch again for this group. We all have to decide what this play is tonight. I think that kind of real in-the-moment work is the thing that’s exciting for me.