First, a disclaimer: This is not a story about how Black theatres grapple with issues of inequity, though that certainly is a part of their history and their founding, which I’ll try to contextualize here. This is a story about how art is made against the odds, how new voices enter the field despite covered ears, and how hearts are opened through the power of live theatre.

The American theatre has largely been conceived as a white American art form designed to tell the stories of white Americans to each other, evoking nostalgia and escape every time the curtain rises. This has been the norm for much of this country’s history, but the kettle has been whistling loudly for the last 40 years with the message that it’s long past time for American stages to reflect and present more of the range of American life. Indeed it is no coincidence that the regional theatre movement, which began in the early 1960s, and the Civil Rights movement were celestially aligned. The full realization of human rights includes, though it is not limited to, the sharing and appreciation of culturally specific stories, customs, and art. That is why in 1966, when Stokely Carmichael pronounced in his Black Power speech that “a broad nose, a thick lip, and nappy hair is us, and we are going to call that beautiful whether they like it or not,” it incited an artistic revolution. African American artists took that as a charge to move their narratives from vaudeville and the folklore tradition to the theatre with an “-re.”

The steeping of the Black Arts Movement within the Black Power Movement also presented an opportunity for African American artists to imagine themselves in roles they were often prevented from playing. There could be a Black Ophelia or Julius Caesar, a bronze Willy Loman or Blanche DuBois. In fact, many Black actors went to theatre school and studied the Greek tragedies and Shakespearean classics, but had been relegated to playing servant and clown roles, if they were given parts at all. Most of the country’s African American theatres were founded to give Black actors an opportunity to play diverse roles and to offer Black playwrights the chance to tell honest, original stories about their communities.

As August Wilson said in his famous “The Ground on Which I Stand” speech at the 1996 TCG conference, the Black Power movement of the ’60s was “the kiln in which I was fired, and has much to do with the person I am today and the ideas and attitudes that I carry as part of my consciousness.” The same movement that bore Wilson also birthed most of the nation’s Black theatres, and many of them persist today, training artists of color, providing opportunities for marginalized artists to see their work onstage for the first time, filling in the gaps of arts education for their communities, and, most importantly, entertaining and enlightening audiences with powerful stories.

When Barbara Ann Teer founded National Black Theatre in Harlem in 1968, the neighborhood was reeling from the riots that were wreaking havoc across many Black communities after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Her mission was to create a space to celebrate Black liberation through art. Teer was a classically trained dancer and actress who had toured with mostly white companies, but she knew that the best way to use the breadth of her talent was to create something of her own. That is why she decided to anchor herself at 125th and 5th Avenue, which she called the “most recognizable street in the world.” Her theatre still stands there today. Fifty years later, her daughter Sade Lythcott, the theatre’s CEO, carries the torch of creating space for Black people to get free.

“For so long Black people have been in flight,” says Lythcott. “Ever since we set foot on this continent, we have never been able to make a real sense of home, so we make it mostly through our art. Our vision is to be a home away from home for Black artists who want to lay down the burden of this experience.”

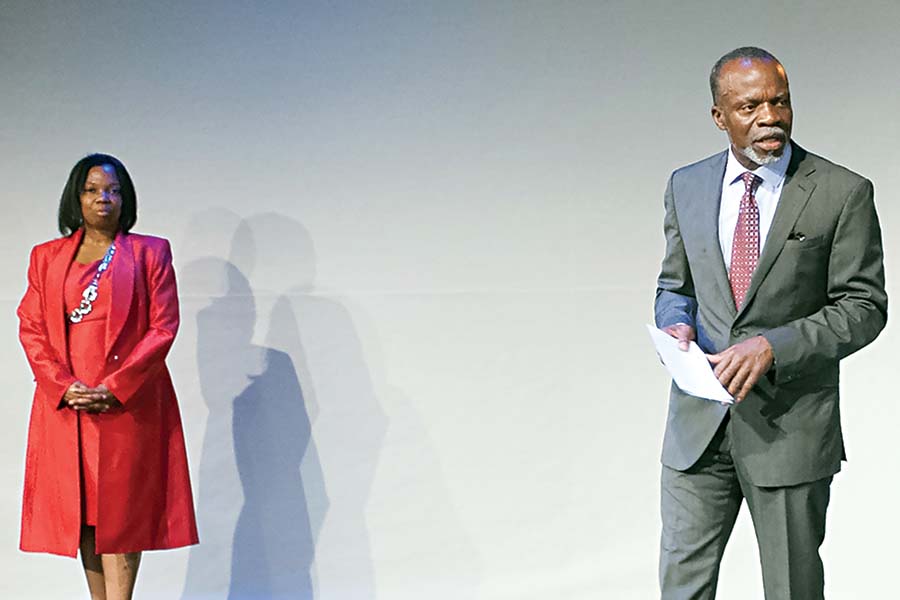

Lythcott continues to build upon her mother’s rich legacy, which included world premieres by Amiri Baraka and Ntozake Shange. Along with artistic director Jonathan McCrory, Lythcott continues to put brave, revolutionary work in the limelight by staging works by performers and playwrights including Rain Pryor and Dominique Morisseau. The theatre houses “I AM SOUL” residencies for African American playwrights, directors, and producers to help them develop new work or refine existing work. They are also crossing oceanic borders, creating National Black Theatre of Sweden and developing a musical in South Africa, all while raising capital to redevelop the Harlem space.

The same need that motivated the founding of theatres in the ’60s and ’70s persists today. According to the Actors’ Equity 2017 Diversity Study, African Americans received just 8.63 percent of all principal contracts in plays, and 2.3 percent of stage management contracts. This may be one reason most African American theatres are not Equity houses, but instead operate under special agreements when the need arises.

This is how African-American Shakespeare Company in San Francisco has operated since 1994, giving local talent the opportunity to tackle starring roles in The Tempest, Much Ado About Nothing, and The Winter’s Tale. Sherri Young started the theatre just two years after graduating from the MFA program at American Conservatory Theater, with the goal of creating a pipeline of classically trained Black actors who could work at any theatre in the world.

“In the ’90s theatre companies across the country were doing colorblind casting, because they were trying to bring diversity, but the work was still very Eurocentric,” Young recalls. “My community was not interested in seeing a show just because there was a Black person or a Latino on the stage. I thought to myself, ‘These big theatres don’t understand how to speak to communities that aren’t their own.’ I thought that [my friends and family] needed to see the work onstage in their own community to get the relevance. That’s how I thought of African-American Shakespeare.”

In recent years, Young and artistic director L. Peter Callender have expanded their education programs, teaching literacy through theatre at local schools and Boys & Girls Clubs, hosting acting workshops, and inviting teachers to preview shows whose texts they are teaching in their classrooms. Alongside work by Shakespeare the theatre has also started producing African American classics: The Colored Museum, Jitney, For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf. Callender is also working on a script of his own about a family living in South Africa immediately after the end of apartheid. The pointed question he’s mulling: “How could 44 million black people forgive 7 million white people without there being a bloodbath?”

He gives something of an oblique answer of his own. “I am burned out with the slave narrative,” he says. “I would like to see more power-based, youth-based, and female-based [work]. I want to chronicle what’s happening with #MeToo, Hands Up Don’t Shoot, and what’s happening at the Southern border. August Wilson wrote 10 history plays, and I want us to pick up where he left off, similar to what Dominique Morisseau is doing.”

The need for diverse, soul-lifting narratives is what Nate Jacobs had in mind in 1999 when he founded Westcoast Black Theatre Troupe in Sarasota, Fla. At the time, the Florida A&M University graduate found that he and his friends were only getting cast in servant roles at Asolo Rep, as they rarely placed Black actors in principal roles in the classic plays that composed much of their programming. Westcoast Black Theatre Troupe thus became an outlet for African American artists to showcase their talents. For the first few years, the theatre was largely run from the trunk of his car, staging performances of Black classics, such as James Baldwin’s The Amen Corner, wherever they could find space. Now they have a brick-and-mortar location, and their most recent musical, Marvin Gaye: Prince of Soul, was produced through special arrangement with the late singer’s family. It has been a runaway hit for the theatre.

Jacobs has focused on creating original musicals and cabaret performances as a way to start important conversations while also making sure that everyone feels included. He believes that a lot of Black theatres get stuck producing shows that throw into white audiences’ faces the way their ancestors treated Black people. He prefers to finesse the way that material is presented.

“A certain type of patron is not going to come to your theatre and pay money to be slapped in the face,” Jacobs reasons. “It’s not that I cater, or play down our history, but I’m very strategic. My stuff has always existed for a diverse audience of all intellects, races, and colors. Everybody can relate.”

When Jacobs thinks about what keeps him going, he reflects on a conversation he had with his mentor, Larry Leon Hamlin, who founded the National Black Theatre Festival at North Carolina Black Repertory Company. Hamlin told him that when white theatres stage Black-focused shows like Ain’t Misbehavin’, they have no real investment in the work beyond making money. Jacobs believes that part of the reason his theatre has been so successful is that diverse communities in Sarasota can see their culture reflected onstage, and they take pride in being able to support the work.

“There is no other part of society, no other culture, that is responsible for telling our stories,” Jacobs says. “It is our responsibility, and I feel very passionately that many of our white patrons also feel that.”

The origin story and the programming at Karamu House in Cleveland are a bit different. Founded as a settlement house for European immigrants in 1915, the theatre became a safe haven for African American artists when Blacks moved into the neighborhood for industrial jobs in the 1940s. The theatre’s name means “joyful gathering place” in Swahili, and in the past century it has produced everything from Langston Hughes to Vanessa Bell Calloway’s one-woman show Letters from Zora, as well as an original play, Believe in Cleveland, about the nation’s first Black mayor, Carl Stokes.

Karamu has seen its peaks and valleys, and when artistic director Tony Sias took the helm in 2015 the place was in need of a turnaround. Since arriving, Sias has patched relationships with funders and patrons, increased the theatre’s budget, spent more on marketing, and emphasized an investment in the quality of the art onstage.

“Quite often when organizations are in the midst of a turnaround, they cut back on production costs, but we invested more,” Sias says. “We are in a theatre-rich community, so we had to be competitive, and we have seen the return. We were at 73 percent capacity for our shows last season.”

Telling unique stories has been a hallmark of African American theatre since its establishment. It is not enough to put a Black Richard III or Mary Tyrone onstage; writing and producing original work and sharing that work with the community is an essential practice as well. This is part of what earned Crossroads Theatre Company in New Brunswick, N.J., the 1999 Regional Theatre Tony Award (which they have since donated to the National Museum of African American History & Culture). The theatre has presented almost 50 world premieres by African American playwrights in 40 years, including The Colored Museum and Spunk by George C. Wolfe and The Darker Face of the Earth by Rita Dove. Artistic director Marshall Jones III blissfully recalls looking down from the balcony and seeing real-life Tuskegee Airmen donning their red jackets during the 1992 premiere of Black Eagles, Leslie Lee’s play about their experience.

Now that the theatre is preparing to move into a new space in the fall and to announce the recipient of their first annual Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee Award, Jones is hoping they can revamp the associate artist program so that they are developing closer relationships with Black playwrights and Black designers.

“When artists of color work at predominantly white theatres, everybody walks on eggshells,” Jones says. “The white people walk on eggshells because they don’t want to say the wrong thing, and the artists walk on eggshells because they don’t want to offend the theatre. When you’re working at Crossroads you don’t have to walk on eggshells. It’s always about the work.”

Eileen J. Morris, the executive director of the Ensemble Theatre in Houston, started an initiative called “Celebrating the Creative Journey” to offer working artists a space, light technical support, and a small stipend to develop new plays. She is also invested in developing the next generation of performers through the theatre’s Young Performers Program, through which they offer theatre camps to students of all ages during the summer, spring, and winter break. In addition Morris is a recipient of a grant through the BOLD Theatre Women’s Leadership Circle, which the theatre has used to hire an associate artistic director and more female designers thus far. Morris will also be using part of the grant to work with a female playwright to develop a new holiday musical, because she says it’s hard to find shows that depict African Americans celebrating.

In fact the search for a multicultural holiday show is what connected Morris’s theatre to Young’s African American Shakespeare Company, where Young had created an African American version of Cinderella. Morris heard about the show and asked Young if she could produce it at her theatre too. It proved to be a runaway hit in both cities. Getting in on the ground floor with new work is a boon for most theatre companies because of potential royalties (and bragging rights), but for African American theatres, it is an essential way to have their communities represented onstage.

“I could name 50 Black theatre companies right now, and it’s important that all of us exist,” Morris states. “A few years ago we had a little girl come to see Cinderella, and on the program cover we had a picture of a Black Cinderella and she looked at her mommy and she said, ‘Mommy, she looks like me.’ That’s why we do it—so the young performers, teens, and adults can see folks that look like them.”

African American Shakespeare Company continues to run the show and occasionally updates the script, but in 2017 a dispute with their landlord at the African American Cultural Complex almost scotched the season. Determined to make it happen, Young called her connections at the ballet and the symphony, who agreed to let them stage their shows there. She sees this as a blessing in disguise, because going to venues with that kind of cachet allowed them to reach more audiences, and an advertising sponsorship from the Bay Area Rapid Transit meant that existing audiences always knew where to find them.

Few theatres own their buildings, and for African American theatres the numbers are even smaller (though three of the six theatres profiled in this article own their building outright). The insecurity of being subject to a landlord’s whims and fancies can make it difficult to plan ahead, commission new work, and make upgrades that will attract new audiences.

“One of my goals before I retire, and I don’t know when that will be, is for African American Shakespeare Company to have their own building,” Young says. “There’s no consistency about where we’ll be, and we have such a great following—300 subscribers and 10,000 single-ticket buyers during an average season. I have seen other theatre companies falter because somebody bought the space they’ve been performing in for 20 or 30 years and now they’ve been priced out of the market.”

That threat is what prompted Jacobs to purchase a building for Westcoast Black Theatre Troupe in 2013. Many African American theatres struggle because they don’t have connections to people in the inner circle of wealthy communities or benefactors who include them in their wills. They also face a gap in donor education, as many African Americans are accustomed to supporting church, politics, and education, not the arts. Jacobs recognizes that the Black community in his region is very small, which requires extra outreach.

“My theatre has been called ‘the miracle theatre,’ because it’s a miracle that white patrons are writing checks to support us,” Jacobs says. “In the beginning I was told that I would never get a $1 million gift, and six years later I got a check from a woman who gave the first seven-figure gift to our capital campaign. I was blown away when the white community eventually began to embrace us, because when we started they asked us why we even existed.”

Westcoast’s first executive director, Christine Jennings, is a retired banker who helped Jacobs find a building. While the Great Recession a decade ago was a challenge for many, it proved to be the theatre’s golden opportunity, as their landlord could no longer afford the former warehouse and sold it to them for $450,000. After Jennings’s retirement, Julie Leach took the helm and launched the theatre’s capital campaign to complete three phases of renovations on the space, which sits on 3.5 acres. They have raised $6.8 million so far, have already completed the education and outreach building, and plan to begin working on the theatre space at the end of this season.

“Black theatre in general needs more funding and recognition in the theatre world,” says Leach. She served on the theatre’s board before joining the staff, and has found that the theatre’s mission aligns with work she did as a social justice worker in her youth. During her tenure Westcoast’s budget has gone from $800,000 to $2.2 million, and the theatre currently has 5,958 season subscribers.

“African Americans must tell their own stories their way,” says Leach. “Diverse programming at other theatres often looks like diverse casting for a white story. But it’s not the same as a story written, performed, and directed by African Americans.”

Complicating all theatres’ fortunes is gentrification, and Black theatres are no exception. In Harlem, Houston, and the Bay Area, sky-high rents and property taxes are displacing longtime members of the communities many of these theatres create art for. National Black Theatre nearly faced foreclosure a few years ago but turned things around through a partnership with a major developer and an unrelenting commitment to serving the people of Harlem.

“When I inherited NBT, I inherited a resilient organization whose best practices had never evolved,” says Lythcott. “The Black theatre narrative is that we’re underserved, underprivileged, we don’t get the funding everyone gets, everyone’s racist. That’s not untrue, but it’s not bringing more resources to the table. Founders can sometimes get so stuck in the dogma of their struggle that they can’t see the opportunities outside of their struggle because they’ve beat the drum for so long.”

McCrory and Lythcott realized that there was a need to change the narrative to achieve fiscal health for the organization. Theirs is a story that many theatre leaders can relate to: Put simply, they went from a mentality of scarcity to one of abundance.

“We changed our narrative to say that Black theatre deserves to be funded because no one is doing anything as brave and revolutionary as this,” says Lythcott. “We spoke to the turn-on of Black theatre and the unique experience you get walking through our doors. Doesn’t everyone want to come sit at this table?”

And not all change is bad. For the Ensemble Theatre, the construction of a multi-million-dollar mixed-use complex and the expansion of public transit led to an Ensemble/Houston Community College light rail stop being built right in front of their building. Janette Cosley, ETH’s executive director, says that they get more convention groups and millennials walking through their doors because of the stop. She adds that as the neighborhood changes, the theatre is ready to embrace anyone and everyone interested in seeing African American stories onstage.

“The whole point of integration is not for us to disappear, but for us to have quality and equality wherever we are,” says Cosley. “Our theatre is for everyone—the ‘e’ in ensemble is for everyone.”

Securing funding is an issue for most nonprofit arts organizations, but for Black theatres the issue is much more complicated. Later in Wilson’s historic speech, he said that Black theatre is “alive” and “vibrant,” it just isn’t funded. That is still true today. In that same speech he posited that funders who support diversity initiatives, such as colorblind casting, at white theatres “have signaled not only their unwillingness to support Black theatre but their willingness to fund dangerous and divisive assaults against it.” African American theatres still face stereotypes about Black people mismanaging money and questions about the legitimacy of their programming. And as diversity trends upward, more funders are offering white theatres money for doing the same kinds of plays and education initiatives that African American theatres have been doing, usually without such largesse, for decades.

“A lot of major foundations invested in audience diversity at majority institutions, and a lot of those with means were welcomed at majority institutions, and as a result, minority institutions suffered,” says Sias. “It caused an exodus. That was a national trend, and minority institutions suffered, not unlike what happened to Black businesses during integration—everybody ran downtown and forgot about uptown.”

White theatres capitalizing on the potency of Black (and brown, Asian, Indigenous, et al.) stories is the elephant in the room of the American theatre. These major theatres get the funding to pay Black playwrights more to produce plays so they can prove to funders that they are investing in diversity. It’s a dysfunctional cycle that reflects the pervasiveness of white supremacy.

“White organizations are getting funding for doing what Black organizations have been doing the whole time,” says Young. “Foundations believe they are supporting the entire community with larger organizations, but they are doing a disservice to the smaller organizations that have been doing the work.”

Jones says that the drag-and-drop nature of just funding diversity when it comes from a majority white organization only heightens existing disparities. Value must be placed on the unique cultural perspective that can only be relayed to an audience when a work emerges from the community it is about.

“There’s a difference between Black theatre and a theatre with Black people in it,” Jones says. “Institutionally we bring a unique aesthetic. It’s great that Off-Broadway theatres are doing all of this diverse work, but don’t forget about us. I hope that audiences can tell that there’s a difference when they go to National Black Theatre versus Playwrights Horizons.”

Indeed a unique aesthetic is what has sustained all of these theatres over the years. Above all else the work onstage must be good, and there’s no better testament than the fact that audiences keep coming back season after season. These theatres have launched the careers of some of today’s hottest playwrights and most celebrated performers. The resiliency of Black folks and the flavor that permeates African American stories, conceived and performed by Black artists, are the draw.

“We must have a platform for the artists and for the diverse people of the world to have something to hold onto,” says Morris. “The stories are universal. I’ve seen Fences more times than I’ve seen any other play. I saw it in Germany and it touched their hearts.”

The African American theatre is as fertile and nuanced as the culture from which it is born. There is no separating art from issues of social justice, because to create or support art is to make choices about what’s important (and what is not). Aesthetics vary, resources are coveted, and different cities and communities bring different challenges, but it is imperative to have myriad narratives so that people of different backgrounds can learn about each other. There are never too many opportunities to hear a good story, and the one thing expressed by all the artistic leaders I spoke to is the desire to become the premier destination in their region to experience African American theatre.

“The state of Black theatre is something that can’t be positioned or serviced in a mammoth statement,” says McCrory. “It has to be uniquely analyzed and appreciated from the community in which it is housed in and navigating. In many ways it is the wealthiest space on this planet and in other ways it has a huge deficit. The real question is, how do we serve its uniqueness? How do we create systemic bandages that allow every institution to be served properly? It’s helping to hone the unique historical resource that our institutions provide and no one else can do.”

Kelundra Smith, an arts journalist in Atlanta, is a frequent contributor to this magazine.