Last December New York Times comedy critic and theatre maven Jason Zinoman was invited to give a speech at Shakespeare Theatre Company in Washington, D.C. The speech, reprinted here with permission, has been lightly edited.

I am honored to be here in my hometown at the Shakespeare Theatre, particularly because this is the last season of the remarkable tenure of Michael Kahn. He started running the Shakespeare Theatre in 1986, back when it was the Folger Shakespeare Theater, and I was 11 years old. I have written thousands of reviews in my lifetime, but the first one was for my high school newspaper, of a play here. It was a pan. So it’s generous of him to let me back in the door. Throughout my childhood, my parents took me to see Shakespeare here, and on the car ride to the theatre my mom would explain the plots so I would not get too lost. The productions I saw here were exciting, dynamic—the complete opposite of the stodgy work that a kid imagines Shakespeare plays to be. To be exposed to top-flight productions of the greatest writer who ever lived is formative. It matters.

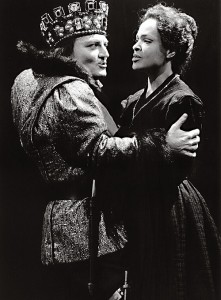

Great art you see as a kid sticks with you in a way that art you see as an adult does not. To take one example, Michael Kahn directed a production of Richard III with Stacy Keach in 1990 that ruined every subsequent Richard III for me. Ian MacKellen, Kevin Spacey, Peter Dinklage, Mark Rylance—they all pale next to my memories of Keach. This is a testament to the production and performance, but also a function of me having been young. I recently looked up the review of the play in the Washington Post and found this description of Keach from then-critic Lloyd Rose: “With his open-faced smile and amiable laugh, he seems positively jolly—in his frequent asides to the audience—as he goes about eliminating rivals, betraying confederates, and turning the truth on its head. Keach adroitly conveys Richard’s tortured duality of preening narcissism, covering both his arms with celebratory kisses after his conquest of Lady Anne.”

This reminded me of something about that performance: It was funny. Not just funny for Shakespeare, but real laughs from the gut. Keach was a terrifically charming villain, a seducer who was constantly in the action and outside commenting on it at the same time; and the cast, including the brilliant comic actor Floyd King, captured the hilarity in the horror of this play. Shakespeare can be one of the best and worst arguments against the idea that comedy ages poorly, but this production represented a strong case against it.

This gets to the subject of my talk here. I was asked to discuss the state of comedy. I was happy that the request was a bit broad because it gives me flexibility, and apologies that this talk will veer more into the state of theatre. But they are related.

Let’s dispense with the short answer right off the bat: The state of comedy is gangbusters. There were more specials released in 2018 than any year in history; they were artistically ambitious; the director of the standup special, long a job for anonymous craftsmen, has suddenly become a prestige job; comedians have a higher cultural status than ever; Trump has boosted ratings for late night hosts and “Saturday Night Live.” What comedy has also proven of late is that it can stretch itself. It is perfectly suited to dig into the deepest, thorniest, darkest issues. Hasan Minhaj is doing very dense political humor. Drew Michael probes the darkest thoughts about art and love in a standup set. Look at comics handling of #MeToo: No art form has dug into this as fiercely and often, with the work of Liza Treyger, Cameron Esposito, Ted Alexandro, and Dave Chappelle providing a true diversity of points of view.

The biggest comedy event of the year was Hannah Gadsby’s Nanette, which is some ways an attack on comedy itself and its ability to be honest, to challenge power, to do good. As a critic, I see harsh criticism as a sign of comedy’s health. Gadsby has been a monumental success, and you know she a monumental success because now everyone seems to be criticizing her. This is what happens when you are successful. And in 2018, when the media cycles spin so fast, if something is hailed half a year ago, people have already gotten sick of them.

So what are the criticisms of Hannah Gadsby? Some take issue with her arguments about self-deprecation being damaging for marginalized communities as opposed to being a tool for them. Some say she’s not funny. But the most common criticism, one you hear all over the place, is this: It’s not really standup comedy. So what is it? It’s a solo show. It’s not standup. It’s theatre. It’s telling that a comparison to theatre is an insult. It reminds me of when political journalists use theatre criticism as an insult, as if what you read in Politico has less substance than what is in Style section.

I found the fact Hannah Gadsby doesn’t just want laughs to be wonderful, and her ambition is evidence of a form expanding its reach, diversifying. But there’s something else going on with this criticism. Nanette actually does seem a little like solo show from an earlier era, the kind we saw in the 1980s or ’90s. But many of the artists who worked in that genre are now doing comedy more than theatre. Gadsby represents a larger co-optation of the theatre by comedy.

This brings me to my main argument, which is a message to the theatre: Comedy is, if not your enemy, then at least a very formidable rival.

TV was long seen as the enemy of theatre. A common criticism you would often hear of a play is that it was too much like a sitcom. But TV was always fundamentally different than theatre. Comedy, on the other hand, shares a lot. It is a live art form, and the same romantic defenses you often hear of theatre you can also hear from comics—the beauty of its ephemerality, the present-tense nature of the form in a time when everyone is on screens. People who once went into the theatre are now going into comedy.

Since I saw that Richard III the arts world has radically changed. Back then the solo show was a thrilling art form, with artists like Eric Bogosian, Karen Finley, Spalding Gray, Whoopi Goldberg. You had people in the theatre like Danitra Vance, one of the first African American women to turn theatre work, solo shows, into spots on “SNL.” Think on that: Theatre was once a springboard to “SNL.” No more. Comedy institutions have a stranglehold on the pipeline. Mainstream standup used to be jokes about airplane food—Seinfeld, Boosler, all great stuff, but it was a narrower art form, while theatre was broader.

In the ’90s, I covered experimental theatre in New York City: The Wooster Group, Richard Foreman, Richard Maxwell. I see echoes of those artists in the work of people like Reggie Watts, Eric Andre, Kate Berlant, or the many Andy Kaufman-inspired artists. Some of the most gifted young comics working in New York today are musical lovers who incorporate songs into their act, blurring the line between comedy and cabaret. On Broadway the hottest comedy of the fall was a show by a comic, Mike Birbiglia.

The biggest change has been in the training: The rise of improv schools has radically changed the culture. The people who once went to Juilliard are now going to Upright Citizens Brigade (UCB). People who once learned the Method are now learning “Yes, and.” This has a major impact on the culture in ways I don’t think anyone truly comprehends yet. It has an impact not only on artists, on the kinds of things they know and the skills they develop, but much more broadly on how people see comedy vs. theatre. I can’t tell you the number of people I work with at The New York Times who have taken improv classes or who moonlight as standups. My 10-year-old just learned about improvisation in 4th grade at a New York public school. While the worldview of the theatre is becoming increasingly remote, the worldview of comedy is common, the lingua franca of ordinary life.

One last piece of evidence of comedy moving into theatre’s territory I have to add is myself. I grew up immersed in a culture that venerates the theatre, and which is sometimes dismissive of other forms. I went to the Shakespeare Theatre. I went to my mother’s theatre, Studio Theatre, on 14th St. I did not go to the comedy club on 14th St. where Dave Chappelle and Patton Oswalt got their start. I wish I had! But to a kid soaked in the theatre, it was not a place I even considered going. My career stumbled into theatre journalism but it stayed there because I loved the theatre, and I wanted to cover it. But the theatre press vanished. The jobs left. Meanwhile jobs in the comedy press have grown.

Some of comedy’s success is simply due to ticket price (it’s usually much cheaper than theatre) and scale. A comedy special on HBO reaches more people than any show at the Roundabout. But that’s no longer quite as true as it once was. NT Live has shown that theatre can be live while also going global. Netflix has put Broadway shows Oh, Hello, Latin History for Morons, and Bruce Springsteen on its platform. Taped theatre is not the same as live theatre, just as taped comedy is not the same as live comedy. In both cases something is lost, but that is different than saying everything is lost and nothing is gained. Theatre, like comedy, can go digital without abandoning its soul.

But the main thing that theatre can do to push back against the encroachment of comedy is to produce more work that makes people laugh. You are attempting it here with David Ives. But where I live, in New York, comedy is a very small part of the theatrical menu. It’s rare that a major production is a comedy. I can’t remember the last time I saw a romantic comedy. There are 10 mediocre Off-Broadway plays about serious issues for every mediocre play that primarily wants to make you laugh. It’s even more rare that a major revival is a comedy. We regularly produce Mamet and O’Neill, but rarely Neil Simon. It’s crazy to me that there was only one non-solo show play on Broadway this past fall that could be called a comedy—and it’s from England. Even when Broadway directors adapt biting satires, like Network, the work is transformed into a mirthless tragedy.

In October a group of theatremakers who had worked in comedy with a grant from the Mellon Foundation met in Boston to talk about why comedy is so scarce. HowlRound recorded the results, and they include a list of reasons for the bias against comedy in the theatre, which include: 1) Skepticism that comedy is important, 2) Not trusting silliness, 3) The criticism that something is “sit-commy,” 4) Too many artistic directors with no sense of humor.

Let’s put aside the last three, all of which hold some truth, and focus on the first. If the comedy world today has taught us anything, it’s that comedy is just as likely if not moreso to speak to important issues. That is what is in vogue now. I’ve seen standup on mourning, depression, white supremacy, misogyny, loneliness, love. If you can get people to laugh, you can dig into the darkest, weightiest, most complex subjects in the world. Steering clear of comedy means you are steering clear of the biggest challenges that art can take on. Just as comedy has moved into dark territory, just as it has become serious and sometimes dour, theatre should embrace comedy and jokes and joy.

Not embracing comedy, to be clear, also has commercial implications. One of the most successful theatre troupes on the West End in London to emerge in the past decade is the Mischief Theatre, which produces broad, smartly done comedies. They are known for The Play That Went Wrong, but they’ve produced three plays on West End—none that have matched the success of The Play That Went Wrong but all of them successful.

This brings me to the main reason you should program more comedy. Right now your audience wants, perhaps needs to laugh. And you shouldn’t ignore the audience. Shakespeare didn’t. Michael Kahn’s Richard III is a great example of a bloody history play co-opting comedy. That reached audiences, including a kid who saw the possibilities of Shakespeare and the theatre three decades ago. I hope many more are as lucky as I was. Thank you for hearing me out.