Thirteen years ago, The New York Times ran an article titled “Why Female Directors Are Broadway’s Smallest.” The headline referred not to their height but to their scarcity: At the time, out of the 39 shows that opened on Broadway in 2005, just three were directed by women. To figure out why there was such a large gender gap, the Times interviewed a number of well-known producers, as well as a young, up-and-coming female director named Leigh Silverman, then making her Broadway directing debut with a play called Well, by Lisa Kron. At 31 years old, one of the youngest women to have directed on Broadway, she gave an answer that contained a veteran’s insight.

“Producers are looking for a director who is a strong, stable captain of their ship; a proven commodity that they believe will minimize their financial risk; and a leader who will weather high anxiety while staying creatively dexterous—traits generally thought to be associated with men,” she told the Times. “Unfortunately, women across the theatrical disciplines (producing, directing, designing, writing) are still prying the door open.”

Little did Silverman know, 13 years later, she would be one of the few female directors to consistently work on Broadway. When I emailed the article to Silverman and asked how she feels about having talked about gender equity for most of her career, she responded with characteristic good humor: “This is my life’s work, I know it. Yay?”

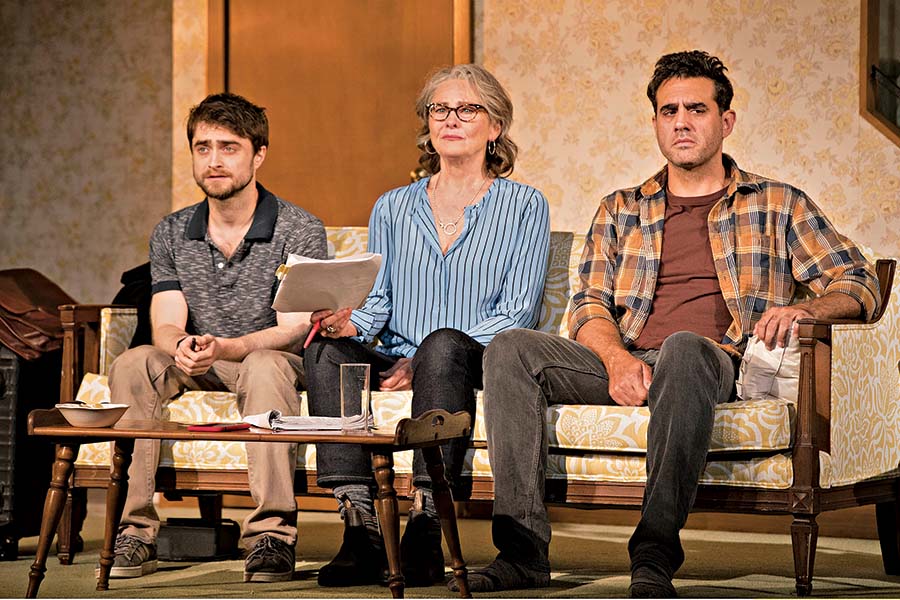

Since Well Silverman has directed on Broadway three more times: Violet, Chinglish, and this season’s The Lifespan of a Fact. On the last show Silverman made history by putting together Broadway’s first all-female creative team. Speaking at a panel in December, alongside designers from Lifespan, Silverman said her choices in creatives were very intentional. “One of the things I felt was important was—in a play written by three white guys, based on a book written by two white guys—I bring on a lot of women. And also they were women who were diverse not only racially but in terms of age and experience,” she said to the predominantly female audience.

So making history “was an accident,” the moderator ventured. Said Silverman, with a hint of incredulity in her voice, “It wasn’t an accident, because I meant to do it. The accident is the patriarchy, not the design team.” The room erupted in applause. “I just went for the best people I knew. Bam!”

The list of frequent Silverman collaborators is impressive: Kron, Jeanine Tesori, David Henry Hwang, Ethan Lipton, David Greenspan. And Broadway isn’t her only playing field: In addition to Lifespan her directing credits this season include the Off-Broadway stagings of Wild Goose Dreams by Hansol Jung at the Public Theater and Hurricane Diane by Madeleine George, another frequent collaborator, Feb. 6 to March 10 at New York Theatre Workshop (in a co-production with WP Theater).

That’s par for the course: In any given year Silverman will work on five to seven shows. On the day we met for lunch in New York City in early December, she had come from meetings with composer Shaina Taub (about a suffragette musical), and with Hwang and Tesori about Soft Power, a meta-musical about U.S.-China relations that features Hillary Clinton as a character. Soft Power got universal praise when it played last year in Los Angeles and San Francisco, and Silverman considers herself “optimistic” that it will arrive in New York in the fall.

It’s just more shows on a long list of credits for Silverman, who moved to NYC in 1996, and has collected two Obies and a Tony nomination in the decades since. “Someone was like, ‘You’ve done 40-something new plays in New York,’ and I was like, ‘How did that happen?” she said with amazement.

From May 2010 to April 2017, according to a study released by the League of Professional Theatre Women, Silverman was the most-employed female director Off-Broadway, with 15 credits to her name (and overall, female directors were only hired 34 percent of the time in seven seasons). So chances are if you’re reading this piece and you attend theatre in New York with any kind of regularity, you’ll have seen multiple Silverman productions. “She’s the hardest-working woman in show business,” enthuses Hwang, who has worked with Silverman on five productions.

You can’t pinpoint a Silverman “style,” and she wouldn’t call herself an auteur. Instead she’s like Mary Poppins, reaching into her vast toolbox to find the best thing that will serve the play at hand; actor Cherry Jones calls her “a great schoolteacher who doesn’t need to discipline.” It can include spotlights and roving set pieces to denote memory in Well; projections and glass screens giving way to a couch play in Lifespan; a rotating turntable in Chinglish. “No two shows really look the same,” agrees Kron. “She masters so many different kinds of work.”

To Kron, who met Silverman in 1998, the director’s biggest talent is storytelling. “She has complete respect for the writer’s process, and authorial autonomy,” says Kron. “She excels at asking the right questions to open a door to the next thing and the next, helping the writer to get to the heart of whatever they’re after.”

Her facility is not only with writers, according to Jones, who Silverman directed in Lifespan. “The way she works with actors is unique to my experience,” says two-time Tony winner. “She really gives you a tremendous amount of room to play, and always manages to drop in what you need to hear and what you’re most missing in such a way that you hardly even know you’ve been given that direction.”

Prior to Lifespan Jones had rarely done comedy, and she remembers struggling with how to set up and deliver a joke. “I said, ‘Leigh, I know this part is meant to be funny.’ And she said, ‘None of it is meant to be funny. You don’t have to think about that. There’s nothing but the truth and reality of the moment.’” That was a light-bulb moment for Jones, who has garnered critical praise, and raucous laughter, for her performance.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Silverman lives and breathes theatre. It’s not just the aforementioned busy work schedule; it’s that when she speaks about the craft, she seems to surge with electricity and endless amounts of energy.

“One of the things that I love about theatre is you have these great ideas about what you’re going to do, and it’s just nothing but problems,” she explained over sushi. “I always say it’s like ‘Project Runway’; I’m gonna make this amazing thing, and literally it’s nothing but problems. And that…” She pauses, searching for the right word. Tension? “Yeah!” she exclaimed, lighting up. “I like that. I like the challenge of that.” She then shrugs. “I dunno, I guess I like things that are difficult.”

When looking for projects, she looks for collaborators with that same energy and knack for problem-solving. “I am so attracted to writers who have an inexhaustible need to be better and to keep going,” she said. Silverman may describe her collaborators as inexhaustible, but that’s also an apt word for herself.

And while there is not a Silverman style, there are certain thematic territories she likes to explore. The impulse came early. When Silverman was 17, she directed a play for her local high school called Compromised Immunity, about men living with AIDS. Because she was, in her words, “precocious,” and a bit “bossy,” and because it was 1992 in the middle of the AIDS crisis, “I was like, ‘This is the play that my high school needs,’” she said, fondly recalling her own gumption. “I had the captain of the lacrosse team play an AIDS patient with a terrible English accent. I was full in. We were drawing lesions on with Sharpie.” She then adds dryly, “I’m sure it was terrible.”

During her childhood in Washington, D.C., theatregoing was a regular pastime for the Silverman family. Her dad was on the board of Arena Stage, and her stepmom was on the Theater J board. At 17 Silverman already had her sights set on being an artist, with a savvy and intelligence beyond her years. For Compromised Immunity she invited local artistic directors and critics to come see it. Among those in the audience was Howard Shalwitz, who was running Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company; he gave her her first professional critique.

“He was like, ‘You did a fine job with the play—it’s not very good,’” she recalled. Still, he praised her choice of material, telling her, “It’s really important that you picked this play to do. And you’re an artist that I’m gonna want to work with.” Sure enough, Silverman did eventually direct at Woolly Mammoth (Jump/Cut by Neena Beber in 2003). (When reached for comment, Shalwitz said, “Leigh’s work with the actors really stood out. She was precociously articulate and passionate in talking about it.”)

And true to form, after graduating with dual degrees in directing and playwriting from Carnegie Mellon, Silverman’s first job out of school was as a production assistant on the Rent national tour. “At that point being a PA on the Rent tour was the equivalent of making it, I just was like, it will never get better than this,” she said with a laugh.

If there’s a connecting thread among Silverman productions, it’s that they are often stylistically adventurous and feature stories about outsiders. “I think Leigh feels comfortable with working on material about otherness, and things that are outside the mainstream,” remarks Hwang. “She has a lot of cultural competency, she has a lot of sensitivity. It’s important for her work to be meaningful in a sociopolitical sense.”

She brings this sensibility even to presumably mainstream work. In 2016, for example, Silverman directed a version of Sweet Charity Off-Broadway starring Sutton Foster (another frequent collaborator) that was pointedly darker than previous versions, with a Charity who gets steadily less bubbly as she begins to realize that happily ever after won’t come when she finds a man but lies within herself. When asked about this impulse toward complication, Silverman explains that as an only child whose mother died when she was 13, she remembers her early life as “profoundly lonely. I think I spent a lot of years feeling on the other side of the looking glass from the rest of the world. And I’m sure being Jewish had a lot to do with it; I’m sure being gay had a lot to do with it.”

And being a woman. In our two-hour conversation, Silverman frequently touched on the different expectations placed on women versus men in the theatre, and in wider society in general.

“It’s been interesting about this all-female design team thing, because it’s actually forced people to look,” Silverman remarked. She thinks the high stakes of Broadway have something do with it, as “it’s historically been that the closer you get to money, the fewer women and people of color there are.”

Silverman is frank about one reason she’s able to work so often and to have built the clout she has: because she actively prioritized work at the expense of “financial stability, career stability, mental health,” she said, listing them without hesitation. “There’ve been so many life events that I’ve missed because I’m in tech. It’s hard when you think about the compromises you make and what’s on the other side and is it enough? And certainly those are the questions that keep me up at night. Is it really worth it? What’s the point? I feel like I’ve sacrificed so much to have this career, and is it a good trade-off? Some days the answer is really yes and some days I’m not so sure.”

A few years ago, she told me, she had a “mourning period” when she realized that she could not afford to have children (“Working Off-Broadway, while it’s my dream come true, is not particularly lucrative”).

But what makes Silverman a force in the American theatre isn’t just her artistic drive or her honesty about details normally covered by a curtain. It’s that she is constantly asking questions. She opens her eyes to problems and reevaluates what she can personally do to contribute to a solution. For her creative team for Lifespan, she made sure there was a private lactation room for new mothers and a supervised play space for the kids. “I just think you shouldn’t feel like kids are a liability to your career,” she said.

After realizing a couple of years ago that her “life’s work” of advocating for more women in the theatre wasn’t sufficiently intersectional, embracing a full spectrum of difference, she decided, “I never want to be in another room I’m in charge of where there’s only one of anybody.” As someone who always felt like she was on the outside looking in, Silverman wants to make her own spaces welcoming. “Every decision that we make profoundly speaks for who we are and what we believe in, and nothing feels casual.”

If that sounds like a killjoy attitude to some people, Silverman will have you know that she’s aware. She did make her career on being perceptive. “I feel like it’s because I’m a Sagittarius,” she said with a smile. “There’s a thing for Sagittarians about injustice—we don’t like injustice. I think it’s where some of my delightful self-righteousness comes from.”