The following essay first appeared in A World Without Cages, an online collection of prison literature from the Asian American Writers' Workshop. AAWW is a national literary nonprofit working at the intersection of race, migration, and social justice. The author, Elizabeth Hawes, is an actor, gardener, playwright, poet, and prisoner in Minnesota. She has received three national Prison Writing Awards and one Fielding A. Dawson Award from PEN America.

7:02 a.m. 6/18/2017 Second day working at the gym in the only women’s prison in Minnesota. I work out of what used to be a small 8’x12’ cement-tiled storage room. It contains 4 large bouncy balls, 90 workout videos from the mid-’90s, hand weights, yoga mats, and a lot of cleaning supplies. My co-workers are:

- Martin, a transgender man who will be free in November and will be sent back to Mexico even though he has lived in Minnesota all but the first two years of his life.

- Smokey, a woman with an eating and exercise disorder.

- Ava, a woman with a personality disorder who will be leaving in October to finish out her time in a federal prison.

The first two, Martin and Smokey, love each other. Actually, it is more complicated than that: They love/hate each other. Their relationship involves a lot of swearing and jealous glances.

All three work out constantly.

Throughout my day I often ask myself what I am learning or bearing witness to by being where I am. What is in front of me and why. I frequently have no answers to my questions.

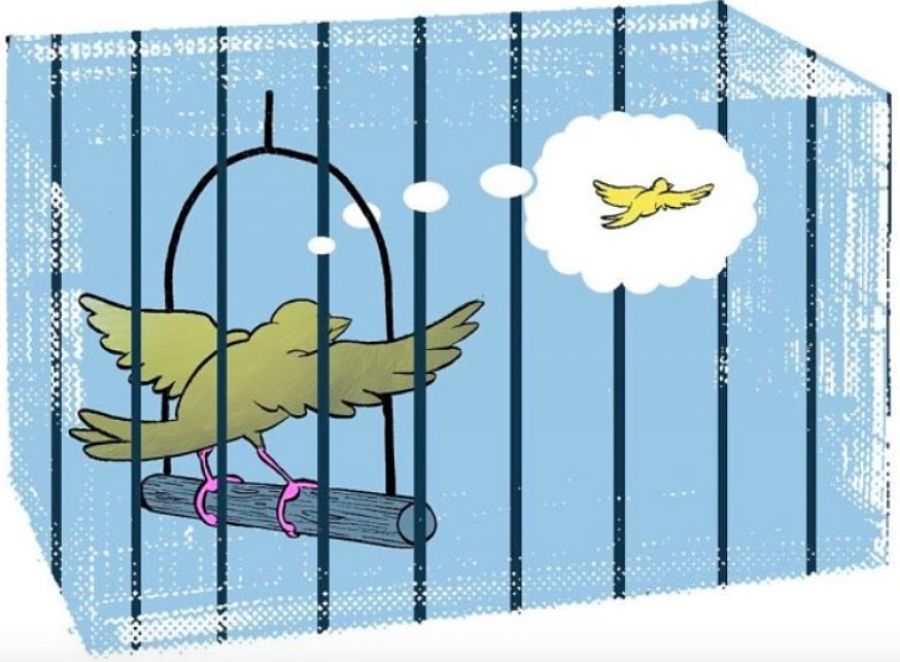

I think about safety vs. freedom. We are frequently told we are here for our own safety. For a certain percent of the population that is probably true, especially for people suffering from addiction. Personally, while I object to drugs or drinking if someone is impaired behind a wheel and could hurt others, I think that adults should have the right to do what they want in their own homes.

My guess is that 95 percent of the prison population would choose freedom over just about anything.

1:00 p.m. 6/22/2017 Martin and Smokey are fighting. Smokey tells me that she has had food issues (bulimia) since she was 12, has 5 tattoos, and only shampoos once a week. She also says that her hair smells like feet. I keep my distance.

I spoke with a staff member here once about addictions. She said that in her opinion eating disorders were the most difficult to contend with, because you couldn’t just avoid food like you can drugs or alcohol. Everyone has to eat.

4:15 p.m. 7/17/2017 One of the perks of working in the gym is that we get paid to work out. I elliptical next to a Hmong friend. She is in fantastic shape and plays a competitive game of volleyball, basketball, and, when it is offered, softball. She is 4’10” and 59 years old. No arthritis. Super limber. Runs five miles at a pop. I don’t have the knees or the will.

I am not Hmong-tough. My Hmong friend survived in the jungle for a year with no food. She and her husband ate bark and leaves. When her body stopped producing milk, she watched as her baby starved and died. My Hmong friend survived in a refugee camp in Thailand with 6 small children for 10 years. When I hear about her past, I understand how easy a sport like volleyball must be after surviving a war in Laos.

12:15 p.m. 7/30/2017 I mop the gym floor. This involves:

- Sweeping the floor with a large, flat dust mop. (I am always amazed by the amount of lint I sweep up. Every day the lint pile is the size of a Norwich terrier. A fuzzy, grayish-purple Norwich terrier. The air vents above the gym are large—about a yardstick wide—and I would be scared to see how much lint is amassed inside them, to know what I am breathing in all day.)

- Filling a wet mop bucket in the hallway closet and rolling it back to the gym.

- Putting up yellow plastic signs that say “Danger: Wet Floor.”

- Mopping around women who are following along to exercise tapes at one end of the gym, and around Smokey, who is pounding out the Insanity Workout tape by herself in the middle of the room.

- Emptying the dirty water in the hallway closet and rolling the empty bucket back into the gym.

I spend the rest of the afternoon talking to Martin. I have gay friends coming out from all directions, but I have never had a trans friend.

Can I ask you something?

Sure.

Do you have to go to Mexico when you are released?

Yes. But I’m fighting it. I haven’t been in Mexico since I was two. It is not my home. I’m from Bloomington.

I’m sorry. Do you even know anybody there?

My parents live there now, in a small town close to the border.

Do they know you as Martin?

Yeah. They’ve always known. Always have supported me. My family loves me for me, you know?

I’m glad. Some of my gay friends have had very stressful coming-out experiences. Most waited till their early 20s, and told their mothers first, crying, saying they had something really important to tell them. And their mothers were like, “What happened? What’s wrong?” And when they said that they were gay, the moms were like, “My God, the way you were crying I thought you killed someone.”

I used to cry when I had to wear a dress. I had this uncle who would come over and bring me clothes, girly clothes, and I would hide in my room so I didn’t have to put them on.

I think back to my time working at the Unicorn Theatre in Missouri, which produced work by gay playwrights. The space was small and oddly shaped; the audience was literally two feet from the stage. This was in the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Gay people were dying, suffering, and isolated. I was performing in a series of one-acts, and I remember one set in New York City during the apocalypse of AIDS. During one of the performances, as I was delivering a line about purple-splotched skin, I looked out to the front row, and there was a man with purple splotches on his skin.

Until that moment, my theatre work was more about establishing a good résumé than human connection. That moment made everything real. It woke me up. Hey! This is someone’s life, not words on a page. This man in the front row was dying, and he came to see this show that reflects his experience. Make it worth his time.

7:09 a.m. 8/02/2017 Smokey has obviously been tanning and is now the color of stained wood. (By tanning, I mean prison tanning—i.e., wearing gray shorts and tees with socks rolled into shoes, sitting on cement benches, smearing oil-based hair products on your skin, and baking.) She came to the gym to work out to an Insanity tape, which she did for about two and a half hours. Meanwhile I talked to the new gym supervisor about theatre in Minneapolis. We discover that she is a fan of the traditional musical. I am a fan of improv and accordion music.

12:09 p.m. 8/12/2017 I work with Ava, who, as we fold rags, tells me that she also has an eating disorder and gender issues. She tells me that she is working on a letter for the parole board. I tell her that I helped another woman write a successful letter last spring and will help if she would like. She would.

I talk with Martin.

Has it been weird being here as a guy?

Yeah. They make you wear a bra or go to segregation. And I’m not okay with that. The underwear policy is bullshit. You can order compression bras if you fit the “criteria,” but not everybody does.

I had never thought about that. That would suck.

It makes me feel sick to wear women’s clothes.

I understand. I mean, I don’t understand, but I understand.

8:46 a.m. 8/24/2017 Smokey with her walnut-colored skin tells me that she likes the egg salad at the chow hall because it gives her diarrhea. She tells me that women here don’t like her because she is so good-looking. I silently debate whether to tell her that women don’t like her because she is rude and unfriendly and treats people poorly. I don’t say anything. Martin is my favorite co-worker.

He leaves tomorrow. He is being transferred to Sherburne County Jail. I remember Sherburne; I was housed there for about six months. It’s federal, and ICE deports people from there. I remember it as cold, and on the mornings I left for trial, I saw rows of cheap plastic chairs filled with young handcuffed Latinos. They were wearing working-man clothes. They looked kind. I felt bad. It was depressing.

4:09 p.m. 9/27/2017 Work is cancelled, but I still have to take photos in the visiting room. To get pictures, people buy service tickets from the canteen for 50 cents apiece, or visitors can buy them in the lobby for a buck. We offer two scenic backdrops: One is an abstract of red and pink splattered paint, and the other features a child-like drawing of a tree, sun, and clouds. People can also opt for the cement brick wall.

1, 2, 3—Cheese!

I sit in a small, glass-encased room until the visitors get acclimated to their person. I usually give them about 15 minutes together. Sometimes I wait longer if a conversation seems intense or emotional. I like to give people their space. But it is a controlled visit, with a guard in the room, and we can’t make contact with visitors except a brief hug and kiss on the cheek. We have to sit facing the guard and can’t get up from our chairs.

Parents and lovers and children and religious volunteers are the regulars. The people who show up no matter what. Four o’clock Wednesdays. Six o’clock Fridays. Early morning Sundays.

It is here that we talk and laugh and love without touching.

We sit two feet apart across from the visitors, unless they are a kid. If you are a kid, you can sit next to your mom.

1, 2, 3—Please!

Before I snap my photos, I give a speech: “Please take off your badges, please do not touch, please face forward, please no hands on hips.” Then I give my big line: “Please give me a smile.”

After the pictures are taken, I go back to my small glass room by the door and am forgotten. But then I see what no one else sees: the faces as they leave. As they turn away from the woman they love and are now leaving in prison, I see the weight of the suffering just beneath their eyes. They try to keep it together. They’ll often turn and give a final “hang in there” wave before they go out the door.

I assume they wait until they get to the car to cry.

3:05 p.m. December 16, 2017 I hear that Martin was sent to Mexico.

Are you scared of being who you are in Mexico?

If other people found out I would be killed. No question. The place where I would be shipped to has the highest rate of violence against trans people in Mexico. It is dangerous.

How will you stay safe?

I am going to lay low. Stay with my parents. Hopefully come back soon and go up to Washington state, where my sisters live. They work in the orchards, harvesting and trimming apple trees. I’d like to come back in a few months and work with apples.

You are the hardest worker I know. You are bilingual. You have a GED. People should want to hire you!

Let’s hope so.

My hope is that Martin is soon back on the West Coast, picking apples. I like to think he is, with his leg hair blowing in the wind.

2:25 p.m. 2/24/2018 I hear that Ava had success with the parole board and is back home.

I think about Martin.

You look and act like a guy. You are a guy. I don’t think that anyone would think otherwise if they were to meet you. I hope this will protect you. I hope that you will be safe until you can come back. I wish you didn’t have to leave.

I’m excited to be released from prison. To be free. The rest we will have to see.