A group of young men rehearsing How the Grinch Stole Christmas are debating how best to block the moment where the Grinch shoves the Christmas tree up the chimney. Brad*, who is playing the tree, simply hops offstage, but Justin, the Grinch, thinks this a poor choice.

“You’re a terrible actor,” Justin says bluntly. Brad protests.

“Everyone is doing great,” interjects Rachel Tibbetts, who is directing the show (actually more of a staged reading). The other young men onstage are playing the narrator and Cindy Lou Who—the 2-year-old girl who catches the Grinch stealing her tree—while two other young men work on a song to go with the performance.

Tibbetts reblocks the scene and it works. The guys run through it again before leaving the stage and lining up at the back of the gym.

Inside the sunny gymnasium, the boys are dressed in jeans or basketball shorts and T-shirts on an unseasonably warm November day. This could be mistaken for a rehearsal at any high school, albeit an all-male one. But then in a flash it reverts to its original setting, and the young men wait to be escorted by three chaperones to their next activity. This is the Hogan Street Regional Youth Center, a juvenile correctional home in the city of St. Louis. Rachel Tibbetts comes here every Thursday afternoon as part of the Prison Performing Arts program to teach incarcerated youth about theatre, literature, writing, and even playing the guitar.

“I think that art has this kind of transformative power that a lot of other things don’t,” says Tibbetts, director of youth programs for Prison Performing Arts. “A 30- or 45-minute performance can change you.”

Tibbetts describes her program at Hogan Street as “process-driven.” The students watched The Outsiders and wrote about topics brought up in the film. They read To Kill a Mockingbird and discussed how it might be staged. They did improv and watched local actors perform scenes from Of Mice and Men. The emphasis isn’t on performance per se but on teaching students how to learn.

“You’re learning focus and concentration and listening skills and literacy skills,” says Tibbetts. “You learn about empathy, and you learn how to collaborate with someone. We have to give people opportunities to try and grow as individuals while they are locked up. ’Cause you don’t want people to go back [to prison].”

Soon another group of boys files in. Hogan Street inmates are divided into three teams: Spartans, Vikings, and Titans. They rarely interact with each other, and certainly couldn’t collaborate on a play. So Tibbetts has divided The Grinch into three sections, one for each group. In this group the young man playing the Grinch, David, has hurt his voice and his knee. Another boy in the group, Harold, who doesn’t have a role, offers to read the Grinch’s part. He bounds up to the stage.

The kids who aren’t participating agree to be audience members and let the students onstage know if they’re being loud enough. When there is any teasing—because an actor mispronounces a word, say—Tibbetts cuts through it with cheerful enthusiasm, saying that everyone is doing a great job. What’s striking is the chemistry in each of the groups. The boys seem to get along, more or less, and aren’t self-conscious about putting on funny voices, pretending to be 2-year-old girls, or dressing up as Christmas trees in front of each other. This may in part also be attributable to Tibbetts.

“I first met Rachel when I was in a juvenile center and she did a lot of group building exercises,” says Justin. “A lot of [inmates] have this idea that ’cause we’re in jail we should be doing this or that, and there’s a lot of negative thoughts that we can’t have a good time and get along with each other. She comes and changes that. She interacts us together, and people that you never think would do something like that would actually participate.”

David, who recovered sufficiently to be able to play the Grinch on show day, agrees. “We are just being there for each other, so even if you mess up, no one takes it too seriously. You’re just having fun with it, so you won’t be really embarrassed or nothing like that.”

Tibbetts’s program creates a “safe space” in the best sense of the phrase: It gives the young men a chance not only to take a risk, but also to support their compatriots while they take risks. “It’s an opportunity for young people who have been forced into a very adult situation, in a lot of ways, to just be playful,” Tibbetts says.

“When I was a child, I was in a lot of performances,” Justin recalls. “I remember when I was in fifth grade, my school performed at the Fox Theatre. Then over the years when I started following down a negative path, I forgot all about that. But then when I came here and started doing the little program with Rachel, it kind of brought me back to the other side. Like yeah, this is what I used to do.”

Prison Performing Arts may be best known as the subject of a 2002 episode on the radio show “This American Life,” when founder and then artistic director Agnes Wilcox was staging the fifth act of Hamlet. Wilcox was known around St. Louis: She’d taught at Webster University, Washington University, and founded the New Theatre. In the 1990s she founded Prison Performing Arts.

“Agnes was a little bitty woman with short, cropped gray hair, and she always wore black, right?” says Brat Jones, who joined Prison Performing Arts in 2000 while he was incarcerated at Missouri Eastern Correctional Center in Pacific, Mo. “And it was also like she was the neighborhood mafioso, cause she had this aura of power about her. She was so gentle and nice, but then there was always that tenacity, that go-getter attitude of never say no. She pushed us.”

Wilcox pushed herself too, expanding Prison Performing Arts to work with juveniles, and then, in 2005, to form an alumni company for released adults who had been through one of PPA’s programs at Missouri Eastern, Women’s Eastern Reception Diagnostic and Correctional Center in Vandalia, Mo., or Northeast Correctional Center in Bowling Green, Mo.

Wilcox, who retired in 2016, died unexpectedly in 2017 and now Christopher Limber serves as PPA’s artistic director, overseeing the adult prison programs and the alumni company. Tibbetts joined PPA in 2005, and despite knowing about the alumni company, hadn’t brought them in to perform for the juveniles until recently, in the fall of 2018. “It was a performance 13 years in the making,” she quips.

Rehearsal doesn’t seem to be going well the night before the PPA Alumni Theatre Company perform at the St. Louis City Juvenile Detention Center. They’re rehearsing Midsummer Madness, an adaptation of the rude mechanicals’ play from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Jones is having trouble remembering his lines, and everyone seems to be dragging, except for Damien Chambers.

“We need to pick it up in here!” he exclaims halfway through rehearsal. Everyone laughs. “I’m for real.” It’s not surprising that he’s the newest member of the alumni company, having just been released from prison in August after more than a decade behind bars.

“I’m just excited,” Chambers tells me later. “I’m too excited for the room. We’re all out here and it’s like when I was doing this in prison, I imagined doing it on the streets and having this opportunity.”

Chambers remembers his involvement with PPA as a kind of lifeline. “I could be whatever I wanted on that stage, and the C.O.s or nobody couldn’t do nothing. So it was my freedom that Prison Performing Arts gave me when I was locked up.”

“Freedom of expression?” Limber interjects.

“Freedom of expression, freedom to…you know, in chow hall I might not say nothing to you, but we got rehearsal, soon as we come in, we brothers.”

Jones says PPA changed him. “You build a new person when you let all your bricks and walls fall down,” he says. In building himself back up again, PPA was “that first brick—that first cement poured into the basement to set the foundation. That’s what it was for me. I gotta keep it there to keep me on an even keel.”

One of the key perks of the alumni troupe: It pays. “It’s really hard to get a job with a prison record,” concedes fellow PPA alum Julie Antonic. “Before I even left Vandalia, Chris offered me a job, a paying job. It was the day after I got out of prison in March that I started working for them. And this is one of my strongest support systems.” She remembers getting kicked out of the place where she was living, when a fellow alumni troupe member happened to call her. When she told him what happened, he said he’d come pick her up in an hour and she could stay with him till she figured things out.

The alumni company doesn’t have a regular season or venue, but they perform at festivals and do command performances around town. Recently several players went to other theatre companies to consult when those companies staged plays either about or set in prison.

As rehearsal continues, everyone is certain they’ll have it together for the performance tomorrow. “We come alive in front of an audience,” says Antonic. “And especially this audience.”

Unlike Hogan Street, St. Louis City Juvenile Detention Center, where minors accused of a crime await adjudication, feels like an institution. The halls are gloomy and the kids wear sweat suits, the women in yellow, the young men in either green or brown pants and black shirts. Staff members have a ring of keys to get around. There are murals to cheer the place up—a pair of African American hands clasped in prayer, kids dancing—alongside inspirational posters with words like “success” and “imagination” on them.

It’s a Tuesday evening and the center’s 20 or so inmates gather in the cafeteria for the show, part of PPA’s Arts Alive! program, which brings in theatre from around St. Louis (PPA’s other programs include Learning Through the Arts and the Hip Hop Poetry Project). Tibbetts asks the kids if any have heard of Shakespeare. About half raise their hands; fewer raise their hands when asked if they’ve heard of Midsummer. Tibbetts explains the premise briefly, then the alumni company takes over.

Despite the Shakespearean language and the audience’s lack of familiarity with the material, the show is a hit. Kids laugh riotously at Scott Brown’s Thisbe and Antonio Brison’s Bottom as he transforms into an ass. The biggest hit of all is Chambers’s lion, whose roar somehow elicits a laugh every time he does it. Several of the teens offer the group a standing ovation.

“They were a great audience,” Antonic says. But what she was most looking forward to was the Q&A afterwards: “It was a special setting because we really wanted to reach out to them.”

“How y’all remember all this stuff?” asks one of the kids. “Sometimes we don’t!” Antonic jokes. Another asks skeptically, “All six of y’all was in prison?” The other kids in the audience laugh.

“I was incarcerated for 19 years for second-degree murder,” says Tracy White. The kids get quiet. “I didn’t want to leave the same way I came in.” She explains that she joined the Prison Performing arts program to get out some of her anger and frustration.

White was angry about her mistakes and about being apart from her children. “Prison is not fun at all,” she says. “You don’t want to be in there for long like I was. Being a mother from jail is hard. You can’t hold them like you want to. You can’t talk to them like you want to.” She starts to cry and a girl in the audience starts to cry too.

“This is not the deciding moment of y’all’s lives,” says Chambers. “Learn from it. Don’t be like me and wait till you get in trouble and then go right.” Other panelists echo Chambers, telling the kids there’s still time to change and a way forward. There’s a brief lull. Maybe the kids have heard this before. Maybe they hear it all the time and it goes in one ear and out the other.

Then a hand goes up. “How old do you have to be to be in the program?” one of the kids asks. Tibbetts explains that it is only for formerly incarcerated adults and he seems a bit disappointed. She later tells me the same kid was so intrigued by the show that he’s started reading Shakespeare’s Henry V.

Tibbetts herself almost starts to cry as she wraps up the evening. “It was just so special, because it was these two groups that I work with on a pretty regular basis and everybody just really allowed themselves to be vulnerable,” she tells me afterward. “I have rarely seen that kind of reaction, where the young people just allow themselves emotionally to kind of unfold in the moment. There was something really important about being in the room with everyone.”

For the actors it was just as meaningful. “That was actually one of those times you can say you gave something back to society and tried to make it better in whatever way you thought you could,” says Jones. “I’d like to say I got more out of it, just being able to do that.”

Back at Hogan Street it’s the big day of The Grinch performance. Since the stage in the gymnasium is used to store old treadmills and weight benches, gym mats, and tables, the curtain has been closed and students act on the lip of the stage. All the teams are assembled, sitting in separate groups. There is a dull rumble of conversation that quiets down, for the most part, during the show.

Each of the groups takes the stage for a humorous and smooth production, though not a flawless one. The young men clearly have fun, and when it’s all over, they listen to an inspirational talk from Mynista, a religious rapper who talks about his mother being a crack addict and going to prison himself on three armed robbery charges. He also talks about worshiping Satan (not figuratively), then finding God. It’s hard to know exactly what the young men at Hogan get out of this. They exchange looks and laugh, but when he asks if any of them want to rap freestyle a bunch of them eagerly volunteer.

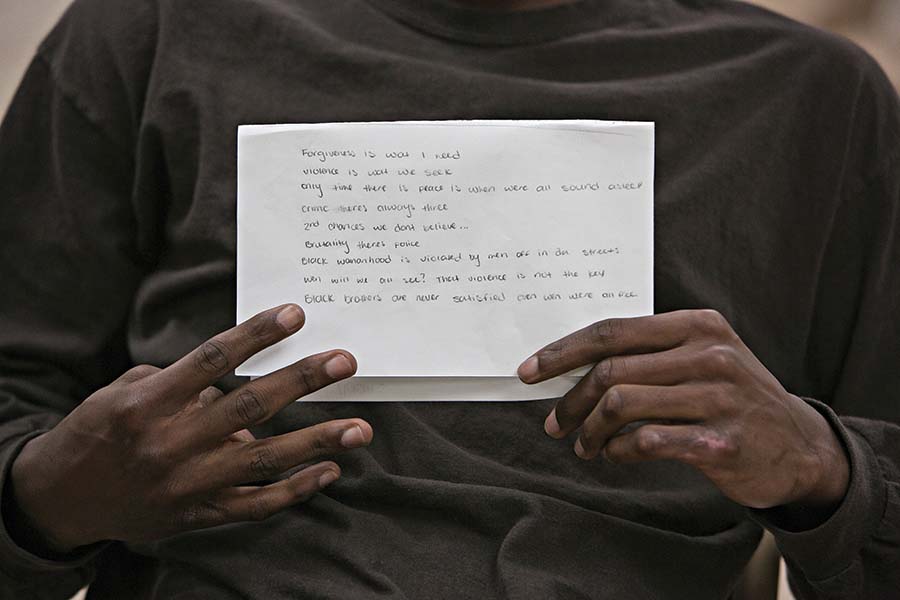

One of the young men freestyles while still wearing his Grinch hat, rapping about guns, violence, and how all of the good police seem to be in white neighborhoods. Mynista plays his own song, “Selfie.” He gestures for one of the young men to get up and the boy obliges with an energetic shoot dance.

Soon half the other young men are up with him bopping around the gym. They don’t seem to have a care in the world, and maybe, in this moment, they don’t.

Rosalind Early is the associate editor of the alumni magazine for Washington University in St. Louis and a freelance theatre critic for St. Louis Magazine.

*The names of current inmates have been changed.