Iranian playwright Nassim Soleimanpour did not arrive in New York to star in his new play, Nassim, until 8 p.m. on Dec. 5, the day before first preview. That’s because it took around eight months, and a letter from Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, to convince U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services to give a visa to an artist from one of the countries on President Trump’s travel ban. To Soleimanpour, the worst thing about the experience wasn’t the meeting with lawyers or the thousands of pages worth of paperwork. It was the uncertainty.

“Theatre does not work like, you get your visa today and you arrive tomorrow,” he explains. “You have to know [in advance] because you want to announce. And with our show, you want to cast.” He hails the show’s producers, Barrow Street Theatricals, as “very brave…I’m very proud of them.”

This is Soleimanpour’s first time in America, which is astounding when one considers that his previous play, White Rabbit Red Rabbit, has played in 29 cities Stateside (including a 2016 Off Broadway 42-week run starring such actors as Whoopi Goldberg and Nathan Lane). That play’s structure is atypical: It requires no set and no rehearsal; a different actor every night arrives and reads the script cold (with varyingly disarming results). Since the show’s premiere in 2011, it has been performed at almost 300 venues around the world and in a dozen languages.

For Nassim, the playwright was determined to shake up the format that he pioneered to great theatrical effect in his previous play. For one, when Soleimanpour first wrote White Rabbit Red Rabbit, he couldn’t leave Iran; the government would not give him a passport unless he completed two years of military service, which he refused to do. Then in 2012, Soleimanpour was diagnosed with an eye disorder which exempted him from military service.

So now, passport in hand, Soleimanpour was determined to “meet all those brave people who did Rabbit—we’re talking about 2,000, 3,000 people,” and also make some new friends along the way.

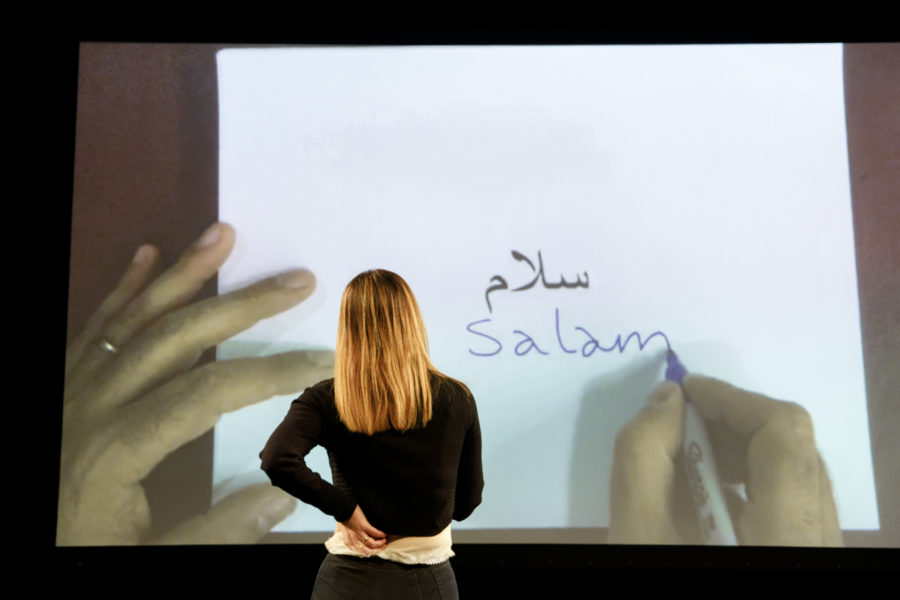

Nassim places Soleimanpour onstage with a new actor every night, who—as in White Rabbit Red Rabbit—cold-reads from a script, reacting in real time to challenges set by the playwright. Soleimanpour does not speak onstage; instead he merely flips the pages of the script for the actor, and will sometimes react to what’s happening by marking up the pages. Among other things Nassim is a kind of cultural exchange, where the performer, the audience, and Soleimanpour learn words from each other’s languages.

Though Nassim is performed in English in New York—and Soleimanpour is fluent in English, Farsi, and German—according to the playwright, it becomes a real challenge when he performs the show in a language he doesn’t know. Since January of last year, Soleimanpour has been touring the play around the world. Prior to going to a new country, Soleimanpour will have the script translated into the host country’s language (so the actors can read it). Nassim has been performed in a dozen languages. It doesn’t mean Soleimanpour is fluent in all of them. “Sometimes you feel totally stupid, they’re talking to you and laughing and you’re like, ‘I don’t know what you’re saying,’” he says, chuckling. “It’s very nice to do another language.”

Nassim will play through April 20 at New York City Center; actors including Tracy Letts and Michael Shannon have costarred so far, with actors such as Kathy Najimy, Jessica Hecht, and Michael Cerveris slated for the future.

I spoke to Soleimanpour this week about how he came up with his unique structure, and why he always knew White Rabbit Red Rabbit would become a worldwide sensation.

DIEP TRAN: What has been the most memorable word you’ve learned so far?

NASSIM SOLEIMANPOUR: I remember the first time that I heard “fuckwad,” it was funny to me. Because I’ve never heard of it. Every night is really fun.

When you perform the show in non-English-speaking countries, how are you able to follow along in a language you don’t know?

The first thing I have to know is where we are, when do I flip a page? If I know it visually I will be fine with some pages. Secondly, there are things I have to write, so then you have to memorize it. Every night you get a new performer. In Seoul, for instance, if you do it for 27 nights, you have to learn 27 names in Hangul, because I have to write their name during the show. And every brave actor and audience, since they are kind enough to learn some of my language, it’s respectful that I try and I learn at least their names in their language. So then you memorize and you practice and you practice.

I remember show seven or eight in Seoul, they were showing photos of their family to me, the actors, and I was putting a question mark, “What’s their name?” The person would respond, and I started writing it down on the spot, and the whole room was like, “ahh,” and I was like, “Ahhh, I’m writing in Hangul!”

What inspired you to write in the form that you do?

My dad is a novelist; all my uncles are known Iranian writers. So most of the good ideas were spoiled by the time I started to write. So very immediately, I came up with this urge that it should be surprising.

And then I think it all came out of a necessity, this cold reading format that is White Rabbit Red Rabbit. I was obsessed with freshness and authenticity, which doesn’t have any rehearsal. Like this [gestures to the two of us], we didn’t rehearse, we do it only once.

And I don’t want to repeat [White Rabbit Red Rabbit]. And I think [Nassim] is the same basics, but I try to take it to the next level. Is there anything else to explore? Maybe I’m so stubborn that I would plan to go to different countries, teach them my mother tongue and learn their language. And I’m not saying it’s very valuable but probably, hopefully unique.

So when you sit down with a blank page, do you think of form first?

Yeah. And it’s funny. Right now I’m writing a play for Audible. It has a story and I’m trying to be concentrated on the story and not on the form. Because I think this is a paradigm shift for me. It’s really weird. Normally it’s the form. I know where it starts, I find every brick, I plan everything, so then I start executing. And then you execute and you see that it doesn’t work, and you go back. That’s why Rabbit was 7 years [to workshop], BLANK was five, this was three and a half.

Would Nassim work without you?

I think it will. Structurally, you can get a French actor, you can call the show after them. You can go to Italy, teach Italians French, the whole play would work.

But right now that’s not the decision, because the touring is going quite well, and we already have things in our calendar for the next year, and also 2021 and 2022. There are countries and cities I haven’t visited.

When you wrote White Rabbit Red Rabbit, did you think it would be done around the world?

Yes, yes, yes.

Oh wow. How?

Because it was designed to do it. Sometimes I think I disappoint people that I’m not the poor Iranian who luckily did something. That is not the case. You cannot wake up in the morning and suddenly you’ve designed a good car which goes very fast. You have to have plans and you have to execute them. And you have to have lots of trial and error. I did my trial and error; you didn’t see them because I was in Iran.

I knew it didn’t have any cargo so it’s very easy to put it on, the show can basically be performed simultaneously in many countries, which has happened many times, and it’s still happening now. In one night we’re in seven countries. That’s not common for a show.

And marketing-wise at the time I didn’t have anyone helping me, so I put my email address in the show. I urged people to write to me. I asked a random audience member to keep the script after the show; it’s my way of spreading the word. It was a strategy and it worked.

Since theatremakers read this magazine, I’m sure they would love to know, when you first sent it out, who did you send it to?

Okay, that’s a very good question. You have to know that I’m in Iran, the play is written in English, it’s not to be performed in Iran. But I don’t have a clue. I know you have Broadway, but I don’t know anything, I don’t know anyone. What I do is, I still remember that day, I put a map on my desk. And I’m like, where do you want to do the show? And I pick three cities: New York, London, and Paris.

First I sent it to the Brick Theater in Brooklyn. I told them the premise: You don’t need anything, you don’t need rehearsals, you don’t need me. And they were doing something about the Middle East and Iran, and that was a good match. They put it on [in 2011]. My Canadian friend [director Daniel Brooks] came to watch the show. He falls in love with the show, and he works with me as a dramaturg and we work on it simultaneously for Edinburgh [Festival Fringe] and Toronto Summerworks, and it becomes a hit.

So what you learn is: no excuses, just write and try to pass it to good people to read, and if they’re not interested, put it in your drawer, write the next one. You’re a writer, you’re not a complainer. You have to write.

And now the entire world is your audience.

I think the entire world belongs to all of us. I understand borders have been there for protection, but I think we can pass this phase—we are not dangerous to each other, we don’t need borders. Why would I spend eight months and hundreds—the amount of pages our show has is 400-500 pages. I bet we spent three, four times more pages to get me into the country. I could use that time to write another two plays, or the producers can produce two more shows. So I think we should be past this stuff. And then there’s no China or Japan or New York. These bubbles are wrong. I think any writer, any artist knows this.