Nancy L. Donahue has a passion for the town she grew up in, Lowell, Mass., and for good reason. The small city (pop. 100,000-plus) north of Boston, which dates to 1826, figured prominently in the American Industrial Revolution, thanks to its abundant textile mills and factories. Today many of its historic manufacturing sites have been repurposed or preserved by the National Park Service, and visitors come to pay homage to cultural figures connected to the town, like painter James McNeill Whistler and Beat icon Jack Kerouac.

Lowell is also home to an active LORT professional theatre, Merrimack Repertory Theatre, in whose 1978 founding Donahue played a crucial role. It’s a role she hasn’t left since—indeed, she has been a force in the theatre’s day-to-day operations throughout its 40-year history.

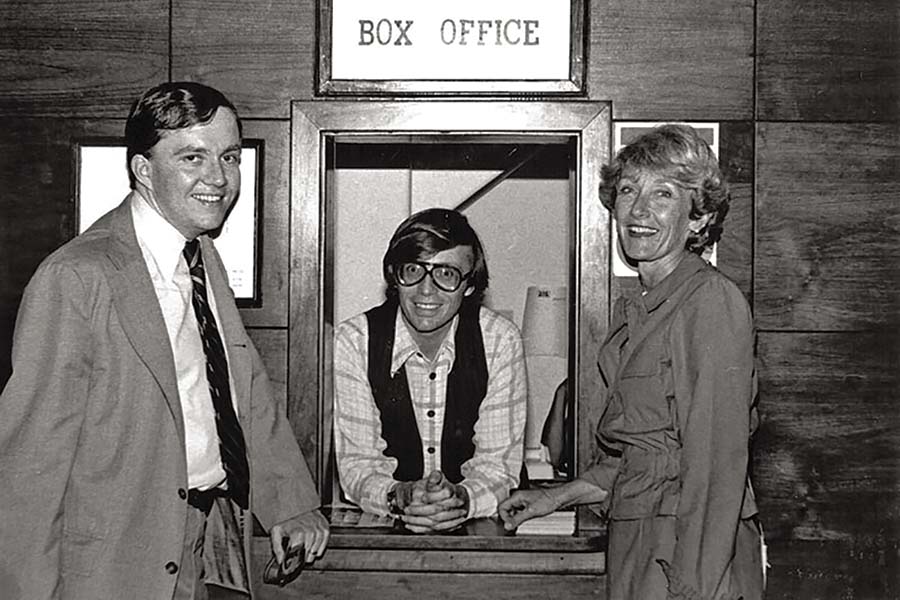

Now 87 and the mother of 11 children—including internationally known fashion model, entrepreneur, and health-and-fitness guru Nancy C. Donahue—she was enlisted in the Merrimack cause when a hometown colleague, Barbara Abrahamian, introduced her to its organizers, a pair of young theatremakers named Mark Kaufman and John Briggs. Fresh from jobs in summer stock in Salem, N.H., Kaufman and Briggs shared their hopes and plans with Donahue, then working at the newly opened University of Massachusetts-Lowell, where she was helping university president John Duff raise funds to bring world-class culture to Lowell. It was an instant fit: Duff was able to provide the foundling company with its first space, UMass Lowell’s Mahoney Hall. And multi-tasker Donahue—willing to steal time from the tennis court, where she was the city’s reigning doubles champion—eagerly embraced the role of board president for the new venture. MRT was born. In subsequent decades Donahue would reprise the role of MRT president six times, and in 1992 she began serving as board chair, a role she still retains.

The going was tough early on. In the ’70s, Lowell was best known for hosting the New England Golden Gloves boxing championship; the Whistler Museum housed a wonderful collection, but it was, as Donahue puts it, “a dusty place, and the board meetings were tea parties.” The wife of noted lawyer Richard K. Donahue, also a philanthropist, she yearned to offer Lowell’s citizens more vibrant, sophisticated cultural offerings, including top-flight theatre.

Fortunately the federal government was simultaneously in the process of opening an urban national park on the site of the old textile mills in Lowell. As Briggs recalls, “The feds already did all the work—we knew that people were willing to travel to Lowell for culture.”

As MRT’s newly appointed president, Donahue gathered her friends and neighbors and began to raise money, although, she recalls, “The people of Lowell were not in the habit of giving. We began as an Equity theatre, and people were shocked at the price tag.” According to Briggs, Donahue held more than 150 teas and brunches with up to 40 people at each. “We sold 2,000 subscriptions without even printing a brochure,” he avows.

Donahue was willing to play hardball. Founding co-artistic director Briggs remembers their visits to the 13 banks in Lowell, where Donahue called upon the financial institutions to do their civic duty. “We walked into a bank in Lowell, very conservative, all granite and marble,” says Briggs. “Nancy pulled out her checkbook, wrote out a check and pushed it across the table, and said, ‘I expect you to match that. And I expect you to get the other banks to follow suit.’ And they did.” Each of the founders, including Abrahamian, credits Donahue with the success of the theatre. According to Briggs, “She understood what building this theatre would mean in the long run.”

Not that there weren’t some growing pains. “The first year we were bleeding money, and the board panicked,” says co-a.d. Kaufman. He and Briggs had originally flipped a coin to determine who would be the managing and who the artistic director: Briggs drew managing director, but left after a year. At the end of MRT’s third season, Kaufman left as well, citing differences with the board over what to produce. Donahue and Kaufman both remember it as an extremely painful time.

The press was not always kind, either. After the theatre moved from the UMass campus to a well-appointed downtown location, Liberty Hall, in 1983, Donahue remembers a local newspaper running a cartoon of her wearing a tutu in a boxing ring with the caption, “Is Mrs. Donahue happy now?” The cartoon suggested that theatre and boxing don’t belong in the same neighborhood. Donahue dismisses it now with a laugh as “absurd.”

At the same time the theatre was being developed, what became known as the “Massachusetts Miracle” was also taking shape—tech companies began to move into the region, and Wang Laboratories came to Lowell in 1976. The theatre thrived in the ’80s, but as the tech industry subsequently retreated to other parts of the country (Wang left in 1997), the economy of the area floundered, and MRT came very close to shuttering. Charles Towers, who had assumed artistic directorship, was responsible for the “keep live theatre alive” campaign that raised enough money to keep the theatre open. Towers, Donahue says, was a stabilizing force, “very organized, very particular, and very straight-down-the-line. He brought the theatre to a different level and stretched the audiences.”

If, during the ups and downs of the company’s history, Donahue asked herself many times, “Why am I doing this?”, the fact is that her commitment never truly flagged. She has always maintained a close relationship with the theatre’s staff and has been a part of the hiring of every artistic and managing director since the founding of the theatre.

It is unusual for a city the size of Lowell to have a theatre with the budget size and reputation of Merrimack Rep. “MRT says a lot about Lowell,” Donahue reasons. “Lowell is a typical blue-collar city, a gateway city, a place for immigrants to come and grow and thrive. To have this theatre as a part of all that is very important, I think.” She is referring to immigrants who first came to Lowell during the early 19th century to work in textile mills, many of whom—including the ancestors of Donahue’s husband, Richard, who died in 2015 at 88—thrived. Much later, in the 1970s, Cambodian refugees found a home in Lowell, and now make up 13 percent of the population.

According to Jeffrey Thielman, president and chief executive of the International Institute of New England, the city “has been replenished and reenergized by refugees and immigrants for generations.” For her part, Donahue remains devoted to the vibrant, diverse community. Current MRT artistic director Sean Daniels call her “unlike any other donor I have ever known. On Saturday mornings she picks up trash on the riverbank. That’s how you make a great community.” Daniels adds that she possesses “a level of generosity we should all aspire to.”

What makes a person like Donahue tick—why has a successful, multifaceted professional devoted so much time to improving her community and its theatre? “I am so blessed,” she effuses. “Neither I nor my kids have needs like so many do. I wish everyone understood the joy I take in this work.” She quotes Maya Angelou: “‘Giving liberates the soul of the giver.’ I love to do it. I feel lucky.”

Deb Clapp is the executive director of the League of Chicago Theatres.

An earlier version of this story mistakenly attributed a few quotes from John Briggs to John Duff, who died in 2013.